쉔팅쳉 아키텍츠_ 쉔

틴 쳉

대만 4세대 건축가의 특질

쉔 팅 쳉은 대만 자이 시 출신으로, 타이베이에 기반을 둔 쉔 팅

쳉 아키텍츠를 설립했다. 건축, 환경, 자연의 관계를 재해석하는 것을 바탕으로 건축물 각각의 역할에 적합한 형태를 찾고, 시적이고 새로운 공간을 설계하고자 한다. 대표 프로젝트로는 라이트

하우스(2016), 플로팅 파빌리온(2016), 자이 기차역

광장 리노베이션(2017), 시지안대학교 건물B(2018) 등이

있다.

쉔 팅 쳉(쉔): 대만의 현대건축은 일제 식민지기인 제2차 세계대전 이전에 시작되었다. 1930~1945년 즈음 일본은 기차역, 철도, 전매청, 설탕 정제소와 같은 기반시설을 대량으로 건설하면서 콘크리트, 강철을 이용한 건설 기술을 도입했다. 전후 대만은 정부의 영향으로 중국적 특징을 가진 건축을 장려하는 문화적 르네상스를 겪었지만 서양 모더니즘의 아이디어도 동시에 꽃피기 시작해 건축에서 두 개념이 역설적으로 충돌하면서 독립적으로 존재했다. 1970~1990년대는 급속한 도시화의 시대였다. 지역 산업과 부동산의 부상으로 도시가 고밀도화, 현대화됐다. 1990년대 말, 사회가 전반적으로 자유화되고 정치적 이념이 중국에서 멀어지면서 풀뿌리 운동이 서서히 추진력을 얻었다. 건축가들은 기능에 초점을 맞춰 대만에 적합한 건축물을 설계했고 이후 몇 년에 걸쳐 다양한 지역 건축이 촉발됐다. 2010년 이후 다양한 하위문화와 온라인 미디어가 등장했고, 이는 건축의 경계에 영향을 미쳤다. 미술, 설치, 전시 등이 건축의 디자인 요소로 거듭났고, 건축적 사고는 지역에 국한되지 않고 보다 기본적이고 단순하며 순수한 개념으로 변모하는 과정을 거치고 있다.

쉔: 1세대 대만 건축가들은 1915~1935년에 중국에서 태어나 서구 모더니즘 건축 교육을 받았고 그들의 건축은 주로 자국의 근대화에 대한 논의로 이루어졌다. 이 시기에 두각을 나타낸 건축가로는 대만 모더니즘 건축의 선구자 중 한 명인 왕 다 홍(1917~2018), 대만 퉁하이대학교 캠퍼스와 루스 기념 채플을 설계한 건축가이자 예술가이자 교육자인 천 치 콴(1921~2007)이 있다. 2세대 건축가는 1935~1955년에 태어난 건축가들로, 경제가 발전하기 시작하고 부동산 개발이 부흥하는 등 빠르게 발전하는 대만을 목격하며 자란 세대다. 그들은 문화, 상업, 건설 기술, 모더니즘, 포스트모더니즘의 건축적 영향을 허물기 위해 노력했다. 이 시대의 대표적인 건축가는 대만의 랜드마크인 타이베이 101을 설계한 추 유안 리(1938~), 신추고속철도와 란양박물관을 설계한 크리스 야오(1951~)가 있다. 이어서 1955~1975년에 태어난 3세대가 등장하는데, 당시는 사회정치적 분위기가 자유화되고 사람들이 민주주의를 향하던 시기였다. 시대상에 맞게 건축도 사람, 땅, 환경에서 영감을 얻은 지역 건축이 시작됐고 보다 열려 있고 대중과 소통하는 건축이 등장했으며 쉥-유안 황과 제이 추가 그러한 건축을 했다. 마지막으로 4세대는 1975~1985년에 태어났는데, 개인적으로 이 세대의 건축가들은 이전 세대가 환경을 대하는 태도에 영향을 받은 것 같다. 그러나 지역에 영향을 받는 경향은 줄어들어 세계를 그 자체로 받아들이는 듯하다. 표준화, 세계화, 자본주의와 같은 주제에 맞서고 있는데 아마도 현대미술과 건축 이념의 부활, 소규모 건축이 그들에게 영향을 미쳤을 것이다. 이들은 내재적인 표현, 사람의 감각과 건축과의 상호작용, 작품이 아닌 건축을 하려는 시도를 하고 있다.

쉔: 건축을 문화에서 독립시킬 순 없지만, 문화적 가치만을 표현하려는 건축은 지나치게 경직된다. 대만 문화의 가치를 정의하기란 참 어렵다. 대만 사람들만의 독특한 생활방식이 있고, 지금도 모든 분야가 저마다의 가능성과 가치를 탐구하고 있으며, 대만 문화의 재발견과 재건의 시기를 맞고 있는 현재로서는 건축가가 확신을 가질 수 있는 단일한 문화적 영감은 존재하지 않는다. 우리는 더 이상 문화를 표현하는 것을 열망하지 않는다. 오히려 개인적 경험에 집중하면서 저마다 새로운 것을 지속적으로 시도하고 있다.

쉔: 건축은 때때로 뜻하지 않게 사람들의 삶의 질을 방해하기도 한다. 그렇기 때문에 나는 건축을 일종의 촉매로 생각하려고 한다. 임시적이든 영구적이든, 촉매로서의 건축에 있어서 핵심 아이디어는 동일하다. 가령 건물의 배치를 통해 더 활기찬 일상을 이끌어내거나 때로는 사람들에게 변화를 경험하게 하는 등의 영향을 고려한다. 하지만 이러한 종류의 건축이 삶의 짧은 순간만을 사로잡으려는, 장식적으로 접근하는 태도에는 반대한다. 기존 환경과 공존하고, 기대고, 충돌하며 새롭고 근본적인 삶의 흐름을 만드는 건축을 하고 싶다.

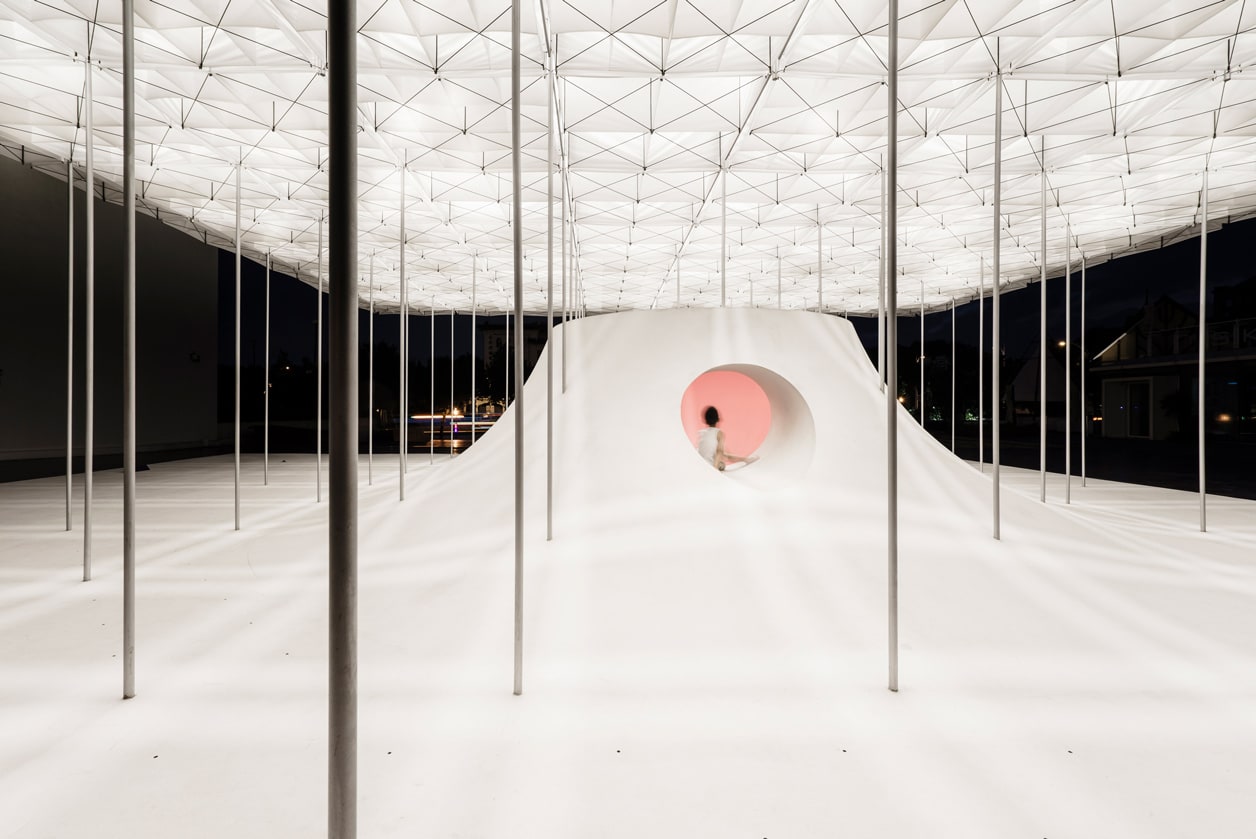

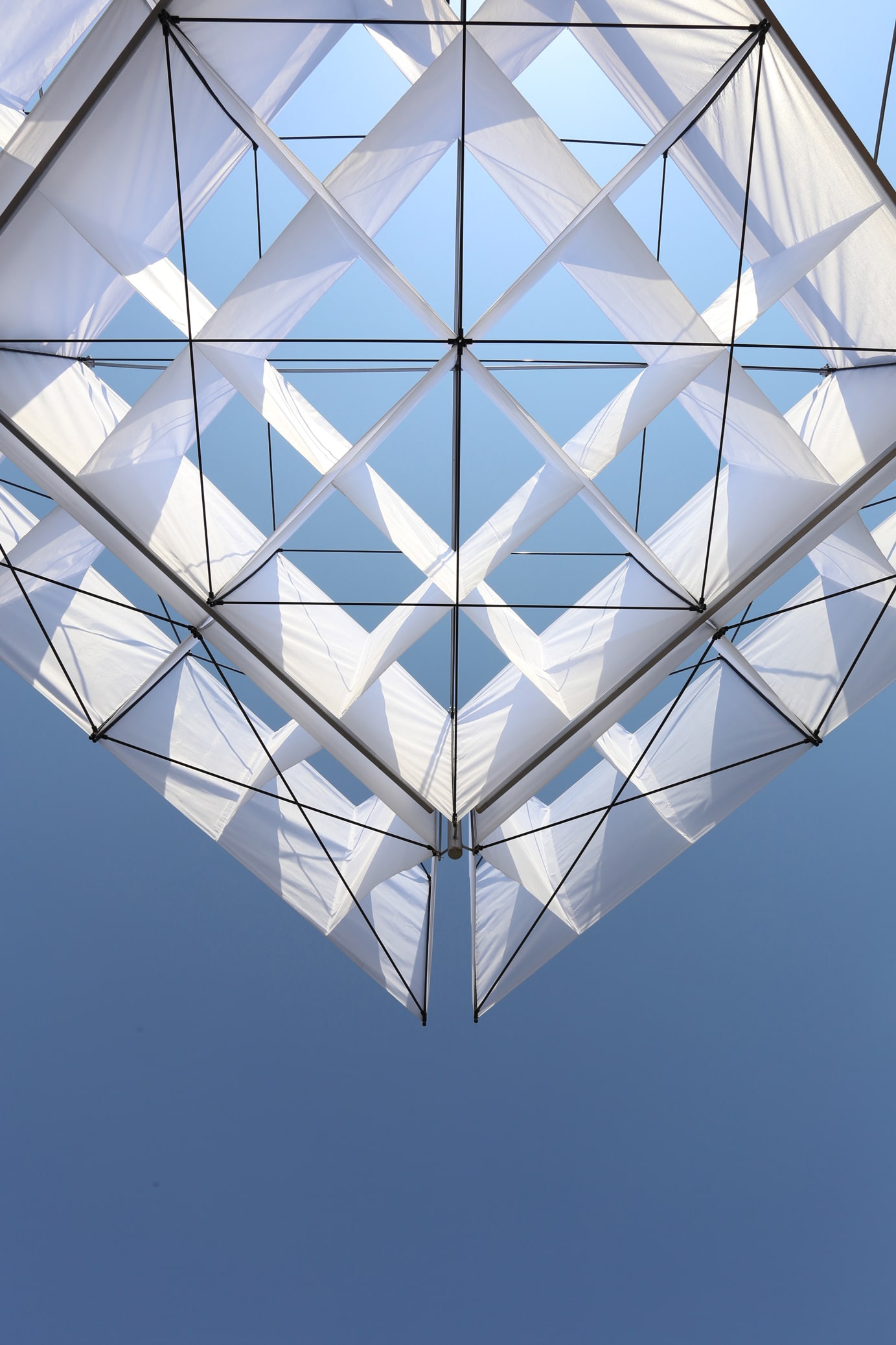

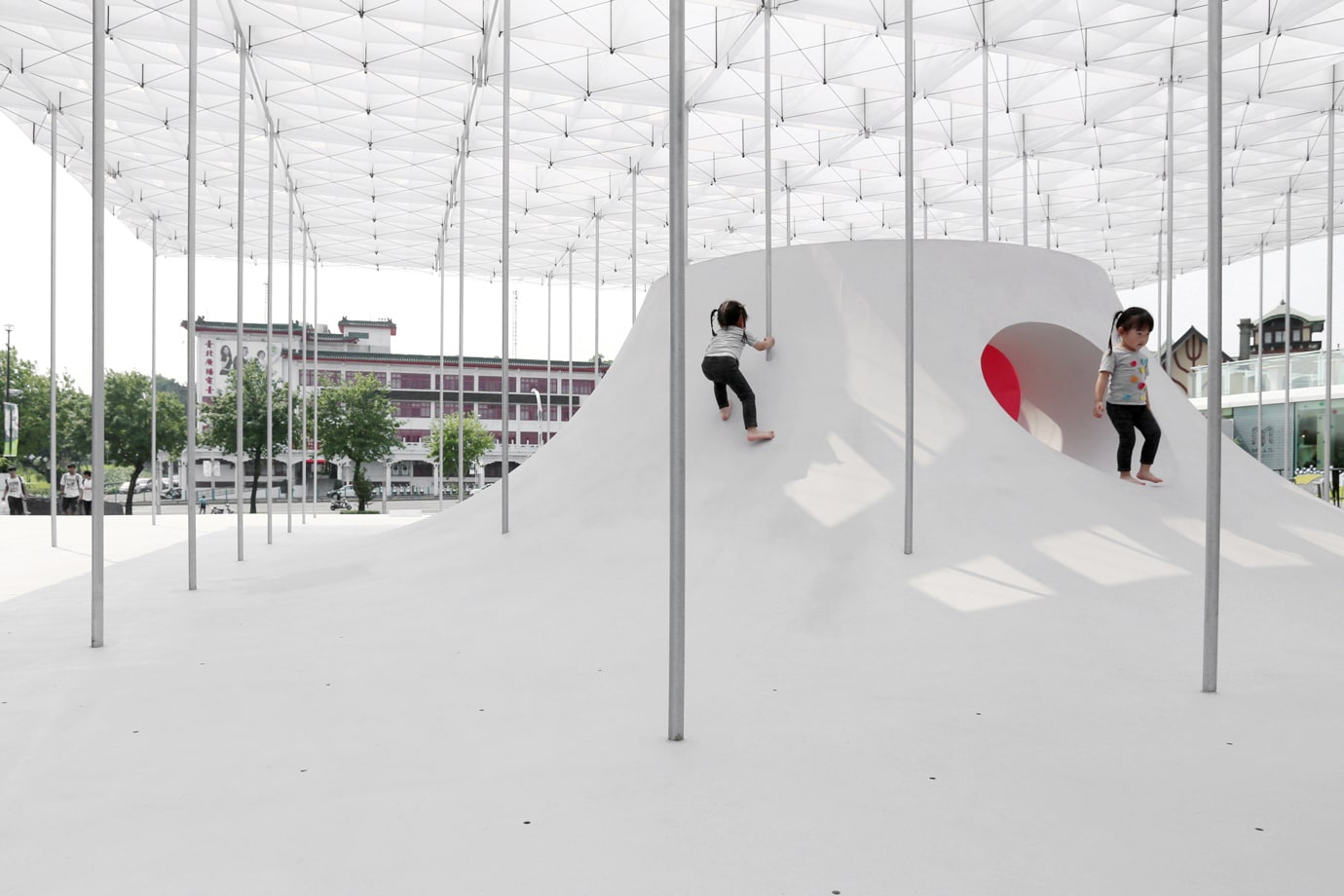

쉔: 광장은 바람과 햇빛이 강해서 사람들이 이곳의 공간을 온전히 느끼기에는 어려움이 있었다. 이 극한의 자연을 포착하는 반투명한 연으로 플로팅 파빌리온을 설계하여 사람들이 충분히 이곳을 경험하고 기억하도록 했다. 사람들은 파빌리온의 독특한 느낌에 매료되어 공간에 애착을 가지게 되는데, 이는 파빌리온의 장소감에 큰 영향을 미친다. 더불어 임시 건축물로서 약하고 불안정한 성향이 있는데, 이는 건물과 자연의 연결을 더욱 긴밀하게 해 바람, 빛 등의 자연 요소가 파빌리온 안에 존재하게 한다. 불안정한 건축적 요소가 자연적 요소와 만나면 인간에게 적합한 스케일로 부드러운 장을 형성한다.

쉔: 타이베이 파인 아트 뮤지엄의 건축적 요소에서 연관성을 만들고자 했다. 예를 들어 네모난 박스 연으로 만들어진 파빌리온의 그리드는 뮤지엄 로비의 그리드 보에 대한 응답이었다. 하지만 이 두 구조는 부모와 자식처럼 크고 작은 스케일로 서로의 거리를 유지했다. 파빌리온이 박람회의 회전목마처럼 독립적으로 떠 있기를 원했다.

쉔: 연은 바람으로 인해 그 형태가 결정된다. 유연성, 불안정성, 반투명성, 가벼움 등의 성질을 갖춘 연은 현장 조건과 강하게 연계된다. 나는 그림자와 함께 구조적 가벼움을 표현했다. 또한 연을 사용하기로 결정한 것은 개별적으로 분리된 스케일을 의식했기 때문이다. 3개월간의 설치가 끝난 후 파빌리온에 사용된 300개의 연은 어린이를 위한 장난감으로 개작됐다.

쉔: 파빌리온의 목적을 제한하지 않았다. 다만 규모를 가볍고 변환 가능하도록 계획했다. 이 프로젝트에 접근하는 사람들이 자유롭고 편안함을 느꼈으면 했다. 실제로 현장을 방문했을 때 부모와 자녀가 파빌리온에 앉아 바람을 느끼거나 담소를 나누거나 책을 읽는 모습을 봤다.

박: 캐노피 아래로

내려오는 섬을 닮은 곡선의 볼륨은 사람들의 행동을 유도하는 성격도 띠는 듯 보인다. 그리고 곡면으로

인해 내부 소리의 환경에도 변화가 있을 것 같은데, 설계 의도가 궁금하다.

쉔: 나는 열린 공간을 계획할 때 항상 ‘활기찬 평화’를 가져오기 위해 교묘하게 수렴되는 무언가를 원한다. 곡선형 섬의 외부는 사람이 기댈 수 있는 공간을 제공하고 내부는 바람과 소리와 같은 자연 요소를 모은 그릇과 같다.

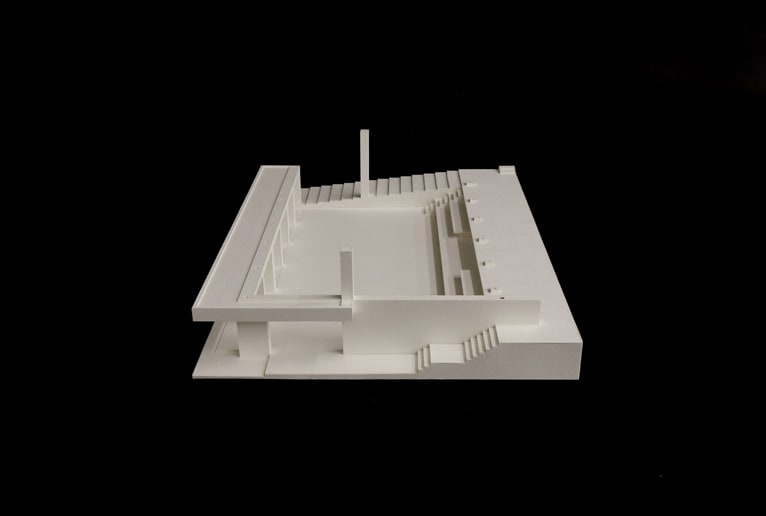

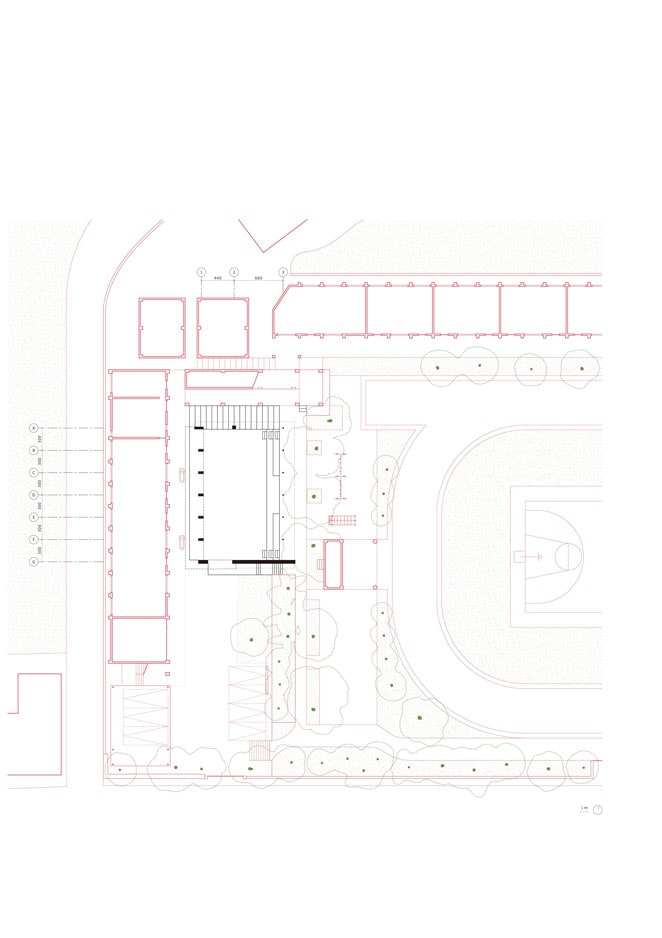

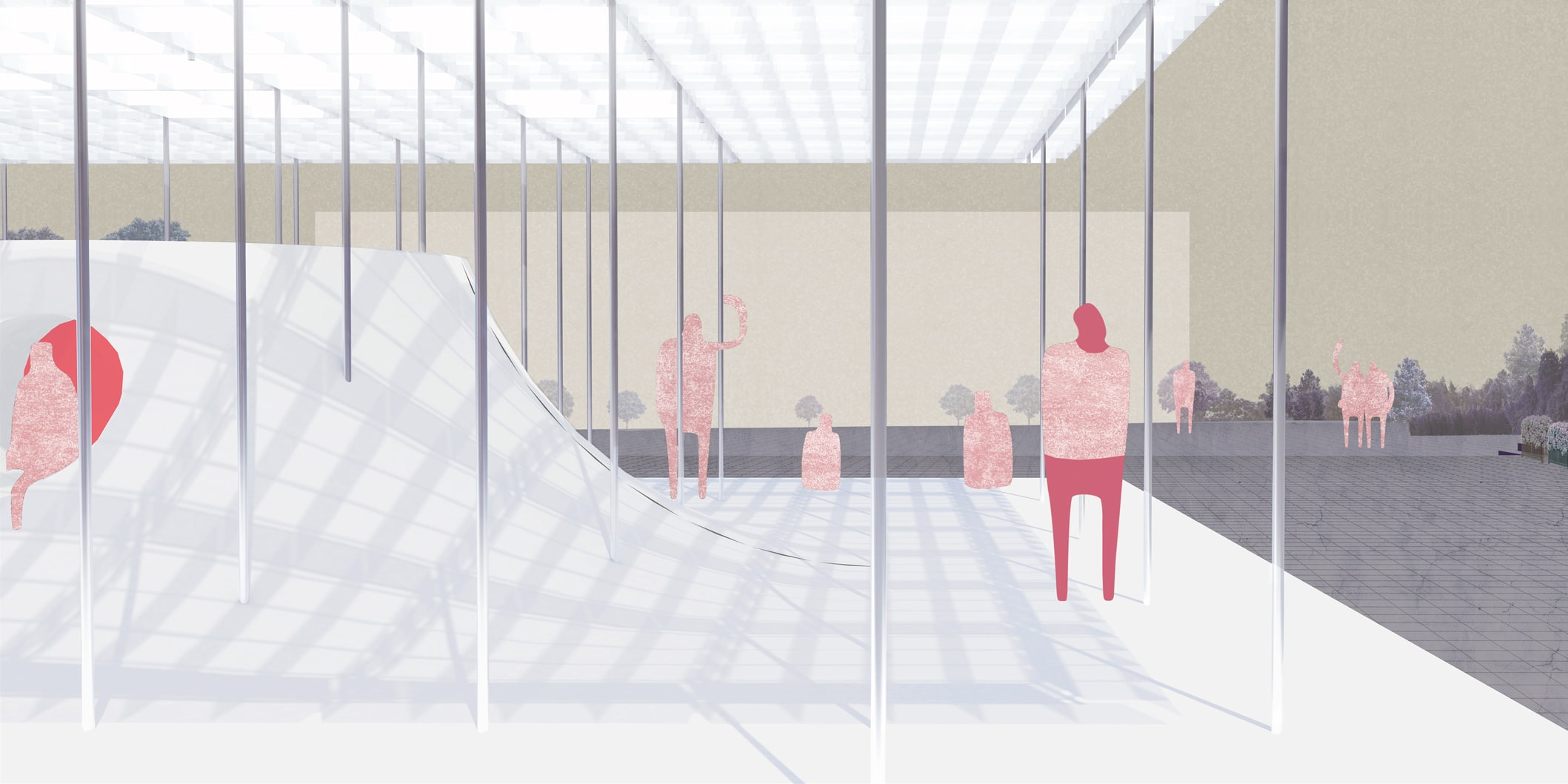

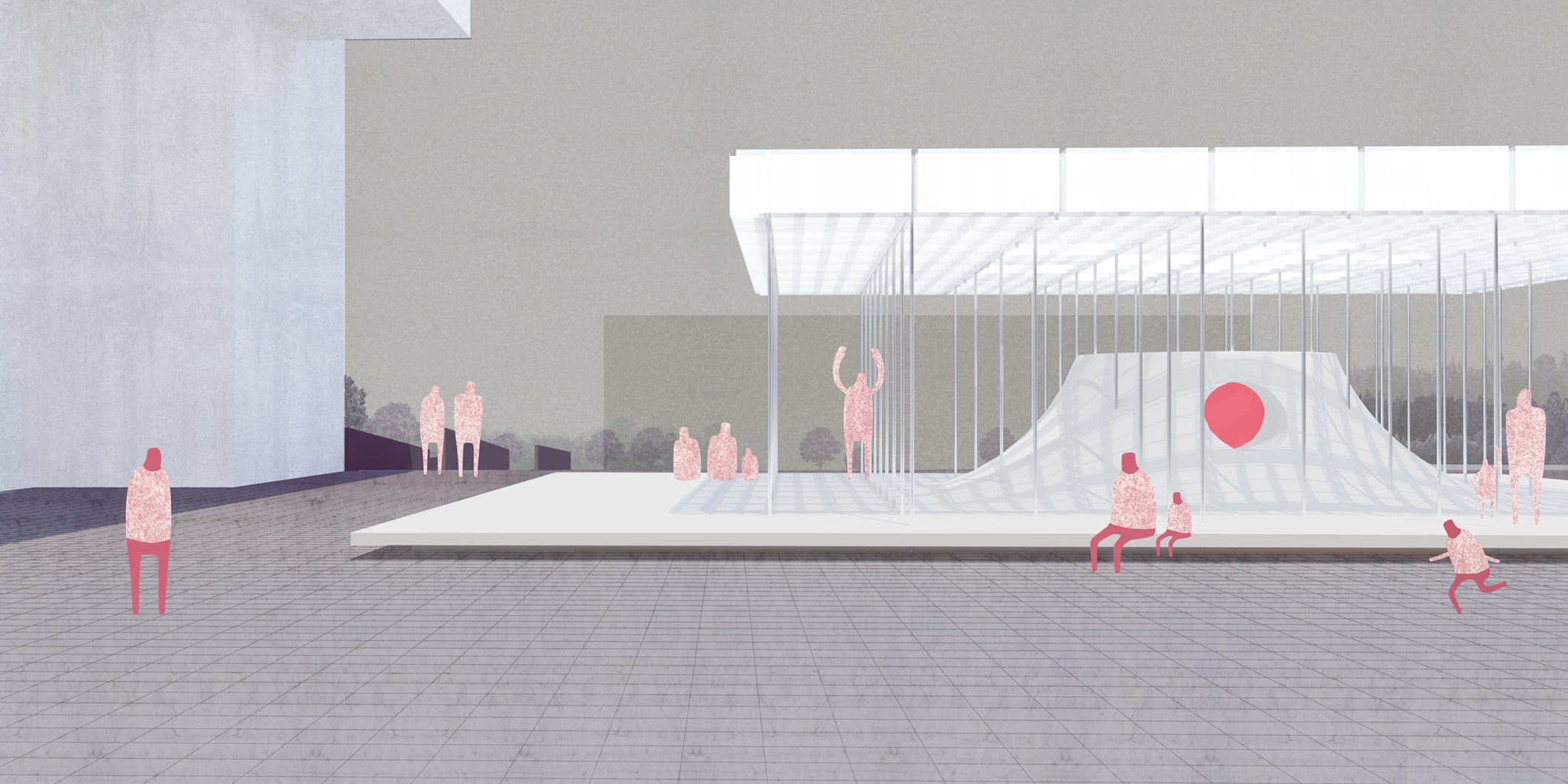

쉔: 현장에 있는 놀이터가 두 건물의 연결을 이끌어내는 원천이다. 포인시아나 나무와 놀이기구가 있어 아이들을 자연스럽게 놀이터로 끌어들이고, 이러한 자연스러운 놀이가 수업 시간뿐 아니라 쉬는 시간에도 이루어졌으면 했다. 내가 그렸던 건축의 이미지는 자유로운 형태를 가진 인공의 경계다. 기존에 있던 외부 요소들과 상호작용하면서 건물의 매스를 안정적으로 둘러싸는 그런 경계를 상상했다.

쉔: 건축은 내부 공간을 생성할 가능성이 크지만 동시에 외부 관계를 규제할 수 있는 무한한 잠재력을 지니고 있다. 내 생각에는 이 두 요소가 모순되지는 않지만 설계 과정에서 종종 모순에 직면하게 된다. 개인적으로 새로 들어선 이 활동 공간이 기존의 주변 질서를 재정립할 수 있는 특별한 조화로움을 갖기를 바란다. 새 건물이 기존 건물을 배제하거나 차단하지 않도록 경계하는 것이 중요하다. 따라서 배치를 계획하면서 디자인과 기존 건물 사이에 약간의 공간을 남겨놓았다. 그 거리는 미묘한 장력과 공간 사이의 전환을 만들기 위해 적절하게 남겨두어야 한다.

쉔: 기존 건물의 요소가 사람들의 ‘활동’을 장려한다면 그대로 유지한다. 심지어 강조하기도 한다. 반대로 새로운 결과물이 기존 ‘활동’의 흐름을 방해한다면, 그 요소는 없앤다. 또 다른 본질적 기준은 우리가 내부에서 보고자 하는 경관과 관련된다.

쉔: 이 디자인은 하나의 관점, 하나의 방향을 가리키지 않는다. 다양한 방향성을 가지는 구조로, 사람들이 그 사이를 돌아다니면서 점진적으로 새로운 공간을 발견하도록 설계했다. 기존 북측 경사면은 아이들이 놀기 좋은 공간이라 이 경사면에 어떻게 대응해야 할지 고민을 많이 했다. 결국 더 넓은 계단을 만들어 건물의 형태와 기둥을 연결하고 기존 경사를 확장하여 아이들이 새로운 공간과 기존 공간을 자유롭게 뛰어다니고 활동할 수 있도록 계획했다.

쉔: 남쪽 가장자리의 콘크리트 벽은 가장 먼저 나타나는 구조물이다. 초기 목적은 건축이 기존의 흙벽을 관통하여 대지의 힘을 받아들여 동서 방향을 연결하는 것이었다. 하지만 공교롭게도 내부에서는 주차장이 보이지 않아 결과적으로 산과 나무의 끝자락만 보이게 되었다.

쉔: 기존 회랑과 새로 지은 처마는 평면도에서 거의 겹치지만 단면적으로는 분리된다. 구조적 관점에서 지진이 발생해도 새 건물은 기존 건물에 영향을 미치지 않는다. 새 건물의 독립성은, 성격을 구분하며 여전히 서로의 소통을 유지하기에, 나에게는 중요한 의미가 있었다. 건물 전체를 강철로 지었다면 규모가 너무 크고 느닷없어 보였을 것이다. 그래서 재료의 전환이 대지와 혼합되도록, 건물과 환경을 연결하는 동시에 수평적 순환을 만들도록 했다. 또한 지붕은 기울어져 있어 공간의 방향을 시각적으로 알려주고 사람들이 나무와 공간의 관계를 인지하도록 유도한다.

쉔: 서쪽의 2층 복도에서 사람들이 활동 공간과 위층의 놀이터를 볼 수 있도록 하면 층 사이의 극적인 관계를 만들 수 있으며 공간을 유연하게 사용할 수 있다. 그러므로 전체 학교 운동장에서의 감각적 연결을 강조한다. 운동장에서 교실로 진입하는 과정의 연결성에서는 사람들이 건물에 들어가기 전 전환을 느끼는 것도 중요한 내용이었다. 또한 각 모서리의 디자인 요소는 기존 구조를 모방하여 공간과 건축의 언어를 연결하고 확장하려는 시도였다.

Shen Ting Tseng Architects_ Shen Ting Tseng

ON THE BORDER BETWEEN ART AND CAPITAL: SMALL PROJECTS

Shen Ting Tseng, born in Chiayi, Taiwan, is

the founder of Shen Ting Tseng Architects. The architecture firm is based in

Taipei, Taiwan. With the standpoint of reinterpreting the relationship between

architecture, the environment, and nature, the team pursues appropriate forms

for every role in each architecture and creates new spaces and living settings

that are authentically poetic. Representative projects include Light House

(2016), Floating Pavilion (2016), Renovation of Chiayi Railway Station Square (2017),

and Shih Chien University Building B (2018).

Shen Ting Tseng (Shen): Taiwanese modern architecture started before World War II, during the Japanese colonial rule. Between 1930 -1945, the Japanese introduced concrete and steel construction techniques while building vast infrastructural networks and facilities such as train stations, railways, the Monopoly Bureau, and sugar refineries. While post-war Taiwan experienced a renaissance in Chinese culture, in which the government encouraged the production of architecture with Chinese features, the idea of Western modernism had also begun to blossom simultaneously, resulting in clashes or independent occurrences of both concepts in architecture. 1970 -1990 was an era of rapid urbanization-with the rise of local businesses and real estate, cities developed a higher density and further modernization. At the end of the 1990s, as society had become more liberal as a whole and political ideologies had strayed from China, grassroots movements slowly gained momentum. Consequently, architects turned their focus to real living spaces, attempting to create designs suited to Taiwan, sparking a diverse regional architecture movement that would stretch out over the years. After 2010, Taiwanese culture has been probed wide and deep, creating a colorful array of subcultural and online media, which in turn has shifted the boundaries of architecture. Art, temporary installations, exhibitions, and more others have become elements in architectural designs, whereas architectural thinking has strayed from regional limitations and morphed into a more basic, simpler, purer version of what it once was.

Park: This is connected to history of

Korea, and the identity and interests of each generation follow the same

historical stream. What do Taiwanese young architects choose to focus on and

how is this focus changing?

Shen: The first generation of Taiwanese architects originated in 1915 - 1935, predominately born in China and educated in the Western world, so their architecture was a discussion of the modernization of Chinese architecture. The most significant architects during this era were Da-hong Wang and Chi-kwan Chen. The second generation of architects were born in 1935 -1955. They faced a rapidly developing Taiwan, when the economy was just taking off and cities grew with the development of real estate. As a result, they struggled to break through the boundaries of culture, business, construction techniques, modernism, and postmodernism. The representative architects are Chu-yuan Lee and Kris Yao. The third generation was born in 1955 -1975, when the political atmosphere became more liberal, and people worked towards a democratic society. At this moment, regional architecture movements drew inspiration from people, the land, and the environment, attempting to open architecture up to and encourage the public. The representative architects are Sheng-yuan Huang and Jay Chiu. The fourth generation were born in 1975 - 1985. In my opinion, this generation of architects were influenced by the former generation in terms of environmental thinking. However, regional influences were lessened as they accepted the world as a whole and fought against themes such as standardization, globalization, and capitalism. Perhaps it was modern art and the revival of architecture ideology, along with the privileging of architecture on a smaller scale that had the greatest impact on these architects, so they redirected their focus on internal expression and on sensory engagements with architecture, forming the basis of their attempts to return their labors to architecture.

Shen: Although architecture cannot be separated from culture, it becomes overly rigid when it is too eager to express cultural values. It is difficult for me to define the value of Taiwanese culture as people are still exploring the possibilities and values across every field, and even though people in Taiwan do have a unique lifestyle, Taiwanese culture is facing a time of rediscovery and reconstruction. For architects, a single reliable cultural source does not exist. We are retracing our steps to focus on individual experiences, no longer anxious to express our culture, but to continuously reflect and make new attempts.

Shen: Architecture sometimes accidentally obstructs living possibilities, so I like to think of architecture as a catalyst, deriving a livelier lifestyle from architectural assemblages, sometimes providing a chance for people to experience the exhilaration of change. Whether it is temporal or permanent event, the core idea of architecture as a catalyst is the same. However, this sort of architecture is often very noticeably decorated, like a cardiotonic that produces only an instant of life. I am against this approach; I want to create architecture that will coexist, depend upon, or even collide with its existing environment, creating a new but profound flow in life.

Shen: Due to the strong winds and scorching sunlight acting on the pavilion, people could not experience the space in an ordinary way. During the three-month exhibition of the Floating Pavilion, we tried to capture this extreme bout of weather through half-transparent kites, turning this experience into one that could be felt and remembered. Once enraptured by a unique feeling in a space, people get attached, and this plays a major part in the pavilion's sense of place. Temporal architecture tends to be more vulnerable and unstable, which further enables correspondence between the project and nature. On the outside, this pavilion may appear lackluster, but it is home to rich natural elements of wind and light. When unstable architectural elements are met with natural elements, together they form a soft field on a scale suitable for people.

Shen: I attempted to create continuity in the architectural elements of Team, for example the grid the box kites created was a response to the grid beams in the lobby. Though familiar, the two kept their distance, one large and one small, like a parent and a child. Perhaps I wanted the pavilion to float independently, like a carousel in a fair.

Park: It is interesting to use kites that

function only when there is wind, and I think it is a smart idea to create a

public place that acts as a shadow at the same time.

Shen: The box kites take flight due to the wind that blows through its dimensions; equipped with flexibility, instability, dimension, and a translucent, light appearance, the kite has a strong connection with the site conditions. It brings a lightness to the structure and creates playful shadows. In addition, the decision to use kites implies thinking on an individual scale, and after the exhibition, the three hundred kites that were used will become toys for children.

Shen: On site, we observed that there were parents and children, people that just sat there experiencing the wind, chatting, or reading. By not limiting the project to a clear purpose, and insisting upon a strict but persuasive scale, people that approach this project feel free and relaxed.

Shen: When planning open spaces, I always hope something will converge silently, calling forth a 'lively peace'. The outside of the curved island provides a space for people to lean on, while the interior is like a bowl that gathers natural elements like the wind and sound.

Shen: The playground on the site is a source of creating connections. There are poinciana trees and recreational equipment that naturally draws children into the playground, so I wanted to extend this natural playfulness to the new activity space, as it should not only be used during classes, but also during recess. To create the ideal connection with its surroundings, I had to imagine architecture as a freeform, plastic boundary, interacting with the existing exterior elements, the enclosing it within a stable architecture mass.

Shen: Architecture indeed possesses the ability to create inner space, but at the same time it harbors the infinite potential to regulate exterior relationships. In m>opinion, these two are not contradictory elements, and yet during the designing process we are often faced with contradictions. I do hope this activity space adopts a special orientation, which can also reestablish the existing surrounding order.

Shen: If the existing elements are encouraging of activities, I leave it be, or to even emphasize its essential properties. On the other hand, if it obstructs the flow of activities, it should be erased. Another essential reason is the view that we wish to see it from the inside.

Shen: A single viewpoint in this design does not exist as it is a multi-directional structure, and people will gradually discover new spaces while moving through them. The existing slope on the northern edge is a great activity space for children, so we were troubled by how the design could best respond to this slope. In the end we decided to create an even wider staircase, to connect the building with the columns, and to extend the existing slope for children so they could run freely through new and existing spaces.

Shen: The concrete walls on the southern edge were the earliest structures to appear. The initial outline was for the architecture to embrace the power of the land by penetrating the existing soil wall, and in addition creating an east-west connection. Coincidentally, the parking lot cannot be seen from the inside, leaving only the view of the mountains and the tips of the trees.

Shen: The scale of the existing corridor and the newly built eaves almost overlap on the plan drawing but are separated by different heights. From a structural viewpoint, if an earthquake occurs, the new building will not affect the existing buildings. However, the independence of the new building is more significant to me, as I wanted them to differ in terms of personality but still communicate with one another.

Shen: Enabling people in the second-floor corridor on the west to investigate the activity space and the playground on the upper levels creates a dramatic relationship between different levels, and also bestows a flexibility of usage around the activity space. This further creates a connection of the senses across the entire schoolyard. My intention was for people to move through a transitional space before entering the building. In addition, the design elements at each edge were an attempt to imitate existing structures, to extend space and devise an architectural language.

대만 4세대 건축가의 특질

쉔 팅 쳉은 대만 자이 시 출신으로, 타이베이에 기반을 둔 쉔 팅

쳉 아키텍츠를 설립했다. 건축, 환경, 자연의 관계를 재해석하는 것을 바탕으로 건축물 각각의 역할에 적합한 형태를 찾고, 시적이고 새로운 공간을 설계하고자 한다. 대표 프로젝트로는 라이트

하우스(2016), 플로팅 파빌리온(2016), 자이 기차역

광장 리노베이션(2017), 시지안대학교 건물B(2018) 등이

있다.

각국의 건축가들은 이전 세대와 다른 행보로 저마다의 차이를 만들어가고 있다. 그 가운데 대만은 근현대의 역사적, 사회적 환경이 역동적으로 변화해왔고, 이에 따라 건축계의 지형도도 바뀌어 왔다. 현시점 대만은4세대 건축가들의 활동이 본격적으로 태동되고 있다. 그중 쉔 팅 쳉의

언어와 작업을 가까이 들여다보고자 한다. 그가 생각하는 건축의 과정과 건축이 가 닿을 수 있는 영역에

대해 묻고자 한다.

박창현(박): 한국과 대만은 공통적으로 일제 식민지기를 겪었다. 제2차 세계대전을 기점으로 많은 정치적, 역사적 변화를 겪었는데 그 과정에서 대만 건축도 많은 변화가 있었을 것 같다. 대만 건축의 근현대 역사의 흐름을 간단하게 듣고 싶다.

쉔 팅 쳉(쉔): 대만의 현대건축은 일제 식민지기인 제2차 세계대전 이전에 시작되었다. 1930~1945년 즈음 일본은 기차역, 철도, 전매청, 설탕 정제소와 같은 기반시설을 대량으로 건설하면서 콘크리트, 강철을 이용한 건설 기술을 도입했다. 전후 대만은 정부의 영향으로 중국적 특징을 가진 건축을 장려하는 문화적 르네상스를 겪었지만 서양 모더니즘의 아이디어도 동시에 꽃피기 시작해 건축에서 두 개념이 역설적으로 충돌하면서 독립적으로 존재했다. 1970~1990년대는 급속한 도시화의 시대였다. 지역 산업과 부동산의 부상으로 도시가 고밀도화, 현대화됐다. 1990년대 말, 사회가 전반적으로 자유화되고 정치적 이념이 중국에서 멀어지면서 풀뿌리 운동이 서서히 추진력을 얻었다. 건축가들은 기능에 초점을 맞춰 대만에 적합한 건축물을 설계했고 이후 몇 년에 걸쳐 다양한 지역 건축이 촉발됐다. 2010년 이후 다양한 하위문화와 온라인 미디어가 등장했고, 이는 건축의 경계에 영향을 미쳤다. 미술, 설치, 전시 등이 건축의 디자인 요소로 거듭났고, 건축적 사고는 지역에 국한되지 않고 보다 기본적이고 단순하며 순수한 개념으로 변모하는 과정을 거치고 있다.

박: 한국과 매우 흡사한 역사를 가지고 있는 것 같다. 일본이 만들어 놓은 기반시설을 바탕으로 국가 주도의 건축 이미지를 전통과 연계하려 했던 시도가 한국에도 있었고, 그 중심에 있는 건축가가 시기별로 존재했다. 제2차 세계대전 이후 대만 건축을 이끌어간 건축가들은 누구인가?

쉔: 1세대 대만 건축가들은 1915~1935년에 중국에서 태어나 서구 모더니즘 건축 교육을 받았고 그들의 건축은 주로 자국의 근대화에 대한 논의로 이루어졌다. 이 시기에 두각을 나타낸 건축가로는 대만 모더니즘 건축의 선구자 중 한 명인 왕 다 홍(1917~2018), 대만 퉁하이대학교 캠퍼스와 루스 기념 채플을 설계한 건축가이자 예술가이자 교육자인 천 치 콴(1921~2007)이 있다. 2세대 건축가는 1935~1955년에 태어난 건축가들로, 경제가 발전하기 시작하고 부동산 개발이 부흥하는 등 빠르게 발전하는 대만을 목격하며 자란 세대다. 그들은 문화, 상업, 건설 기술, 모더니즘, 포스트모더니즘의 건축적 영향을 허물기 위해 노력했다. 이 시대의 대표적인 건축가는 대만의 랜드마크인 타이베이 101을 설계한 추 유안 리(1938~), 신추고속철도와 란양박물관을 설계한 크리스 야오(1951~)가 있다. 이어서 1955~1975년에 태어난 3세대가 등장하는데, 당시는 사회정치적 분위기가 자유화되고 사람들이 민주주의를 향하던 시기였다. 시대상에 맞게 건축도 사람, 땅, 환경에서 영감을 얻은 지역 건축이 시작됐고 보다 열려 있고 대중과 소통하는 건축이 등장했으며 쉥-유안 황과 제이 추가 그러한 건축을 했다. 마지막으로 4세대는 1975~1985년에 태어났는데, 개인적으로 이 세대의 건축가들은 이전 세대가 환경을 대하는 태도에 영향을 받은 것 같다. 그러나 지역에 영향을 받는 경향은 줄어들어 세계를 그 자체로 받아들이는 듯하다. 표준화, 세계화, 자본주의와 같은 주제에 맞서고 있는데 아마도 현대미술과 건축 이념의 부활, 소규모 건축이 그들에게 영향을 미쳤을 것이다. 이들은 내재적인 표현, 사람의 감각과 건축과의 상호작용, 작품이 아닌 건축을 하려는 시도를 하고 있다.

박: 건축을 문화와 건물의 결합이라고 본다면, 대만 건축에서는 문화적 가치를 부여하는 방식이 어떻게 발현되고 있는가?

쉔: 건축을 문화에서 독립시킬 순 없지만, 문화적 가치만을 표현하려는 건축은 지나치게 경직된다. 대만 문화의 가치를 정의하기란 참 어렵다. 대만 사람들만의 독특한 생활방식이 있고, 지금도 모든 분야가 저마다의 가능성과 가치를 탐구하고 있으며, 대만 문화의 재발견과 재건의 시기를 맞고 있는 현재로서는 건축가가 확신을 가질 수 있는 단일한 문화적 영감은 존재하지 않는다. 우리는 더 이상 문화를 표현하는 것을 열망하지 않는다. 오히려 개인적 경험에 집중하면서 저마다 새로운 것을 지속적으로 시도하고 있다.

박: 당신의 프로젝트를 살펴보면, 기존 건축물에 새로운 공간을 만들어 활력을 불어넣는 경우가 많다. 도심에서 사람들을 모으고, 에너지를 이끌어낼 때 어떤 태도를 취하는가?

쉔: 건축은 때때로 뜻하지 않게 사람들의 삶의 질을 방해하기도 한다. 그렇기 때문에 나는 건축을 일종의 촉매로 생각하려고 한다. 임시적이든 영구적이든, 촉매로서의 건축에 있어서 핵심 아이디어는 동일하다. 가령 건물의 배치를 통해 더 활기찬 일상을 이끌어내거나 때로는 사람들에게 변화를 경험하게 하는 등의 영향을 고려한다. 하지만 이러한 종류의 건축이 삶의 짧은 순간만을 사로잡으려는, 장식적으로 접근하는 태도에는 반대한다. 기존 환경과 공존하고, 기대고, 충돌하며 새롭고 근본적인 삶의 흐름을 만드는 건축을 하고 싶다.

박: 건축이 사회에 영향을 미치는 범위가 점점 더 커지고 있고, 어떤 건축물은 존치되는 시간과 무관하게 그 영향력이 강력한 경우가 있다. 그런 의미에서 ‘플로팅 파빌리온’(2016)은 TFAM 광장에 3개월이라는 짧은 기간 동안만 지속됐음에도 광장에 대한 기존의 기억을 한 번에 전복시킬 만큼 영향력이 컸을 것 같다. 파빌리온을 통해 어떤 변화들을 불러일으키고 싶었는가?

쉔: 광장은 바람과 햇빛이 강해서 사람들이 이곳의 공간을 온전히 느끼기에는 어려움이 있었다. 이 극한의 자연을 포착하는 반투명한 연으로 플로팅 파빌리온을 설계하여 사람들이 충분히 이곳을 경험하고 기억하도록 했다. 사람들은 파빌리온의 독특한 느낌에 매료되어 공간에 애착을 가지게 되는데, 이는 파빌리온의 장소감에 큰 영향을 미친다. 더불어 임시 건축물로서 약하고 불안정한 성향이 있는데, 이는 건물과 자연의 연결을 더욱 긴밀하게 해 바람, 빛 등의 자연 요소가 파빌리온 안에 존재하게 한다. 불안정한 건축적 요소가 자연적 요소와 만나면 인간에게 적합한 스케일로 부드러운 장을 형성한다.

박: 파빌리온이 위치했던 TFAM 광장에는 타이베이 파인 아트 뮤지엄이 있다. 이 건물과의 연계에 있어서는 어떤 고민이 있었나?

쉔: 타이베이 파인 아트 뮤지엄의 건축적 요소에서 연관성을 만들고자 했다. 예를 들어 네모난 박스 연으로 만들어진 파빌리온의 그리드는 뮤지엄 로비의 그리드 보에 대한 응답이었다. 하지만 이 두 구조는 부모와 자식처럼 크고 작은 스케일로 서로의 거리를 유지했다. 파빌리온이 박람회의 회전목마처럼 독립적으로 떠 있기를 원했다.

박: 바람이 있어야 기능을 하는 연을 활용한 점, 동시에 연이 그늘의 역할을 하여 공공을 위한 장소가 되는 점이 흥미롭다.

쉔: 연은 바람으로 인해 그 형태가 결정된다. 유연성, 불안정성, 반투명성, 가벼움 등의 성질을 갖춘 연은 현장 조건과 강하게 연계된다. 나는 그림자와 함께 구조적 가벼움을 표현했다. 또한 연을 사용하기로 결정한 것은 개별적으로 분리된 스케일을 의식했기 때문이다. 3개월간의 설치가 끝난 후 파빌리온에 사용된 300개의 연은 어린이를 위한 장난감으로 개작됐다.

박: 파빌리온은 기능과 용도가 모호하고 다양한 건축 유형이다. 그만큼 도시에서 하는 역할의 폭도 넓을 텐데, 플로팅 파빌리온을 계획할 당시 이곳이 어떻게 사용되기를 바랐나? 그리고 실제로는 어떻게 사용됐나?

쉔: 파빌리온의 목적을 제한하지 않았다. 다만 규모를 가볍고 변환 가능하도록 계획했다. 이 프로젝트에 접근하는 사람들이 자유롭고 편안함을 느꼈으면 했다. 실제로 현장을 방문했을 때 부모와 자녀가 파빌리온에 앉아 바람을 느끼거나 담소를 나누거나 책을 읽는 모습을 봤다.

박: 캐노피 아래로

내려오는 섬을 닮은 곡선의 볼륨은 사람들의 행동을 유도하는 성격도 띠는 듯 보인다. 그리고 곡면으로

인해 내부 소리의 환경에도 변화가 있을 것 같은데, 설계 의도가 궁금하다.

쉔: 나는 열린 공간을 계획할 때 항상 ‘활기찬 평화’를 가져오기 위해 교묘하게 수렴되는 무언가를 원한다. 곡선형 섬의 외부는 사람이 기댈 수 있는 공간을 제공하고 내부는 바람과 소리와 같은 자연 요소를 모은 그릇과 같다.

박: 최근에 진행한 ‘사네초등학교: 반외부 공간’(2021)도 궁금하다. 기존 건물에 학교에서 필요로 하는 비를 피할 수 있는 반외부 건물을 더하는 프로젝트였기 때문에 두 건물의 양식적, 형식적, 구조적, 재료적 관계 설정이 중요했을 것 같다. 기존 건물과 연결하고 싶었던 것은 무엇이고, 이를 어떻게 설계로 녹여냈는지 이야기를 듣고 싶다.

쉔: 현장에 있는 놀이터가 두 건물의 연결을 이끌어내는 원천이다. 포인시아나 나무와 놀이기구가 있어 아이들을 자연스럽게 놀이터로 끌어들이고, 이러한 자연스러운 놀이가 수업 시간뿐 아니라 쉬는 시간에도 이루어졌으면 했다. 내가 그렸던 건축의 이미지는 자유로운 형태를 가진 인공의 경계다. 기존에 있던 외부 요소들과 상호작용하면서 건물의 매스를 안정적으로 둘러싸는 그런 경계를 상상했다.

박: 빈 장소에 새로운 건물이 들어설 때 주변과의 관계, 사용자들의 인식이 어떻게 변화하는지가 중요하다고 생각하는데, 이 프로젝트는 몇 개의 간단한 제안으로 기존에 있던 주변의 질서와 관계를 재정립한 느낌이 든다.

쉔: 건축은 내부 공간을 생성할 가능성이 크지만 동시에 외부 관계를 규제할 수 있는 무한한 잠재력을 지니고 있다. 내 생각에는 이 두 요소가 모순되지는 않지만 설계 과정에서 종종 모순에 직면하게 된다. 개인적으로 새로 들어선 이 활동 공간이 기존의 주변 질서를 재정립할 수 있는 특별한 조화로움을 갖기를 바란다. 새 건물이 기존 건물을 배제하거나 차단하지 않도록 경계하는 것이 중요하다. 따라서 배치를 계획하면서 디자인과 기존 건물 사이에 약간의 공간을 남겨놓았다. 그 거리는 미묘한 장력과 공간 사이의 전환을 만들기 위해 적절하게 남겨두어야 한다.

박: 기존에 있던 요소들은 크게 남길 것, 지울 것, 수정할 것으로 나뉜다. 각각을 결정하는 기준은 무엇이었나?

쉔: 기존 건물의 요소가 사람들의 ‘활동’을 장려한다면 그대로 유지한다. 심지어 강조하기도 한다. 반대로 새로운 결과물이 기존 ‘활동’의 흐름을 방해한다면, 그 요소는 없앤다. 또 다른 본질적 기준은 우리가 내부에서 보고자 하는 경관과 관련된다.

박: 기존 건물과 새로운 건물의 높이를 조율할 때에는 무엇을 염두에 두었는가? 기존 건물의 서측 경사로 옆에 나란히 계단을 다시 설치해 병치한 것이 흥미롭다. 기능상 새로운 연결이 필요한 상황은 아니었음에도 불구하고 이 계단을 설치한 특별한 이유가 있었는가?

쉔: 이 디자인은 하나의 관점, 하나의 방향을 가리키지 않는다. 다양한 방향성을 가지는 구조로, 사람들이 그 사이를 돌아다니면서 점진적으로 새로운 공간을 발견하도록 설계했다. 기존 북측 경사면은 아이들이 놀기 좋은 공간이라 이 경사면에 어떻게 대응해야 할지 고민을 많이 했다. 결국 더 넓은 계단을 만들어 건물의 형태와 기둥을 연결하고 기존 경사를 확장하여 아이들이 새로운 공간과 기존 공간을 자유롭게 뛰어다니고 활동할 수 있도록 계획했다.

박: 동측 계단의 폭을 줄이고 벽을 설치했는데 주차장이나 조경 영역과의 분리에 대한 생각을 듣고 싶다.

쉔: 남쪽 가장자리의 콘크리트 벽은 가장 먼저 나타나는 구조물이다. 초기 목적은 건축이 기존의 흙벽을 관통하여 대지의 힘을 받아들여 동서 방향을 연결하는 것이었다. 하지만 공교롭게도 내부에서는 주차장이 보이지 않아 결과적으로 산과 나무의 끝자락만 보이게 되었다.

박: 기존 건물의 캔틸레버 보와 새 건물의 구조가 위치상 연결되지 않고 간격이 있는 점, 새 건물의 하부 구조는 콘크리트, 상부 구조는 철골로 계획한 점 등 미묘한 지점들이 발견된다. 구조를 계획하면서, 특히 지붕을 계획하면서 중요하게 생각했던 점이 무엇인지 궁금하다.

쉔: 기존 회랑과 새로 지은 처마는 평면도에서 거의 겹치지만 단면적으로는 분리된다. 구조적 관점에서 지진이 발생해도 새 건물은 기존 건물에 영향을 미치지 않는다. 새 건물의 독립성은, 성격을 구분하며 여전히 서로의 소통을 유지하기에, 나에게는 중요한 의미가 있었다. 건물 전체를 강철로 지었다면 규모가 너무 크고 느닷없어 보였을 것이다. 그래서 재료의 전환이 대지와 혼합되도록, 건물과 환경을 연결하는 동시에 수평적 순환을 만들도록 했다. 또한 지붕은 기울어져 있어 공간의 방향을 시각적으로 알려주고 사람들이 나무와 공간의 관계를 인지하도록 유도한다.

박: 북측에서 봤을 때, 기존 건물과 새 건물의 높이 차가 발생하는 점이 재미있다. 1층에서는 낮게 공간을 납작하게 눌러 계획했고, 2층 발코니에서는 새로운 건물의 내부를 볼 수 있게, 그리고 지붕의 레벨도 미묘한 변화가 있다. 기존 건물과 운동장의 레벨의 연결에서 중요하게 고려한 점은 무엇이었는가?

쉔: 서쪽의 2층 복도에서 사람들이 활동 공간과 위층의 놀이터를 볼 수 있도록 하면 층 사이의 극적인 관계를 만들 수 있으며 공간을 유연하게 사용할 수 있다. 그러므로 전체 학교 운동장에서의 감각적 연결을 강조한다. 운동장에서 교실로 진입하는 과정의 연결성에서는 사람들이 건물에 들어가기 전 전환을 느끼는 것도 중요한 내용이었다. 또한 각 모서리의 디자인 요소는 기존 구조를 모방하여 공간과 건축의 언어를 연결하고 확장하려는 시도였다.

Shen Ting Tseng Architects_ Shen Ting Tseng

ON THE BORDER BETWEEN ART AND CAPITAL: SMALL PROJECTS

Shen Ting Tseng, born in Chiayi, Taiwan, is

the founder of Shen Ting Tseng Architects. The architecture firm is based in

Taipei, Taiwan. With the standpoint of reinterpreting the relationship between

architecture, the environment, and nature, the team pursues appropriate forms

for every role in each architecture and creates new spaces and living settings

that are authentically poetic. Representative projects include Light House

(2016), Floating Pavilion (2016), Renovation of Chiayi Railway Station Square (2017),

and Shih Chien University Building B (2018).

Architects in each country have taken their

own steps and launched their own challenges to the generations that preceded

them. Taiwan has witnessed a change in architectural topography in respect to

the historical environment. To reflect upon the present situation in Taiwan, I

have chosen to interview Shen Ting Tseng, one of the young architects in the

fourth generation of Taiwanese architecture visibly expressing his own

language. I was curious to hear his thoughts on architectural processes and the

expansion of architectural boundaries.

Park Changhyun (Park): Taiwan and South Korea have undergone a great deal of political and historical change since World War II. Architecture has also evolved in remarkable ways during this period. I would like to hear about Taiwan's celebrations after World War II, and a brief introduction the current trend of Taiwanese architecture.

Shen Ting Tseng (Shen): Taiwanese modern architecture started before World War II, during the Japanese colonial rule. Between 1930 -1945, the Japanese introduced concrete and steel construction techniques while building vast infrastructural networks and facilities such as train stations, railways, the Monopoly Bureau, and sugar refineries. While post-war Taiwan experienced a renaissance in Chinese culture, in which the government encouraged the production of architecture with Chinese features, the idea of Western modernism had also begun to blossom simultaneously, resulting in clashes or independent occurrences of both concepts in architecture. 1970 -1990 was an era of rapid urbanization-with the rise of local businesses and real estate, cities developed a higher density and further modernization. At the end of the 1990s, as society had become more liberal as a whole and political ideologies had strayed from China, grassroots movements slowly gained momentum. Consequently, architects turned their focus to real living spaces, attempting to create designs suited to Taiwan, sparking a diverse regional architecture movement that would stretch out over the years. After 2010, Taiwanese culture has been probed wide and deep, creating a colorful array of subcultural and online media, which in turn has shifted the boundaries of architecture. Art, temporary installations, exhibitions, and more others have become elements in architectural designs, whereas architectural thinking has strayed from regional limitations and morphed into a more basic, simpler, purer version of what it once was.

Park: This is connected to history of

Korea, and the identity and interests of each generation follow the same

historical stream. What do Taiwanese young architects choose to focus on and

how is this focus changing?

Shen: The first generation of Taiwanese architects originated in 1915 - 1935, predominately born in China and educated in the Western world, so their architecture was a discussion of the modernization of Chinese architecture. The most significant architects during this era were Da-hong Wang and Chi-kwan Chen. The second generation of architects were born in 1935 -1955. They faced a rapidly developing Taiwan, when the economy was just taking off and cities grew with the development of real estate. As a result, they struggled to break through the boundaries of culture, business, construction techniques, modernism, and postmodernism. The representative architects are Chu-yuan Lee and Kris Yao. The third generation was born in 1955 -1975, when the political atmosphere became more liberal, and people worked towards a democratic society. At this moment, regional architecture movements drew inspiration from people, the land, and the environment, attempting to open architecture up to and encourage the public. The representative architects are Sheng-yuan Huang and Jay Chiu. The fourth generation were born in 1975 - 1985. In my opinion, this generation of architects were influenced by the former generation in terms of environmental thinking. However, regional influences were lessened as they accepted the world as a whole and fought against themes such as standardization, globalization, and capitalism. Perhaps it was modern art and the revival of architecture ideology, along with the privileging of architecture on a smaller scale that had the greatest impact on these architects, so they redirected their focus on internal expression and on sensory engagements with architecture, forming the basis of their attempts to return their labors to architecture.

Park: Architecture cannot exist alone. Considering architecture as emerging from the combination of culture and structural programs, what attempts that concern cultural values are presently being undertaken in Taiwan?

Shen: Although architecture cannot be separated from culture, it becomes overly rigid when it is too eager to express cultural values. It is difficult for me to define the value of Taiwanese culture as people are still exploring the possibilities and values across every field, and even though people in Taiwan do have a unique lifestyle, Taiwanese culture is facing a time of rediscovery and reconstruction. For architects, a single reliable cultural source does not exist. We are retracing our steps to focus on individual experiences, no longer anxious to express our culture, but to continuously reflect and make new attempts.

Park: There are many of your projects that intend to create new spaces whether in existing buildings or in the city, to introduce greater dynamism for residents in the city. What do you think of buildings that bring people together and create new energy in the city center?

Shen: Architecture sometimes accidentally obstructs living possibilities, so I like to think of architecture as a catalyst, deriving a livelier lifestyle from architectural assemblages, sometimes providing a chance for people to experience the exhilaration of change. Whether it is temporal or permanent event, the core idea of architecture as a catalyst is the same. However, this sort of architecture is often very noticeably decorated, like a cardiotonic that produces only an instant of life. I am against this approach; I want to create architecture that will coexist, depend upon, or even collide with its existing environment, creating a new but profound flow in life.

Park: The extent of architecture’s impact on society is expanding. Regardless of the time when the results made in the place are present, I think the influence becomes more intense. In this sense, Floating Pavilion (2016) has the power to be approached by anyone and to subvert or change one's existing impressions of the previous square. Keeping in mind the Floating Pavilion installed in TFAM Square for three months, can you detail any different situational changes?

Shen: Due to the strong winds and scorching sunlight acting on the pavilion, people could not experience the space in an ordinary way. During the three-month exhibition of the Floating Pavilion, we tried to capture this extreme bout of weather through half-transparent kites, turning this experience into one that could be felt and remembered. Once enraptured by a unique feeling in a space, people get attached, and this plays a major part in the pavilion's sense of place. Temporal architecture tends to be more vulnerable and unstable, which further enables correspondence between the project and nature. On the outside, this pavilion may appear lackluster, but it is home to rich natural elements of wind and light. When unstable architectural elements are met with natural elements, together they form a soft field on a scale suitable for people.

Park: At the time of the Floating Pavilion installation, did you have any thoughts about the connection of TFAM Square to the Taipei Fine Art Museum located next door?

Shen: I attempted to create continuity in the architectural elements of Team, for example the grid the box kites created was a response to the grid beams in the lobby. Though familiar, the two kept their distance, one large and one small, like a parent and a child. Perhaps I wanted the pavilion to float independently, like a carousel in a fair.

Park: It is interesting to use kites that

function only when there is wind, and I think it is a smart idea to create a

public place that acts as a shadow at the same time.

Shen: The box kites take flight due to the wind that blows through its dimensions; equipped with flexibility, instability, dimension, and a translucent, light appearance, the kite has a strong connection with the site conditions. It brings a lightness to the structure and creates playful shadows. In addition, the decision to use kites implies thinking on an individual scale, and after the exhibition, the three hundred kites that were used will become toys for children.

Park: A pavilion is a functionally ambiguous, nonpermanent building of various purposes, and I think the roles it can adopt within the city are so diverse. What activities can you discover in that space while also providing people with a shared space?

Shen: On site, we observed that there were parents and children, people that just sat there experiencing the wind, chatting, or reading. By not limiting the project to a clear purpose, and insisting upon a strict but persuasive scale, people that approach this project feel free and relaxed.

Park: The shape of the curved island under the canopy seems to welcome not only curved sides but the various shapes created by visitors. And there's also a change to sound quality inside, what was the intention or process behind designing such content?

Shen: When planning open spaces, I always hope something will converge silently, calling forth a 'lively peace'. The outside of the curved island provides a space for people to lean on, while the interior is like a bowl that gathers natural elements like the wind and sound.

Park: I'm also curious about your latest project, Sahne Elementary: Semi-outdoor Activity Space (2021). Semi-outdoor building in which people can shelter from the rain was added to the existing school. I felt it was important to establish a stylistic, formal, structural, and material relationship between the existing and new buildings.

Shen: The playground on the site is a source of creating connections. There are poinciana trees and recreational equipment that naturally draws children into the playground, so I wanted to extend this natural playfulness to the new activity space, as it should not only be used during classes, but also during recess. To create the ideal connection with its surroundings, I had to imagine architecture as a freeform, plastic boundary, interacting with the existing exterior elements, the enclosing it within a stable architecture mass.

Park: I think it is important to alter the surrounding relationships and the perception of users when a new building is built in an empty place. I feel like that this project reestablishes the existing surrounding order and spatial relationships with some simple suggestions.

Shen: Architecture indeed possesses the ability to create inner space, but at the same time it harbors the infinite potential to regulate exterior relationships. In m>opinion, these two are not contradictory elements, and yet during the designing process we are often faced with contradictions. I do hope this activity space adopts a special orientation, which can also reestablish the existing surrounding order.

Park: As the layout is determined, tasks are divided into what is left on the ground, what needs to be erased, and what needs to be modified. That approach connects necessary development smoothly with existing buildings or contexts. What criteria did you use to decide what to leave, erase, or modify in the new space?

Shen: If the existing elements are encouraging of activities, I leave it be, or to even emphasize its essential properties. On the other hand, if it obstructs the flow of activities, it should be erased. Another essential reason is the view that we wish to see it from the inside.

Park: Is there a view that you considered important at the level of the existing building and the level of the new building?

Shen: A single viewpoint in this design does not exist as it is a multi-directional structure, and people will gradually discover new spaces while moving through them. The existing slope on the northern edge is a great activity space for children, so we were troubled by how the design could best respond to this slope. In the end we decided to create an even wider staircase, to connect the building with the columns, and to extend the existing slope for children so they could run freely through new and existing spaces.

Park: You have reduced the width of the eastern stairway and installed a wall. I would like to hear your thoughts on the separation between the parking lot and landscaped area.

Shen: The concrete walls on the southern edge were the earliest structures to appear. The initial outline was for the architecture to embrace the power of the land by penetrating the existing soil wall, and in addition creating an east-west connection. Coincidentally, the parking lot cannot be seen from the inside, leaving only the view of the mountains and the tips of the trees.

Park: The location of cantilever beams in the existing building and the structure of the newly built space has not been connected. Is the gap between structures considered separately?

Shen: The scale of the existing corridor and the newly built eaves almost overlap on the plan drawing but are separated by different heights. From a structural viewpoint, if an earthquake occurs, the new building will not affect the existing buildings. However, the independence of the new building is more significant to me, as I wanted them to differ in terms of personality but still communicate with one another.

Park: The difference in level across the cross-section of the existing building in the North is interesting. On the first floor, the space was planned to be flat, and on the balcony on the second floor, the interior of the new building could be seen, while the roof level was als0planned with subtle changes. What was important about the connection between the existing buildings and playground levels?

Shen: Enabling people in the second-floor corridor on the west to investigate the activity space and the playground on the upper levels creates a dramatic relationship between different levels, and also bestows a flexibility of usage around the activity space. This further creates a connection of the senses across the entire schoolyard. My intention was for people to move through a transitional space before entering the building. In addition, the design elements at each edge were an attempt to imitate existing structures, to extend space and devise an architectural language.