방콕 프로젝트 스튜디오_ 분섬 프렘타다

자연과 인간을 연결하는 건축

분섬 프렘타다는 태국 방콕에서 태어나고 성장했다. 태국의 출라롱콘

대학교에서 인테리어 디자인을 전공(1988)하고 건축학 석사학위

(2002)를 받은 뒤 2003년에 방콕 프로젝트 스튜디오를 설립했다. 그는 건축이 자연에 대한 인간의 인식을 높이는 물리적 환경을 창조하는 일이라는 신념을 가지고 빛, 그림자, 바람, 소리, 냄새의 감각적 경험이 살아있는 ‘건축 시학’을 추구한다. 소외된 사람들의 삶을 개선하는 여러 프로젝트를 선보인

그의 작업은 이론과 실천을 아우르며 사회, 경제, 문화적

의제들을 다룬다.

박창현(박): 태국 북동부

수린 주(州) 반타클랑에 위치한 엘리핀트 월드는 코끼리와

코끼리를 사육하는 쿠이(Kui)족의 삶의 터전을 10년에

걸쳐 조성한 프로젝트다. 코끼리와 사람이 공존하는 건축이라는 점에서 호기심을 자극한다. 프로젝트가 시작된 배경과 진행 과정이 궁금하다.

분섬 프렘타다(프렘타다): 수린 지방행정부에서 담당 건축가로 초청해 이 프로젝트에 참여하게 되었다. 태국에서 코끼리는 일반적인 동물과 위상이 다르다. 성스러운 대상으로 왕실 의식에 참여하기도 하며 장거리 이동, 건설 현장, 전쟁 둥에 다양한 형태로 동원되기도 했다. 태국사람들은 코끼리를 반려동물이나 노동력이 아닌 사람과 동등한 ‘가족’으로 여긴다. 쿠이 마을은 태국 내에서도 손꼽히는 코끼리 주요 서식지이다. 수세기 동안 이 지역 사람들은 태어나서 죽을 때까지 일생을 코끼리와 함께 살아왔다. 하지만 산업화가 가속되고 코끼리의 자리를 기계가 대체하면서 코끼리와 코끼리 사육사들은 돈을 구걸하거나 숲에서 일거리를 얻기 위해 방콕, 치앙마이, 푸켓 등타지로 떠나야 했다. 정부예산을 받아 이 지역을 되살리고 재건하기 위해 코끼리와 코끼리 사육사를 이 마을에 정착시켜 동물학대 문제를 논의하고, 숲을 복원해 코끼리들의 먹이와 수원을 되살리는 것이 프로젝트의 주된 목표였다.

박: 프로젝트가 쿠이 마을, 코끼리

병원, 사람과 코끼리 모두를 위한 사찰과 묘지까지 포괄하여, ‘사람과

코끼리가 함께 커뮤니티를 형성한다’는 점이 매우 흥미롭다.

프렘타다: 쿠이 마을은 400년 이상 된 코끼리 사육사들의 마을이다. 마을에는 사람과 코끼리 모두를 위한 종교의식을 행하는 파아지앙 사원이 있다. 코끼리묘지는 이 사원의 일부로 코끼리들이 죽으면 이곳에 묻힌다. 코끼리 병원에서는 코끼리만 전문적으로 진료하는 젊은 수의사들이 있다. 일련의 시설들은 엘리펀트 월드를 시작하기 전부터 원래 있던 것들이다. 이 프로젝트의 목표는 첫째로 지역 문화 보존, 둘째로 코끼리들의 먹이와 약초재배를 위한 숲의 복원, 마지막으로 코끼리와 쿠이족의 생활양식을 존중하는 관광사업을 꾸준히 유치해 경제적으로 자급자족할 수 있는 커뮤니티를 형성하는 것이다. 머지않아 여러 도시에서 떠돌고 있는 태국전역의 코끼리들이 이곳으로 모이게 될 것이다.

프렘타다: 나는 지금껏 인간 중심의 건축을 해왔기 때문에 이번에는 코끼리에 초점을 맞추려고 했다. 동물원은 인간과 동물을 분리하고 동물들의 삶을 진열하기 위한 공간이다. 하지만 나는 ‘코끼리를 위한 건축’을 통해 인간이 자연 속에서 큰 동물과 공존하는 법을 배우고, 인간을 비롯한 다른 생명체들의 가치를 인지하고 공감하는 법을 알리고자 했다. 쿠이족은 코끼리를 위해 살고, 코끼리들은 쿠이족을 위해 산다. 따라서 엘리펀트 월드는 코끼리와 유대를 만들어가고 있는 마을 사람들의 마음가짐인 ‘사랑'을 반영한다. 정부는 쿠이족이 돌보고 있는 코끼리에게 봉급을 주는데, 코끼리가 죽으면 그 주인은 봉급을 받지 못한다. 그래서 쿠이족사람들은 코끼리에게 각각 이름을 붙여주고 제자식처럼 아끼고 돌본다. 심지어 먹을 것이 없을 때에도 자신들은 굶을지 언정 코끼리의 먹이를 먼저 챙길 정도다. 이곳의 건축은 인간과 코끼리 사이의 배려를 강조하며 이들의 관계를 강화하는 연결고리 역할을 한다.

프렘타다: 과거에 투자자들은 이곳의 국유림에 환금작물을 재배하기 위해 숲을 훼손하고 땅을 잠식했다. 그 결과 수린 지역 일대는 물부족으로 태국에서도 가장 극심한 가뭄을 겪었고 1년내내 무더위에 시달려야 했다. 숲을 복원하는 데 긴 시간이 걸리기 때문에 건물을 지으면서 기존 자원을 최대한 활용하는 방식을 택했다. 빗물 집수용 연못을 파고, 여기에서 나온 흙을 이용해 벽돌을 만들어 원형극장을 비롯한주요 건물들의 자재로 사용했다. 연못은 숲과 코끼리, 사람들에게 영양을 공급하는 수원이 되었다. 벽돌전망대는 그 위에 올라 지역 식생의 씨앗을 바람을 타고 주변으로 퍼뜨리는 역할을 함으로써 숲의 복원에도 힘을 보탤 것이다.

프렘타다: 내가 프로젝트에 참여하기 전에 수린 지방행정부에서 이미 마스터플랜을 세우고 몇몇 건물의 설계와 시공을 완료한 상태였다. 나는 마을에서 출발해 세 건물로 이어지는 코끼리 ‘산책로’를 배치의 핵심 개념으로 생각했다. 대지 레벨이 가장 높은 곳에 벽돌전망대를, 가장 낮은 곳에 코끼리박물관을 두고 이 둘을 문화마당으로 구분했다. 세 건물 모두 주변의 숲과 연못으로 이어지며, 점차 낮아지는 건물의 높이와 개방성, 외형은 주변과 어우러져 풍경의 일부가 된다.

프렘타다: 문화마당은 마을사람들이 오랫동안 행해온 마을 고유의 신앙과 문화와 관련된 행사를 위한 공간이다. 쿠이족의 전통 의례와 행사들은 원래 친척과 이웃, 코끼리들이 다같이 모여 집에서 치러졌다. 이런 행사들이 열리는 문화마당은 관람객들이 여기에 동참하고 쿠이족의 일상을 목격할 수 있는 거대한코끼리 집의 의미를 담고 있다.

프렘타다: 숲 한 가운데 넓은 공터를 가진 사람들의 집에서 200마리가넘는 코끼리들이 함께 살고 있다는 사실이 너무 놀라웠다. 이곳의 장소, 사람, 코끼리의 스케일을 통합하여 건물이 익숙한 풍경의 일부가 되게 함으로써 둘사이의 균형을 찾고 ‘자기 중심적인'사람의 비중을 낮추고자 했다. 이를 위해 내가 생각 한 방식은 구축 행위를 최소화하고 열린 공간을 가급적 그대로 남기는 것이다. 문화마당은 사람들이 코끼리의 일상에 적응할 수 있도록 계획됐다. 흙으로 덮인 곳은 코끼리를 위한 영역이고 현무암으로 만든 원형극장은 사람을 위한 영역이다. 둘 다 지역에서 쉽게 구할 수 있는 재료다. 코끼리는 본능적으로 바위에 오를 수 없다는 것을 알고 있기 때문에 재료로 경계를 구분하고 환경과도 조화를 이루도록 했다. 벽이 없이 지붕만 있는 열린 공간, 흙 더미와 같이 친숙한 형태와 재료로 ‘차갑지 않은 공간’을 조성해 코끼리 에게 안락한 환경을 제공하는 것이 우선 과제라고 생각했다.

박: 문화마당의 바깥쪽은 평평하지 않고 굴곡진 흙 더미로 이루어져

코끼리들이 뒹굴 수 있다. 강이 4km 이상 떨어져 있기

때문에 코끼리들이 물장난을 할 영역이 필요했을텐데, 흙을 파서 언덕을 만들고 빗물을 모아 연못을 만든다는

아이디어는 어떻게 제안하게 되었나?

프렘타다: 문화마당은 코끼리가 먹고 마신 뒤 심신의 건강을 유지하기 위해 산책하고 운동하는 공간이자, 오래 집에 머무르며 쌓인 스트레스를 해소하는 공간이다. 나는 원형극장과 수공간 두 가지가 모두 필요하다고 생각했다. 국민의 세금으로 진행되는 프로젝트이기 때문에 최대한 기존 자원을 활용해 이 둘을 동시에 해결하는 것이 관건이었다. 총 8,600m³의 흙을 파내고 그 자리에 연못을 조성하면, 207마리의 코끼리들이 한 달 동안 사용할 수 있는 충분한 물을 확보하게 된다. 실상 나는 건물의 절반만 설계했을 뿐이다. 나머지 반은 자연, 코끼리, 쿠이 마을사람들의 작업이라고 할 수 있다.

프렘타다: 박물관에서 관람객들이 예상하지 못한 공간을 맞닥뜨리게 하고 싶었다. 아무것도 모르는 상태에서 쿠이족의 집 안으로 들어가 코끼리를 발견하거나, 숲 속을 걷다 우연히 코끼리를 마주치는 것처럼 말이다. 또한 나는 이곳을 쿠이족과 코끼리들 스스로 자신들의 역사를 이야기할 수 있는 구전(口傳) 형태의 박물관이 되도록 설계하고자 했다. 쿠이족은 지금까지 자신들의 삶에 대해 이야기할 기회가 없었다. 실향민이 된 처지, 생존을 위한 고군분투, 외지인들의 비난, 귀향, 삶의 방식에 대한 자부심과 힘에 대한 외침 등 행복과 고통, 고난이 깃든 400년 역사에 대해 스스로 말하기를 바랐다. 박물관안의 ‘소리’는 높낮이가 다른 벽을 타고 울림이 증폭된다. 여기서 시적인 요소는 인간의 기능적 언어가 아닌, 감각의 언어인 코끼리들의 소리이다. 코끼리도 우리처럼 감정을 가지고 있고, 부모와 친척도 있다. 코끼리 소리와 쿠이족의 음성은 다른 쪽에서 들려오는 ‘진실'의 소리로 듣는 이들의 마음속에 깊은 여운을 남길 것이다.

프렘타다: 박물관 설계는 내부와 외부가 공존하는 공간을 창조하는 일이었다. 중앙통로는 박물관내부의 실로 연결되며 건물 바깥으로 연결된 네 개의 출입구로 이어진다. 이 출입구들은 각각마을, 연못, 숲과 건물을 둘러싼 다른 통로로 이어진다. 관람객이 머무는 내부전시실은 박물관 실내 전시 영역의 두 배에 이르는 안뜰로 둘러싸여 있다. 안뜰은 이 지역의 햇빛, 비, 그림자, 바람, 소리가 자아내는 독특한 분위기를 그대로 담고 있으며, 이 모든 공간을 벽돌벽이 층층이 감싸고 있다. 물론 건물을 에워싸고 풍경과 연결시켜 통일성을 만들어내는 단단한 붉은 벽돌 벽 때문에 다른 쪽의 시야가 줄어들 수도 있지만, 나의 디자인을 통해 쿠이족과 코끼리의 이야기에 대해 인간의 모든 감각을 깨우고자 노력했다. 박물관 안을 거니는 코끼리들은 외부에 있는 듯한 공간감을 선사할 것이다.

프렘타다: 나는 사람들이 이 작은 구조물 안에서 가능한 많은 시간을 보내고, 시간대나 높이에 따라 다른 분위기를 경험하길 바랐다. 사람들은 계단을 따라 위로 올라갈수록 전망대가 층별로 모두 다른 방향을 향하고 있음을 자각하면서 다른 전망대처럼 꼭대기로 달려갈 필요가 없음을 느낄 것이다. 시간을 두고 천천히 작고 섬세한 것들을 발견하며 자신을 성찰하는 시간을 보내게 될 것이다.

프렘타다: 전망대는 잘 보존된 숲과 훼손된 숲의 경계에 있다. 높이 솟은 전망대는 숲을 복원하는 데에도 일조한다. 전망대 꼭대기 부분에는 시속 29~38km의 바람이 부는데, 전망대 반경 20m안에 여러 식물의 씨앗을 운반해 흩뿌릴 것이다. 그런 의미에서 전망대는 한때 파괴되었던 지역에서 다른 나무들의 생명을 낳는 첫 번째 나무’라고도 할 수 있다. 원래 전망대는 코끼리들의 발정기 때 사람들이 몸을 피할 용도로 디자인된 구조물이었다. 엘리펀트 월드 안에서 유일하게 코끼리가 들어갈 수 없는 건물로, 그 자체로 실내 공간, 통풍 및 조경 기능을 갖춘 공학적 구조물로 설계됐다.

프렘타다: 쿠이족은 가난하지만 돈으로 그들을 유혹할 수는 없다. 부모와 조부모 세대가 그러했듯 그들은 부를 위해 코끼리를 팔지 않을 것이다. 자신들의 이름을 내세워 기부하려는 기업이나 단체와 손잡고 코끼리와의 형제애를 저버리는 일 역시 없을 것이다. 하지만 쿠이족은 가난하고 제대로 된 교육을 받지 못했다는 이유로 반론의 기회조차 없이 코끼리를 학대했다는 혐의를 받아왔다. 이런 이유로 마을사람들은 나를 수린 지방행정부와 정부에서 고용된 사람으로 오해하고 내 말을 믿지 않았다. 그래서 초기에는 작업이 쉽지 않았는데, 나의 건축이 그들을 위한 것이며 그들의 삶을 바꿀 수 있다는 걸 증명하는 데 5년이 넘게 걸렸다. 최근 코로나바이러스감염증-19의 확산을 계기로 이 지역은 관광 명소가 되었다. 태국내 주요 관광지에 문을 닫으라는 지시가 내려지고 이곳에 코끼리들의 보금자리가 생겼다는 사실이 알려지면서, 관광업에 종사하던 천 마리 이상의 코끼리들이 전국 각지에서 반타클랑으로 돌아오기 시작했다. 쿠이 마을로 자본이 유입되자 수린 지방행정부는 입장료 수익으로 코끼리에게 봉급을 지급할 수 있게 되었다. 동시에 지방행정부는 지역 인근에 호텔이나 대형 건물 신축을 불허하는 대신 주민들의 집을 홈스테이나 작은 식당으로 개조하거나 기념품, 공예품, 커뮤니티 유튜브 채널을 만들어 지역경제를 활성화하고 자연환경과 문화, 쿠이족의 신앙을 보존하는 것을 장려했다. 일련의 과정을 겪으며 나는 ‘사람과 코끼리로부터 인류애를 배운다’는 귀중한 교훈을 얻었다. 가장 큰 감동은 이 코끼리들이 나를 기억한다는 점이다.

프렘타다: 엘리핀트 월드는 동물이 도시의 변화를 이끈 중요한 사례다. 이 프로젝트에서 건축은 사람들이 코끼리를 소중히 대하도록 돕는 한편 마을경제의 부흥을 위해 만들어졌다. 인간의 삶의 질에 대한 기준이 높아지는 만큼 코끼리의 삶의 질 또한 높아져야 한다. 이와 같이 사람과 코끼리(자연)가 공존하는 건축이 계속될수록 코끼리의 생존에도 청신호가 켜질 것이다.

프렘타다: 나에게 건축이란 트렌드에 구속받지 않는 예술이다. 모든 것은 이유와 필요에 의해 만들어진다. 많은 사람들이 내가 그들보다 “기준치가 낮고 규제가 적은 나라에서 일해 운이 좋다”고 이야기하지만 사실 굉장히 많은 제약에 맞서야 한다. 숙련도가 낮은 노동자들, 제한된 예산과시간, 지역성에 대한 지각과 열정, 권력자들의 태도와 같은 것들 말이다. 이러한 불리한 요소들은 내가 모든 면에 더 깊은 주의를 요하게 만든다. 복싱에 비유하면 어떤 규칙도 링도 없는 상태에서 싸우는 복서와 같다고 할까? 따라서 스스로 강해지려고 하며 내 생각에 진심으로 다가가려 하는 태도가 중요한 것 같다. 강인함은 내가 가진 유일한 무기다.

프렘타다: 나는 줄곧 태국에서 건축을 공부했는데 이것이 오히려 장점이 되었다. 덕분에 내 생각이 해외 학교에서 가르치는 사상과 섞이지 않고 그들의 영향에서 자유로울 수 있었다. 나는 두 명의 직원과 함께 작은 스튜디오를 운영하고 있다. 이러한 환경은 내게 생각의 자유를 주고 끊임없이 새로운 방향을 향해 나아가는 동력이 된다. 큰 회사에서 일하는 것과는 완전히 다른 것 같다. 스스로 평하자면 아름답고 자연스럽게 피어나는 야생화라고 부르고 싶다.

Bangkok Project Studio_ Boonserm Premthada

ARCHITECTURE, CONNECTING NATURE WITH THE HUMAN

Boonserm Premthada was born and raised in

Bangkok, Thailand. He received his Bachelor of Fine Arts (interior design) with

first class honors in 1988 and Master of Architecture from Chulalongkorn

University in 2002 and established his office named Bangkok Project Studio in

2003. He believes that architecture is the physical creation of an atmosphere

that serves to heighten man's awareness of his natural surroundings. His work is

not about designing a building, but rather about the manipulation of light,

shadow, wind, sound, and smells creating a 'poetics in architecture' that is a

living through sense. Beyond the realms of theory and practice, his work also

carries a strong socio-economic and cultural agenda as many of his projects

have associated social programs that aim to improve the lives of the

underprivileged.

Boonserm Premthada (Premthada): The government of Surin Provincial Administrative Organization (Surin PAO) invited me to be the project's architect. In Thailand, elephants differ in status from ordinary animals. Elephants also participate in royal ceremonies as sacred participants and are mobilized in various forms for long-distance travel, on construction sites, and in wars. People in Thailand consider elephants as part of their 'family', equivalent to people, not as pets or laborers. The Kui Village is one of the leading elephant habitats in Thailand. For centuries, people in this area have lived with elephants all their lives from birth to death. However, as industrialization accelerated and machines replaced elephants, elephant and elephant owners were left destitute enough to beg for money or leave for other locations such as Bangkok, Chiang Mai and Phuket and seek work in the forest. The project's goal was to apply for a government budget to save and rebuild the area, to settle elephant and elephant keepers in the village, to discuss elephant abuse, and to promote the restoration of forests to revive sources of elephant food and water.

Premthada: The Kui village is a village of elephant keepers more than 400 years old. There is a Pa A-Jiang temple in the village that performs religious ceremonies for both people and elephants. Elephant cemeteries are part of this temple, and when elephants die, they are buried here. There are young veterinarians who specialize in elephant care at elephant hospitals. A series of facilities have been in place even before the start of Elephant World. The project aims to create an economically self-sufficient community by first by preserving culture, second by restoring forests for feeding elephants and growing medicinal herbs, and finally by continuing to attract tourism respecting the elephant and Kui people's lifestyles. Soon, elephants from all over Thailand will gather here, floating in cities.

Premthada: I tried to focus on elephants because I have long been designing human-centered architecture. Zoos are spaces for the purpose of separating humans from animals and displaying the lived experiences and behaviors of animals. However, I wanted to learn how humans coexist with large animals in nature through 'Architecture for Elephants', and to learn how to recognize and sympathize with the values of humans and other creatures. The Kui people live for the elephants, and the elephants live for the Kui people. Therefore, Elephant World reflects 'love', the fundamental mindset of the village people who are fostering deep ties with elephants. The government pays the elephants that the Kui people are taking care of, but when the elephants die, their owners are not paid. So, the Kui people give each elephant a name and care for it like their own children. When they have nothing to eat, they take the elephant's food first, even if they starve. Its architecture emphasizes the depth of this connection between humans and elephants and serves as a link to strengthen these relationships.

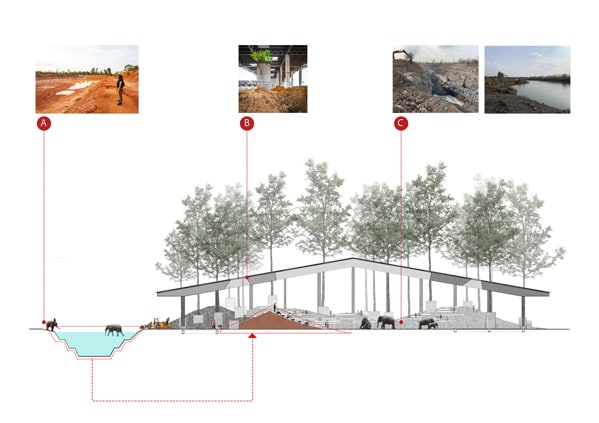

Premthada: In the past, investors damaged the forests and encroached upon land to grow cash crops in the national forests here. As a result, the Surin region suffered the most severe drought in Thailand due to water shortages and the year-round extremes in heat. As it takes a long time to restore the forest to its former health, we chose to make the most of existing resources to build buildings. I dug a rainwater pond and made bricks from the soil and used it as material for major buildings, including the amphitheaters. The pond has become a source of nutrients for forests, elephants, and people. The new brick observatory will also help restore the forest by climbing on top of it and spreading the seeds of local vegetation to the surrounding area in the wind.

Premthada: Surin PAO had already had master plans and completed the design and construction of several buildings before I joined the project. I considered the elephant 'walkway' from the village to the three buildings as a key concept in the layout. The Brick Observation Tower is placed at the highest level of land and the Elephant Museum at the lowest level, and the two are divided into the Cultural Courtyard. All three buildings lead to surrounding forests and ponds, and the height, openness, and appearance of the building gradually decreasing are combined with the surrounding area to form part of the landscape.

Premthada: The Cultural Courtyard is a place for village-specific religious and cultural events long held by villagers. Traditional rituals of the Kui people and events were originally held at home with relatives, neighbors, and elephants. The courtyard, where these events are held, contains the meaning of a huge elephant house where visitors can join and witness the daily lives of the Kui people.

Premthada: It is so amazing that more than 200 elephants lived in homes of people with large open spaces in the middle of the forest. By integrating the scales of places, people, and elephants here, the buildings become part of a familiar landscape, I sought to find a balance between the elephants and people and reduce the proportion of ‘people-oriented'. To this end, the way I interpreted this was to minimize the construction work and to secure as much space as possible. The Elephant Playground was designed to allow people to adapt to the daily rhythms of elephants. Open spaces, piles of dirt, and trees, as well as roofs without walls, are familiar structures to elephants. Elephants, like us, have feelings, parents, and relatives. I thought that the priority was to create a 'not cold' space of familiar forms and materials to provide elephants with a comfortable environment. The soil on the ground is for elephants, and the basalt amphitheater is for humans. Both materials are readily available in the region. Since elephants know that they cannot climb rocks by instinct, they have distinguished boundaries through materials to harmonize with the environment.

Premthada: The Cultural Courtyard is a place in which elephants take walks and exercise to maintain their mental and physical health after eating and drinking, and where they relieve stress accumulated while staying at home for a long time. I thought both the amphitheater and the water space were necessary. Since it is a project carried out through tax money, the key was to solve the two simultaneously by using existing resources as much as possible. Ifa total of 8,600m3 of soil is dug up and a pond is built on the site, 207 elephants will have enough water for a month. In fact, I only designed half of the building. The other half is the work of nature, elephants, and the Kui people.

Premthada: The museum has designed visitors to encounter unexpected spaces. It's like entering the Kui village without knowing anything and finding elephants, or like walking in the woods and running into elephants. I also wanted to design this place to be a museum in the oral tradition, where the Kui people and elephants could possess and talk about their history themselves. I wanted them to talk about their lives and the 400-year history of the the Kui people, recounting their happiness, pain, and hardship, including the situation of being displaced, struggling to survive, criticism from foreigners, returning home, and shouting for pride and strength in their way of life. The Kui people have never had a chance to talk about their lives. The 'sound' inside the museum amplifies the echo of the wall with different heights. The poetic element here is the sound of elephants, the language of sensation, not the functional language of humans. The sound of elephants and their voice will be settled in the hearts of listeners with the sound of 'truth' emerging from the other side.

Premthada: The design of the museum attended to the creation of a space in which the interior and exterior coexist. The main passage leads to a chamber inside the museum and leads to four entrances that are connected outside the building. These entrances lead to different passages surrounding villages, ponds, forests, and buildings, respectively. The inner exhibition room where visitors stay is surrounded by a courtyard twice the museum's indoor exhibition area. The courtyard contains a unique atmosphere created by sunlight, rain, shadows, wind, and natural sounds of the actual place, and all these spaces are covered by brick walls. Through my design, I tried to wake up all the human senses about the story of the Kui people and the elephant. Of course, due to the solid red brick walls that surround the building and connect it with the landscape to create unity, the visibility into other areas may be reduced. The elephants walking into the museum will give a sense of space as if they were outside.

Premthada: I wanted people to spend as much time as possible inside this small structure and to experience different moods depending on the time slot or height. As people go up the stairs, they will realize that they don't have to run to the top like other observatories, realizing that the observation tower is all facing different directions from floor to floor. Here people will have time to slowly discover small and delicate things and reflect on themselves.

Premthada: The Brick Observation Tower is located on the border of well-preserved and damaged forests. It also helps to restore the forest. At the top of the observation tower, it winds at 29 - 38 km per hour, and seeds of several plants will be transported and scattered within a radius of 20m of the observation tower. In this sense, the observation tower can also be called the 'first tree' that produces the lives of other trees in the once-destroyed area. This tower was originally designed to help people avoid the body during the elephant's rut. It is the only building in Elephant World that cannot be entered by elephants, and it was designed as an engineering structure with indoor space, ventilation, and landscaping functions.

Premthada: The Kui people are poor, but money cannot seduce them. They will not sell elephants for the promise of financial gain like their parents or grandparents did. Nor will they betray their brotherhood with elephants by accepting offers from companies or organizations that want to make donations using their names. However, the Kui people have been accused of abusing elephants without the opportunity to argue their case because they are poor and poorly educated. For this reason, the villagers misunderstood me as a local administrative and government employee and did not believe me. So, it was not easy to work in the beginning and it took more than five years to prove that my architecture is for them and that it could change their lives. With the recent spread of the Coronavirus Disease-19 pandemic, the area has become a tourist attraction. After instructions were issued to close major tourist attractions in Thailand and it has been revealed that there is a home for elephants here, more than a thousand elephants from all over the country began to return to Ban Ta Klang. With the influx of capital into the Kui village, Surin PAO can pay the elephants from the proceeds of admission fees. At the same time, Surin PAO did not allow new hotels or large buildings near the area, but instead encouraged residents to convert their homes into homestays or small restaurants or create souvenirs, crafts, and YouTube channels as a community to boost the local economy and preserve local environment and cultural beliefs of the Kui. Through a series of encounters, I learned a valuable lesson from them: 'Learning humanity from people and elephants'. The greatest impression is that these elephants remembered me.

Premthada: Elephant World is an example of animals leading the changes in cities. In this project, architecture was built to help people cherish elephants while simultaneously reviving the village economy. If the standard for human quality of life increases, the quality of life for elephants should also increase accordingly. As such, the more human-elephant architecture continues, the greener lights will be trained on the elephant's survival.

Park: When I see Elephant World and your

other works such as The Artisans Ayutthaya (2017) and The Walk (2020), I know

you understand how art can be connected to architecture.

Premthada: To me, architecture is an art that is not bound by trends. Everything is made for reasons and need. Many people say that I am lucky to work in a country with lower standards and fewer regulations than them, but in fact, I must face a lot of restrictions such as low-skilled workers, limited budgets and time, the perception of and enthusiasm for locality, and the attitudes of powerful people. These unfavorable factors require more attention from me in every aspect. Compared to boxing, this is like a boxer who fights without any rules and a boxing ring. Therefore, I think it is important to try to be strong on my own and approach it sincerely. Strength is the only weapon I have.

Park: You are promoting Thai architecture

based on your work through seminars and forums held not only in Thailand but

also internationally. I think this discussion is important in finding the

identity of the country's architecture and strengthening its foundation, and

not one limited to individual work.

Premthada: I studied architecture in Thailand and graduated, which became an advantage. Thanks to this, my thoughts were not mixed with the ideas taught in overseas schools and I could be free from their influence. I am setting up a small studio with two employees. This working environment gives me freedom of thought and allows me to constantly move in new directions. It seems completely different from working for a big company. To make a self-review, I would call myself a wildflower which blooms beautifully and naturally.

자연과 인간을 연결하는 건축

분섬 프렘타다는 태국 방콕에서 태어나고 성장했다. 태국의 출라롱콘

대학교에서 인테리어 디자인을 전공(1988)하고 건축학 석사학위

(2002)를 받은 뒤 2003년에 방콕 프로젝트 스튜디오를 설립했다. 그는 건축이 자연에 대한 인간의 인식을 높이는 물리적 환경을 창조하는 일이라는 신념을 가지고 빛, 그림자, 바람, 소리, 냄새의 감각적 경험이 살아있는 ‘건축 시학’을 추구한다. 소외된 사람들의 삶을 개선하는 여러 프로젝트를 선보인

그의 작업은 이론과 실천을 아우르며 사회, 경제, 문화적

의제들을 다룬다.

건축은 인간의 필요에 의해 시작되었지만 건축이 높이는 장소는 늘 자연이었다. 우리는

인간 중심의 건축에 익숙해졌지만, 건축은 결국 자연에서 벗어날 수 없다. 그렇다면 주어진 환경을 개선하고 주변과 화합하는 건축이야말로 앞으로 절실하게 필요한 건축의 방향이 아닐까? 이러한 생각을 확장해 나가는 태국 건축가 분섬 프렘타다(방콕 프로젝트

스튜디오 대표)와 그의 대표작 ‘엘리펀트 월드’(2020)를 중심으로 이야기를 나누었다.

박창현(박): 태국 북동부

수린 주(州) 반타클랑에 위치한 엘리핀트 월드는 코끼리와

코끼리를 사육하는 쿠이(Kui)족의 삶의 터전을 10년에

걸쳐 조성한 프로젝트다. 코끼리와 사람이 공존하는 건축이라는 점에서 호기심을 자극한다. 프로젝트가 시작된 배경과 진행 과정이 궁금하다.

분섬 프렘타다(프렘타다): 수린 지방행정부에서 담당 건축가로 초청해 이 프로젝트에 참여하게 되었다. 태국에서 코끼리는 일반적인 동물과 위상이 다르다. 성스러운 대상으로 왕실 의식에 참여하기도 하며 장거리 이동, 건설 현장, 전쟁 둥에 다양한 형태로 동원되기도 했다. 태국사람들은 코끼리를 반려동물이나 노동력이 아닌 사람과 동등한 ‘가족’으로 여긴다. 쿠이 마을은 태국 내에서도 손꼽히는 코끼리 주요 서식지이다. 수세기 동안 이 지역 사람들은 태어나서 죽을 때까지 일생을 코끼리와 함께 살아왔다. 하지만 산업화가 가속되고 코끼리의 자리를 기계가 대체하면서 코끼리와 코끼리 사육사들은 돈을 구걸하거나 숲에서 일거리를 얻기 위해 방콕, 치앙마이, 푸켓 등타지로 떠나야 했다. 정부예산을 받아 이 지역을 되살리고 재건하기 위해 코끼리와 코끼리 사육사를 이 마을에 정착시켜 동물학대 문제를 논의하고, 숲을 복원해 코끼리들의 먹이와 수원을 되살리는 것이 프로젝트의 주된 목표였다.

박: 프로젝트가 쿠이 마을, 코끼리

병원, 사람과 코끼리 모두를 위한 사찰과 묘지까지 포괄하여, ‘사람과

코끼리가 함께 커뮤니티를 형성한다’는 점이 매우 흥미롭다.

프렘타다: 쿠이 마을은 400년 이상 된 코끼리 사육사들의 마을이다. 마을에는 사람과 코끼리 모두를 위한 종교의식을 행하는 파아지앙 사원이 있다. 코끼리묘지는 이 사원의 일부로 코끼리들이 죽으면 이곳에 묻힌다. 코끼리 병원에서는 코끼리만 전문적으로 진료하는 젊은 수의사들이 있다. 일련의 시설들은 엘리펀트 월드를 시작하기 전부터 원래 있던 것들이다. 이 프로젝트의 목표는 첫째로 지역 문화 보존, 둘째로 코끼리들의 먹이와 약초재배를 위한 숲의 복원, 마지막으로 코끼리와 쿠이족의 생활양식을 존중하는 관광사업을 꾸준히 유치해 경제적으로 자급자족할 수 있는 커뮤니티를 형성하는 것이다. 머지않아 여러 도시에서 떠돌고 있는 태국전역의 코끼리들이 이곳으로 모이게 될 것이다.

박: 공간의 초점을 코끼리, 코끼리 사육사, 관광객 중 어디에 맞추느냐에 따라서 이곳에서 느끼게 될 경험은 매우 달라질 것이라 생각한다. 일반적인 동물원이나 코끼리 체험 관광시설과의 차이점은 무엇인가?

프렘타다: 나는 지금껏 인간 중심의 건축을 해왔기 때문에 이번에는 코끼리에 초점을 맞추려고 했다. 동물원은 인간과 동물을 분리하고 동물들의 삶을 진열하기 위한 공간이다. 하지만 나는 ‘코끼리를 위한 건축’을 통해 인간이 자연 속에서 큰 동물과 공존하는 법을 배우고, 인간을 비롯한 다른 생명체들의 가치를 인지하고 공감하는 법을 알리고자 했다. 쿠이족은 코끼리를 위해 살고, 코끼리들은 쿠이족을 위해 산다. 따라서 엘리펀트 월드는 코끼리와 유대를 만들어가고 있는 마을 사람들의 마음가짐인 ‘사랑'을 반영한다. 정부는 쿠이족이 돌보고 있는 코끼리에게 봉급을 주는데, 코끼리가 죽으면 그 주인은 봉급을 받지 못한다. 그래서 쿠이족사람들은 코끼리에게 각각 이름을 붙여주고 제자식처럼 아끼고 돌본다. 심지어 먹을 것이 없을 때에도 자신들은 굶을지 언정 코끼리의 먹이를 먼저 챙길 정도다. 이곳의 건축은 인간과 코끼리 사이의 배려를 강조하며 이들의 관계를 강화하는 연결고리 역할을 한다.

박: 과거에 무성했던 숲을 복원해 거주환경에 도움을 주겠다는 발상은 자연 친화적인 동시에 인본 주의적이어서 공감된다. 매우 건조한 지역으로 보이는데 이곳 기후의 특징은 무엇인가?

프렘타다: 과거에 투자자들은 이곳의 국유림에 환금작물을 재배하기 위해 숲을 훼손하고 땅을 잠식했다. 그 결과 수린 지역 일대는 물부족으로 태국에서도 가장 극심한 가뭄을 겪었고 1년내내 무더위에 시달려야 했다. 숲을 복원하는 데 긴 시간이 걸리기 때문에 건물을 지으면서 기존 자원을 최대한 활용하는 방식을 택했다. 빗물 집수용 연못을 파고, 여기에서 나온 흙을 이용해 벽돌을 만들어 원형극장을 비롯한주요 건물들의 자재로 사용했다. 연못은 숲과 코끼리, 사람들에게 영양을 공급하는 수원이 되었다. 벽돌전망대는 그 위에 올라 지역 식생의 씨앗을 바람을 타고 주변으로 퍼뜨리는 역할을 함으로써 숲의 복원에도 힘을 보탤 것이다.

박: 문화마당, 코끼리박물관, 벽돌전망대를 설계하면서 지형이나 기존건물들과 어떤 관계를 맺도록 고려했나?

프렘타다: 내가 프로젝트에 참여하기 전에 수린 지방행정부에서 이미 마스터플랜을 세우고 몇몇 건물의 설계와 시공을 완료한 상태였다. 나는 마을에서 출발해 세 건물로 이어지는 코끼리 ‘산책로’를 배치의 핵심 개념으로 생각했다. 대지 레벨이 가장 높은 곳에 벽돌전망대를, 가장 낮은 곳에 코끼리박물관을 두고 이 둘을 문화마당으로 구분했다. 세 건물 모두 주변의 숲과 연못으로 이어지며, 점차 낮아지는 건물의 높이와 개방성, 외형은 주변과 어우러져 풍경의 일부가 된다.

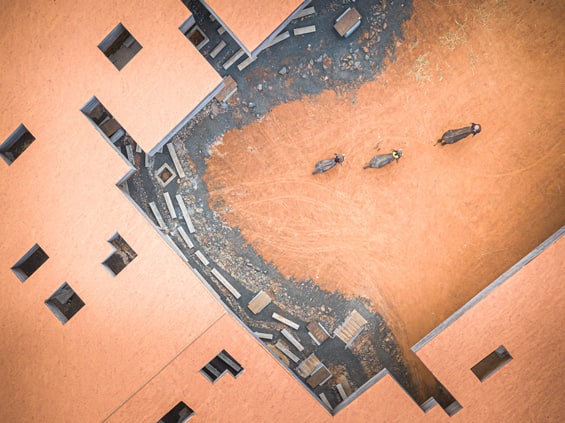

박: 문화마당은 口자 형태의 지붕으로 덮여 있다. 수평적으로 뻗은 구조는 시각적으로 강한 인상을 준다. 언덕으로 둘러싸인 넓은 마당 안에서는 어떤 행위가 일어나는가?

프렘타다: 문화마당은 마을사람들이 오랫동안 행해온 마을 고유의 신앙과 문화와 관련된 행사를 위한 공간이다. 쿠이족의 전통 의례와 행사들은 원래 친척과 이웃, 코끼리들이 다같이 모여 집에서 치러졌다. 이런 행사들이 열리는 문화마당은 관람객들이 여기에 동참하고 쿠이족의 일상을 목격할 수 있는 거대한코끼리 집의 의미를 담고 있다.

박: 코끼리와 사람 모두를 위한공간이기 때문에 건물의 스케일에 대해 고민이 컸을 것 같다. 코끼리와 사람, 이 둘사이에서 어떤 방식으로 균형을 찾았나? 또한 안전을 위한 영역 분리는 어떻게 이루어지나?

프렘타다: 숲 한 가운데 넓은 공터를 가진 사람들의 집에서 200마리가넘는 코끼리들이 함께 살고 있다는 사실이 너무 놀라웠다. 이곳의 장소, 사람, 코끼리의 스케일을 통합하여 건물이 익숙한 풍경의 일부가 되게 함으로써 둘사이의 균형을 찾고 ‘자기 중심적인'사람의 비중을 낮추고자 했다. 이를 위해 내가 생각 한 방식은 구축 행위를 최소화하고 열린 공간을 가급적 그대로 남기는 것이다. 문화마당은 사람들이 코끼리의 일상에 적응할 수 있도록 계획됐다. 흙으로 덮인 곳은 코끼리를 위한 영역이고 현무암으로 만든 원형극장은 사람을 위한 영역이다. 둘 다 지역에서 쉽게 구할 수 있는 재료다. 코끼리는 본능적으로 바위에 오를 수 없다는 것을 알고 있기 때문에 재료로 경계를 구분하고 환경과도 조화를 이루도록 했다. 벽이 없이 지붕만 있는 열린 공간, 흙 더미와 같이 친숙한 형태와 재료로 ‘차갑지 않은 공간’을 조성해 코끼리 에게 안락한 환경을 제공하는 것이 우선 과제라고 생각했다.

박: 문화마당의 바깥쪽은 평평하지 않고 굴곡진 흙 더미로 이루어져

코끼리들이 뒹굴 수 있다. 강이 4km 이상 떨어져 있기

때문에 코끼리들이 물장난을 할 영역이 필요했을텐데, 흙을 파서 언덕을 만들고 빗물을 모아 연못을 만든다는

아이디어는 어떻게 제안하게 되었나?

프렘타다: 문화마당은 코끼리가 먹고 마신 뒤 심신의 건강을 유지하기 위해 산책하고 운동하는 공간이자, 오래 집에 머무르며 쌓인 스트레스를 해소하는 공간이다. 나는 원형극장과 수공간 두 가지가 모두 필요하다고 생각했다. 국민의 세금으로 진행되는 프로젝트이기 때문에 최대한 기존 자원을 활용해 이 둘을 동시에 해결하는 것이 관건이었다. 총 8,600m³의 흙을 파내고 그 자리에 연못을 조성하면, 207마리의 코끼리들이 한 달 동안 사용할 수 있는 충분한 물을 확보하게 된다. 실상 나는 건물의 절반만 설계했을 뿐이다. 나머지 반은 자연, 코끼리, 쿠이 마을사람들의 작업이라고 할 수 있다.

박: 코끼리박물관의 디자인은 구성적이며 사색적 감성을 불러일으킨다. 방금 살펴본 문화마당과는 전혀 다른 유형의 디자인인데, 특정 부족의 역사를 담은 프로젝트라는 점에서 특히 고려한 것은 무엇이었나?

프렘타다: 박물관에서 관람객들이 예상하지 못한 공간을 맞닥뜨리게 하고 싶었다. 아무것도 모르는 상태에서 쿠이족의 집 안으로 들어가 코끼리를 발견하거나, 숲 속을 걷다 우연히 코끼리를 마주치는 것처럼 말이다. 또한 나는 이곳을 쿠이족과 코끼리들 스스로 자신들의 역사를 이야기할 수 있는 구전(口傳) 형태의 박물관이 되도록 설계하고자 했다. 쿠이족은 지금까지 자신들의 삶에 대해 이야기할 기회가 없었다. 실향민이 된 처지, 생존을 위한 고군분투, 외지인들의 비난, 귀향, 삶의 방식에 대한 자부심과 힘에 대한 외침 등 행복과 고통, 고난이 깃든 400년 역사에 대해 스스로 말하기를 바랐다. 박물관안의 ‘소리’는 높낮이가 다른 벽을 타고 울림이 증폭된다. 여기서 시적인 요소는 인간의 기능적 언어가 아닌, 감각의 언어인 코끼리들의 소리이다. 코끼리도 우리처럼 감정을 가지고 있고, 부모와 친척도 있다. 코끼리 소리와 쿠이족의 음성은 다른 쪽에서 들려오는 ‘진실'의 소리로 듣는 이들의 마음속에 깊은 여운을 남길 것이다.

박: 당신의 설명에 따라 실제 공간을 상상해보니 코끼리와 인간, 건축이 만들어내는 공감각적 중폭이 와닿는 듯하다. 기하학적 구성을 가진 박물관은 그 자체로 완결된 독립적 형태를 띠고 있다. 이는 주변과의 관계에서 다소 폐쇄적일 수 있는 구조로 보이는데 대지의 맥락에 어떻게 대응하나?

프렘타다: 박물관 설계는 내부와 외부가 공존하는 공간을 창조하는 일이었다. 중앙통로는 박물관내부의 실로 연결되며 건물 바깥으로 연결된 네 개의 출입구로 이어진다. 이 출입구들은 각각마을, 연못, 숲과 건물을 둘러싼 다른 통로로 이어진다. 관람객이 머무는 내부전시실은 박물관 실내 전시 영역의 두 배에 이르는 안뜰로 둘러싸여 있다. 안뜰은 이 지역의 햇빛, 비, 그림자, 바람, 소리가 자아내는 독특한 분위기를 그대로 담고 있으며, 이 모든 공간을 벽돌벽이 층층이 감싸고 있다. 물론 건물을 에워싸고 풍경과 연결시켜 통일성을 만들어내는 단단한 붉은 벽돌 벽 때문에 다른 쪽의 시야가 줄어들 수도 있지만, 나의 디자인을 통해 쿠이족과 코끼리의 이야기에 대해 인간의 모든 감각을 깨우고자 노력했다. 박물관 안을 거니는 코끼리들은 외부에 있는 듯한 공간감을 선사할 것이다.

박: 벽돌전망대는 형태와 벽돌의 특징 등 재미있는 요소가 많다. 꼭대기층으로 올라가는 여정에서 층마다 다른 느낌을 줄 것 같은데 어떤 변화를 의도했나?

프렘타다: 나는 사람들이 이 작은 구조물 안에서 가능한 많은 시간을 보내고, 시간대나 높이에 따라 다른 분위기를 경험하길 바랐다. 사람들은 계단을 따라 위로 올라갈수록 전망대가 층별로 모두 다른 방향을 향하고 있음을 자각하면서 다른 전망대처럼 꼭대기로 달려갈 필요가 없음을 느낄 것이다. 시간을 두고 천천히 작고 섬세한 것들을 발견하며 자신을 성찰하는 시간을 보내게 될 것이다.

박: 벽돌전망대는 엘리펀트 월드 전체 배치에서 연결성을 지닌 특징적인 위치에 세워졌다. 이는 어떤 의도인가?

프렘타다: 전망대는 잘 보존된 숲과 훼손된 숲의 경계에 있다. 높이 솟은 전망대는 숲을 복원하는 데에도 일조한다. 전망대 꼭대기 부분에는 시속 29~38km의 바람이 부는데, 전망대 반경 20m안에 여러 식물의 씨앗을 운반해 흩뿌릴 것이다. 그런 의미에서 전망대는 한때 파괴되었던 지역에서 다른 나무들의 생명을 낳는 첫 번째 나무’라고도 할 수 있다. 원래 전망대는 코끼리들의 발정기 때 사람들이 몸을 피할 용도로 디자인된 구조물이었다. 엘리펀트 월드 안에서 유일하게 코끼리가 들어갈 수 없는 건물로, 그 자체로 실내 공간, 통풍 및 조경 기능을 갖춘 공학적 구조물로 설계됐다.

박: 정부의 예산으로 이러한 문화적, 역사적 배경을 가지고 있는 프로젝트를 진행하기가 쉽지 않았을 것 같다. 가장 어려웠던 문제는 무엇이었나?

프렘타다: 쿠이족은 가난하지만 돈으로 그들을 유혹할 수는 없다. 부모와 조부모 세대가 그러했듯 그들은 부를 위해 코끼리를 팔지 않을 것이다. 자신들의 이름을 내세워 기부하려는 기업이나 단체와 손잡고 코끼리와의 형제애를 저버리는 일 역시 없을 것이다. 하지만 쿠이족은 가난하고 제대로 된 교육을 받지 못했다는 이유로 반론의 기회조차 없이 코끼리를 학대했다는 혐의를 받아왔다. 이런 이유로 마을사람들은 나를 수린 지방행정부와 정부에서 고용된 사람으로 오해하고 내 말을 믿지 않았다. 그래서 초기에는 작업이 쉽지 않았는데, 나의 건축이 그들을 위한 것이며 그들의 삶을 바꿀 수 있다는 걸 증명하는 데 5년이 넘게 걸렸다. 최근 코로나바이러스감염증-19의 확산을 계기로 이 지역은 관광 명소가 되었다. 태국내 주요 관광지에 문을 닫으라는 지시가 내려지고 이곳에 코끼리들의 보금자리가 생겼다는 사실이 알려지면서, 관광업에 종사하던 천 마리 이상의 코끼리들이 전국 각지에서 반타클랑으로 돌아오기 시작했다. 쿠이 마을로 자본이 유입되자 수린 지방행정부는 입장료 수익으로 코끼리에게 봉급을 지급할 수 있게 되었다. 동시에 지방행정부는 지역 인근에 호텔이나 대형 건물 신축을 불허하는 대신 주민들의 집을 홈스테이나 작은 식당으로 개조하거나 기념품, 공예품, 커뮤니티 유튜브 채널을 만들어 지역경제를 활성화하고 자연환경과 문화, 쿠이족의 신앙을 보존하는 것을 장려했다. 일련의 과정을 겪으며 나는 ‘사람과 코끼리로부터 인류애를 배운다’는 귀중한 교훈을 얻었다. 가장 큰 감동은 이 코끼리들이 나를 기억한다는 점이다.

박: 건축가로서 이러한 태도와 교감이 중요하다고 생각한다. 태국에서 코끼리와 관련된 건축 프로젝트가 많아지리라 예상되는데, 앞으로 지어질 동물 관련 건축에 대한 관점을 이야기해 달라.

프렘타다: 엘리핀트 월드는 동물이 도시의 변화를 이끈 중요한 사례다. 이 프로젝트에서 건축은 사람들이 코끼리를 소중히 대하도록 돕는 한편 마을경제의 부흥을 위해 만들어졌다. 인간의 삶의 질에 대한 기준이 높아지는 만큼 코끼리의 삶의 질 또한 높아져야 한다. 이와 같이 사람과 코끼리(자연)가 공존하는 건축이 계속될수록 코끼리의 생존에도 청신호가 켜질 것이다.

박: 엘리핀트 월드를 비롯해 와인 아유타야(2017)나 더 워크(2020) 등 일련의 작업을 보면 예술이 건축으로 어떻게 연결될 수 있는지 다루고 있다는 생각이 든다.

프렘타다: 나에게 건축이란 트렌드에 구속받지 않는 예술이다. 모든 것은 이유와 필요에 의해 만들어진다. 많은 사람들이 내가 그들보다 “기준치가 낮고 규제가 적은 나라에서 일해 운이 좋다”고 이야기하지만 사실 굉장히 많은 제약에 맞서야 한다. 숙련도가 낮은 노동자들, 제한된 예산과시간, 지역성에 대한 지각과 열정, 권력자들의 태도와 같은 것들 말이다. 이러한 불리한 요소들은 내가 모든 면에 더 깊은 주의를 요하게 만든다. 복싱에 비유하면 어떤 규칙도 링도 없는 상태에서 싸우는 복서와 같다고 할까? 따라서 스스로 강해지려고 하며 내 생각에 진심으로 다가가려 하는 태도가 중요한 것 같다. 강인함은 내가 가진 유일한 무기다.

박: 당신은 국내의 세미나와 포럼에서 자신의 작업을 통해 태국 건축을 알리고 있다. 개인의 작업에 국한되지 않고, 자국 건축의 정체성을 찾아 그 기반을 탄탄히 다지는 데 있어서 이러한 논의는 중요하다고 생각한다.

프렘타다: 나는 줄곧 태국에서 건축을 공부했는데 이것이 오히려 장점이 되었다. 덕분에 내 생각이 해외 학교에서 가르치는 사상과 섞이지 않고 그들의 영향에서 자유로울 수 있었다. 나는 두 명의 직원과 함께 작은 스튜디오를 운영하고 있다. 이러한 환경은 내게 생각의 자유를 주고 끊임없이 새로운 방향을 향해 나아가는 동력이 된다. 큰 회사에서 일하는 것과는 완전히 다른 것 같다. 스스로 평하자면 아름답고 자연스럽게 피어나는 야생화라고 부르고 싶다.

Bangkok Project Studio_ Boonserm Premthada

ARCHITECTURE, CONNECTING NATURE WITH THE HUMAN

Boonserm Premthada was born and raised in

Bangkok, Thailand. He received his Bachelor of Fine Arts (interior design) with

first class honors in 1988 and Master of Architecture from Chulalongkorn

University in 2002 and established his office named Bangkok Project Studio in

2003. He believes that architecture is the physical creation of an atmosphere

that serves to heighten man's awareness of his natural surroundings. His work is

not about designing a building, but rather about the manipulation of light,

shadow, wind, sound, and smells creating a 'poetics in architecture' that is a

living through sense. Beyond the realms of theory and practice, his work also

carries a strong socio-economic and cultural agenda as many of his projects

have associated social programs that aim to improve the lives of the

underprivileged.

Architecture finds its origin in human

needs, but the realm in which architecture is placed is always nature. We have

become accustomed to human-centered architecture, but architecture cannot

escape nature after all. Then, is it not architecture that improves the given

environment and harmonizes with the surroundings? Is this not the architectural

direction that is desperately needed in the future? I spoke with the Thai

architect Boonserm Premthada (principal, Bangkok Project Studio) who is

expanding upon this idea, around his representative work, Elephant World

(2020).

Park Changhyun (Park): Elephant World,

which is in Ban Ta Klang, Surin Province, northeastern Thailand, is a project

that has for over a decade created a place of life for elephants and the Kui

people who raise elephants. It stimulates curiosity in that it is an

architecture in which elephants and humans can coexist. I am curious about the

background and progress of this project.

Boonserm Premthada (Premthada): The government of Surin Provincial Administrative Organization (Surin PAO) invited me to be the project's architect. In Thailand, elephants differ in status from ordinary animals. Elephants also participate in royal ceremonies as sacred participants and are mobilized in various forms for long-distance travel, on construction sites, and in wars. People in Thailand consider elephants as part of their 'family', equivalent to people, not as pets or laborers. The Kui Village is one of the leading elephant habitats in Thailand. For centuries, people in this area have lived with elephants all their lives from birth to death. However, as industrialization accelerated and machines replaced elephants, elephant and elephant owners were left destitute enough to beg for money or leave for other locations such as Bangkok, Chiang Mai and Phuket and seek work in the forest. The project's goal was to apply for a government budget to save and rebuild the area, to settle elephant and elephant keepers in the village, to discuss elephant abuse, and to promote the restoration of forests to revive sources of elephant food and water.

Park: It is very interesting that the project covers the Kui village, elephant hospitals, temples, and cemeteries for both people and elephants, and that 'people and elephants form a community together'.

Premthada: The Kui village is a village of elephant keepers more than 400 years old. There is a Pa A-Jiang temple in the village that performs religious ceremonies for both people and elephants. Elephant cemeteries are part of this temple, and when elephants die, they are buried here. There are young veterinarians who specialize in elephant care at elephant hospitals. A series of facilities have been in place even before the start of Elephant World. The project aims to create an economically self-sufficient community by first by preserving culture, second by restoring forests for feeding elephants and growing medicinal herbs, and finally by continuing to attract tourism respecting the elephant and Kui people's lifestyles. Soon, elephants from all over Thailand will gather here, floating in cities.

Park: I think the experience varies greatly depending on whether you focus the space on elephants, elephant keepers or tourists. What is the difference between a typical zoo or facilities for elephant tourism?

Premthada: I tried to focus on elephants because I have long been designing human-centered architecture. Zoos are spaces for the purpose of separating humans from animals and displaying the lived experiences and behaviors of animals. However, I wanted to learn how humans coexist with large animals in nature through 'Architecture for Elephants', and to learn how to recognize and sympathize with the values of humans and other creatures. The Kui people live for the elephants, and the elephants live for the Kui people. Therefore, Elephant World reflects 'love', the fundamental mindset of the village people who are fostering deep ties with elephants. The government pays the elephants that the Kui people are taking care of, but when the elephants die, their owners are not paid. So, the Kui people give each elephant a name and care for it like their own children. When they have nothing to eat, they take the elephant's food first, even if they starve. Its architecture emphasizes the depth of this connection between humans and elephants and serves as a link to strengthen these relationships.

Park: The idea of restoring forests that were once rich and verdant is driven by the hope of helping the living environment, one both nature-friendly and humanistic, and so it is sympathetic. It seems like a very dry place, what are the characteristics of the climate there?

Premthada: In the past, investors damaged the forests and encroached upon land to grow cash crops in the national forests here. As a result, the Surin region suffered the most severe drought in Thailand due to water shortages and the year-round extremes in heat. As it takes a long time to restore the forest to its former health, we chose to make the most of existing resources to build buildings. I dug a rainwater pond and made bricks from the soil and used it as material for major buildings, including the amphitheaters. The pond has become a source of nutrients for forests, elephants, and people. The new brick observatory will also help restore the forest by climbing on top of it and spreading the seeds of local vegetation to the surrounding area in the wind.

Park: When designing the Cultural Courtyard (so-called Elephant Playground), the Elephant Museum, and the Brick Observation Tower, how did you consider relating them to the terrain and existing buildings?

Premthada: Surin PAO had already had master plans and completed the design and construction of several buildings before I joined the project. I considered the elephant 'walkway' from the village to the three buildings as a key concept in the layout. The Brick Observation Tower is placed at the highest level of land and the Elephant Museum at the lowest level, and the two are divided into the Cultural Courtyard. All three buildings lead to surrounding forests and ponds, and the height, openness, and appearance of the building gradually decreasing are combined with the surrounding area to form part of the landscape.

Park: The Cultural Courtyard is covered with a roof over both wings. The horizontally stretched structure gives a strong visual impression. What happens in this large yard surrounded by the hills?

Premthada: The Cultural Courtyard is a place for village-specific religious and cultural events long held by villagers. Traditional rituals of the Kui people and events were originally held at home with relatives, neighbors, and elephants. The courtyard, where these events are held, contains the meaning of a huge elephant house where visitors can join and witness the daily lives of the Kui people.

Park: Since it is a space for both elephants and people, I think you must have been worried about the scale of the building. How do you find a balance between an elephant and a person? Also, how is the area separation performed to ensure safety?

Premthada: It is so amazing that more than 200 elephants lived in homes of people with large open spaces in the middle of the forest. By integrating the scales of places, people, and elephants here, the buildings become part of a familiar landscape, I sought to find a balance between the elephants and people and reduce the proportion of ‘people-oriented'. To this end, the way I interpreted this was to minimize the construction work and to secure as much space as possible. The Elephant Playground was designed to allow people to adapt to the daily rhythms of elephants. Open spaces, piles of dirt, and trees, as well as roofs without walls, are familiar structures to elephants. Elephants, like us, have feelings, parents, and relatives. I thought that the priority was to create a 'not cold' space of familiar forms and materials to provide elephants with a comfortable environment. The soil on the ground is for elephants, and the basalt amphitheater is for humans. Both materials are readily available in the region. Since elephants know that they cannot climb rocks by instinct, they have distinguished boundaries through materials to harmonize with the environment.

Park: The outside of the large yard is not flat but consists of a curved pile of earth, allowing elephants to roll around. Since the river is more than four kilometers away, elephants need an area to play with water, so how did you come up with the idea of digging up soil, making hills, collecting rainwater, and making ponds?

Premthada: The Cultural Courtyard is a place in which elephants take walks and exercise to maintain their mental and physical health after eating and drinking, and where they relieve stress accumulated while staying at home for a long time. I thought both the amphitheater and the water space were necessary. Since it is a project carried out through tax money, the key was to solve the two simultaneously by using existing resources as much as possible. Ifa total of 8,600m3 of soil is dug up and a pond is built on the site, 207 elephants will have enough water for a month. In fact, I only designed half of the building. The other half is the work of nature, elephants, and the Kui people.

Park: The design of the Elephant Museum is very constructive and evokes thoughtful sensibilities. It seems to be a completely different type of design from the courtyard we just observed. What was more considered in terms of a project that contained the history of a particular tribe?

Premthada: The museum has designed visitors to encounter unexpected spaces. It's like entering the Kui village without knowing anything and finding elephants, or like walking in the woods and running into elephants. I also wanted to design this place to be a museum in the oral tradition, where the Kui people and elephants could possess and talk about their history themselves. I wanted them to talk about their lives and the 400-year history of the the Kui people, recounting their happiness, pain, and hardship, including the situation of being displaced, struggling to survive, criticism from foreigners, returning home, and shouting for pride and strength in their way of life. The Kui people have never had a chance to talk about their lives. The 'sound' inside the museum amplifies the echo of the wall with different heights. The poetic element here is the sound of elephants, the language of sensation, not the functional language of humans. The sound of elephants and their voice will be settled in the hearts of listeners with the sound of 'truth' emerging from the other side.

Park: I haven't been there myself, but if l imagines what you mention here, I can feel the synesthetic amplification created by elephants, humans, and architecture itself. The museum with its geometric composition has its own completely independent form. It appears to be a somewhat closed structure in connection with or in relationships with the surrounding world, how does the museum correspond to the context of the site?

Premthada: The design of the museum attended to the creation of a space in which the interior and exterior coexist. The main passage leads to a chamber inside the museum and leads to four entrances that are connected outside the building. These entrances lead to different passages surrounding villages, ponds, forests, and buildings, respectively. The inner exhibition room where visitors stay is surrounded by a courtyard twice the museum's indoor exhibition area. The courtyard contains a unique atmosphere created by sunlight, rain, shadows, wind, and natural sounds of the actual place, and all these spaces are covered by brick walls. Through my design, I tried to wake up all the human senses about the story of the Kui people and the elephant. Of course, due to the solid red brick walls that surround the building and connect it with the landscape to create unity, the visibility into other areas may be reduced. The elephants walking into the museum will give a sense of space as if they were outside.

Park: There are many interesting elements such as the shape of the Brick Observation Tower and the characteristics of the brick. On the journey up to the top floor, I think it's going to feel different from floor to floor. What kind of changes did you hope to achieve?

Premthada: I wanted people to spend as much time as possible inside this small structure and to experience different moods depending on the time slot or height. As people go up the stairs, they will realize that they don't have to run to the top like other observatories, realizing that the observation tower is all facing different directions from floor to floor. Here people will have time to slowly discover small and delicate things and reflect on themselves.

Park: The Brick Observation Tower was built in a characteristic location to f form connections across Elephant World. What was your intention?

Premthada: The Brick Observation Tower is located on the border of well-preserved and damaged forests. It also helps to restore the forest. At the top of the observation tower, it winds at 29 - 38 km per hour, and seeds of several plants will be transported and scattered within a radius of 20m of the observation tower. In this sense, the observation tower can also be called the 'first tree' that produces the lives of other trees in the once-destroyed area. This tower was originally designed to help people avoid the body during the elephant's rut. It is the only building in Elephant World that cannot be entered by elephants, and it was designed as an engineering structure with indoor space, ventilation, and landscaping functions.

Park: With the government's budget, it would not have been easy to carry out projects of this cultural and historical background and scope. What was the most difficult challenge?

Premthada: The Kui people are poor, but money cannot seduce them. They will not sell elephants for the promise of financial gain like their parents or grandparents did. Nor will they betray their brotherhood with elephants by accepting offers from companies or organizations that want to make donations using their names. However, the Kui people have been accused of abusing elephants without the opportunity to argue their case because they are poor and poorly educated. For this reason, the villagers misunderstood me as a local administrative and government employee and did not believe me. So, it was not easy to work in the beginning and it took more than five years to prove that my architecture is for them and that it could change their lives. With the recent spread of the Coronavirus Disease-19 pandemic, the area has become a tourist attraction. After instructions were issued to close major tourist attractions in Thailand and it has been revealed that there is a home for elephants here, more than a thousand elephants from all over the country began to return to Ban Ta Klang. With the influx of capital into the Kui village, Surin PAO can pay the elephants from the proceeds of admission fees. At the same time, Surin PAO did not allow new hotels or large buildings near the area, but instead encouraged residents to convert their homes into homestays or small restaurants or create souvenirs, crafts, and YouTube channels as a community to boost the local economy and preserve local environment and cultural beliefs of the Kui. Through a series of encounters, I learned a valuable lesson from them: 'Learning humanity from people and elephants'. The greatest impression is that these elephants remembered me.

Park: If you deal with architecture of that attitude and communion, there will be more building projects related to elephants in Thailand. Could you tell us about your perspective on animal-related architecture to be built in the future?

Premthada: Elephant World is an example of animals leading the changes in cities. In this project, architecture was built to help people cherish elephants while simultaneously reviving the village economy. If the standard for human quality of life increases, the quality of life for elephants should also increase accordingly. As such, the more human-elephant architecture continues, the greener lights will be trained on the elephant's survival.

Park: When I see Elephant World and your

other works such as The Artisans Ayutthaya (2017) and The Walk (2020), I know

you understand how art can be connected to architecture.

Premthada: To me, architecture is an art that is not bound by trends. Everything is made for reasons and need. Many people say that I am lucky to work in a country with lower standards and fewer regulations than them, but in fact, I must face a lot of restrictions such as low-skilled workers, limited budgets and time, the perception of and enthusiasm for locality, and the attitudes of powerful people. These unfavorable factors require more attention from me in every aspect. Compared to boxing, this is like a boxer who fights without any rules and a boxing ring. Therefore, I think it is important to try to be strong on my own and approach it sincerely. Strength is the only weapon I have.

Park: You are promoting Thai architecture

based on your work through seminars and forums held not only in Thailand but

also internationally. I think this discussion is important in finding the

identity of the country's architecture and strengthening its foundation, and

not one limited to individual work.

Premthada: I studied architecture in Thailand and graduated, which became an advantage. Thanks to this, my thoughts were not mixed with the ideas taught in overseas schools and I could be free from their influence. I am setting up a small studio with two employees. This working environment gives me freedom of thought and allows me to constantly move in new directions. It seems completely different from working for a big company. To make a self-review, I would call myself a wildflower which blooms beautifully and naturally.