리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍_ 리얼리치 샤리프

전통과 기술의 접점을 탐구하다

리얼리치 샤리프는 2011년 리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍을 설립하여 지역성과

수공예를 강조하는 건축 활동을 이어가고 있다, 인도네시아 반둥 공과대학교를 졸업하고, 호주 뉴사우스웨일스 대학교에서 건축학석사 학위를 받았다, 이후 영국

포스터 앤드 파트너스와 싱가포르 디피아키텍츠에서 실무경력을 쌓았다, 2017년인도네시아 건축가협회 자카르타

어워드를 수상했으며, 직접 설립한 오마도서관을 통해 작가와 교육자로서 건축의 사회적 가치 실현에도 힘쓰고

있다.

박창현(박): 리얼리치

아키텍처 워크숍의 대표작인 ‘구하(Guba)’는 두 번의

리노베이션으로 완성된 프로젝트로, 시간이 지날수록 다양하게 바뀌어서 흥미롭다. 주택가 건물을 개조한 첫 번째 작업을 ‘길드(Guild)', 중개축한 두 번째 작업을 ‘구하’라고 이름 붙였다.

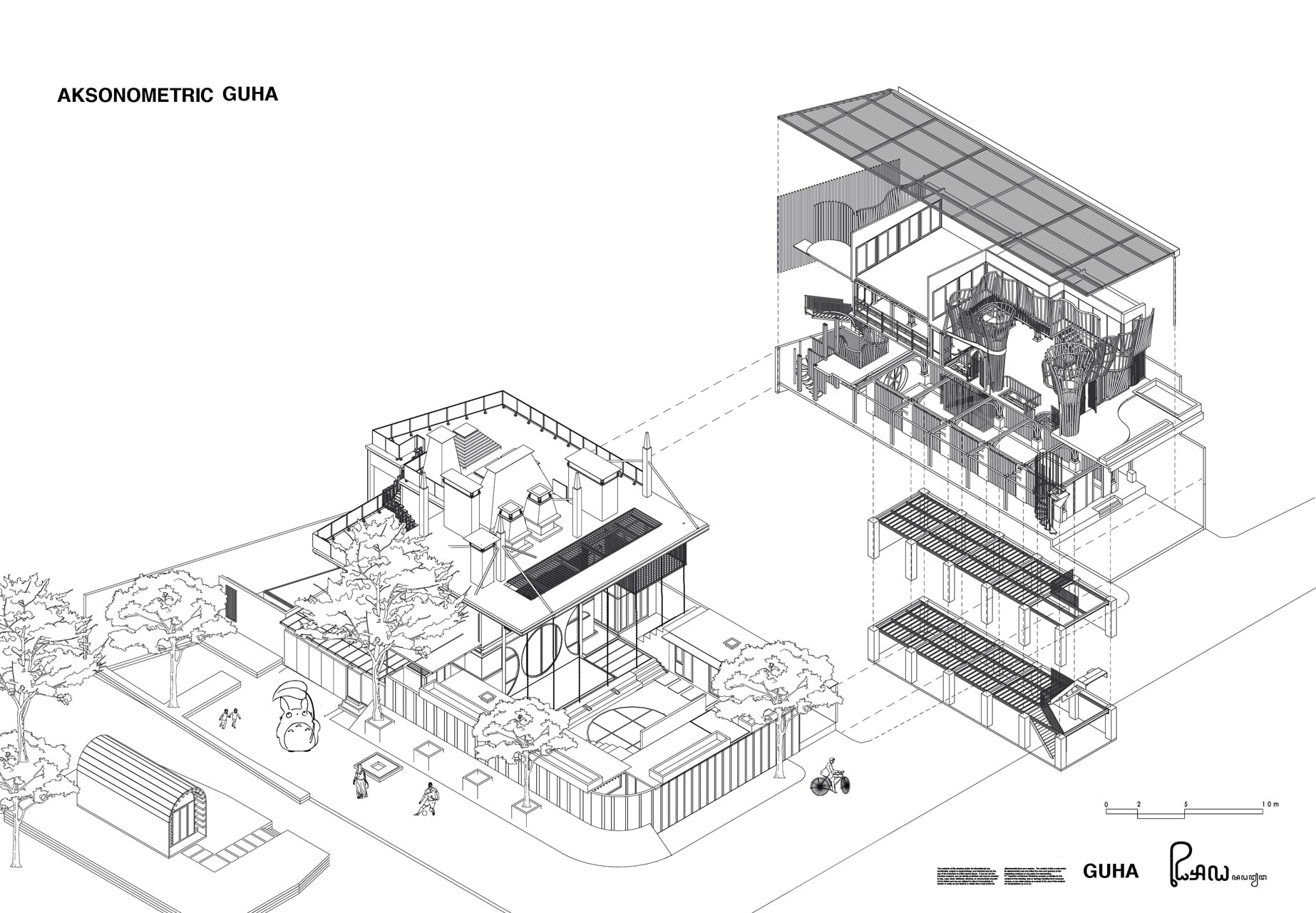

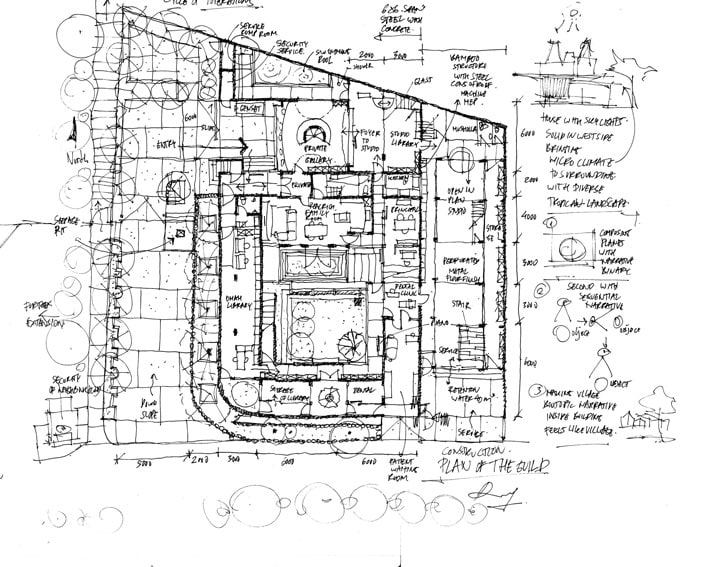

리얼리치 샤리프(리얼리치): 이 프로젝트는 기존주택 건물을 나의 가족이 살 집이자 사무실로 2016년 개조한 길드에 2020년 대나무 구조의 건물을 신축하여 구하’라는 이름으로 완성했다. 구하는 동굴을 뜻하는 산스크리트어에서 유래했으며 ‘카르티케야(Kartikeya)’라는 전쟁의 신을 의미하기도 한다. 건물은 길드 영역으로 오마(OM사1)도서관, 치과, 주택, 그리고 사무실로 쓰고 있는 ‘구하 밤부(Guha Bambu)’라는 스튜디오로 이루어져 있는데, 끊임없이 탐구하고 싶은 개인적인 소망을 실현한 프로젝트다. 2015년부터 이 건물에서 ‘문법’을 형성하기 위한 텍토닉을 실험했고 이것이 여러 단계에 걸쳐 완성됐다. 각 단계별로 콘크리트, 나무, 철, 돌, 대나무에 이르기까지 재료에 적합한 구조적 문법을 보여준다. 단계를 진행할 때마다 나는 형태와 공간, 건축적 시스템을 통합하여 문제를 해결하고 건축을 형성하는 다른 방법들이 있음을 이해하며 작업했다.

리얼리치: 다른 건축가들처럼 예술가들의 작업에 영향을 반기도 했다. 인도네시아를 대표하는 예술가로 세 명의 거장이 있다. 예술 자체를 담론으로 삼은화가 신두 수조요노(Sindu Soedjojono,1913~1986), 전문적인 기술 지식을 바탕으로 작업한 리얼리즘화가 바수키 압둘라(Basoeki Abdullah, 1915~1993), 육체와 미각을 표현하는 화가 구수마 아판디(Koesoema Affandi, 1907~1990)이다. 나는 이들의 사상이 만나는 지점이 예술과 건축의 경계를 관통한다고 믿는다. 이는 곧 수조요노가 주창한 ‘지우 케톡(Jiwo Ketok)'개념이댜 인도네시아어로 눈에 보이는 영혼을 뜻하는 이 개념은 건축에서는 거대한 것에서 작은 것으로, 적절한 디테일을 완성해가는 전체적 인 설계 프로세스를 거치며 발전된다. 이러한 디테일은 많은 실패와 실험을 포함하는 학습과정에서 얻어지는 경험의 산물이다. 내가 답을 찾지 못하고 헤맬 때 아버지는"기본으로 돌아가라”고 말했다. 이 말은 우리가 어디에 있는지, 어떻게 확고한 기반을 다져야 하는지 알려주었다. 이런 경험을 통해 얻은 해법들을 모아 구축한 것이 구조 문법 (tectonic grammar) 이다. 이를 바탕으로 나는 주거와 업무 영역이 가변성을 가지고 미래에 대응할 수 있게 개축과 증축을 고려하며 작업했다.

리얼리치: 건물은1990년대 전후에 개발된 주택단지에 위치한다. 남쪽에는 기능적으로 지어진 지중해 양식이 혼합된 집들이 즐비하며 북쪽에는 좁은 길로 접근가능한 모스크와 단층 하숙집, 가선물로 만든 커피숍, 거리 가판대, 급식소등이 있다. 남북의 주변 여건 차이로 생기는 특징 외에, 남쪽으로는 2m 정도 경사가 있고 진입로인 서쪽은 15분 이상 비가 오면 침수되는 열악한 지역이다.

박: 길드에서는 집과 설계사무실이 한 건물에 있는데 주거와 업무 기능은

어떻게 구분하고 연결했나? 외부인에게 열린 작업실 은 1층에

있는데 입구와 도서관, 야외 연못과 수영장이 혼재되어 보인다.

리얼리치: 배치는 크게 두 영역으로 나뉘는데, 업무 공간이 1층에 있기 때문에 주거는 위층에 두었다. 서쪽 주출입구로 들어서면 작은 테라스가 나온다. 사람들을 맞이하는 이 공간을 지나면 두 개의 문이 보인다. 하나는 사무실과 거실로 연결되며, 다른 하나는 도서관과 중정으로 연결된다. 서쪽 담을 따라 긴 형태로 만들어진 도서관은 연못과 중정으로 가는 실내 통로로 이어지고 1층에는 직원용 팬트리와 식당이 있다. 2층에는 가족만 사용하는 팬트리와 식당이 있고, 벽면을 가득 채운 원형 창을 통해 연못과 중정으로 바로 연결된다. 직원들의 업무 영역과 주거 영역의 동선은 현관의 테라스에서 나뉘지만, 중정을 통해 모두 이어지는 구조다.

박: 중정이 프로그램의 연결을 도모한다고 이야기했는데, 인도네시아 건축에서 자주 보이는 외부와 내부의 연결은 기후 영향이 크다고 생각한다. 더불어 내부에서 바라보는 야외 조경이 상당히 계획적이다. 어떤 의도와

고민을 배경으로 만들어졌는지 궁금하다.

리얼리치: 건물에서 200m 정도 떨어진 곳에 도로가 있는데 길의 수로 쪽에 경사가 약했다. 단지 내 다른 도로에 비해 레벨이 낮고 물이 빠져나갈 자체 수로도 없었다. 따라서 길드의 설계는 기본적으로 기후에 따른 국지성 침수 예방에 초점을 맞춰 진행되었다. 집 주변에 높이 12m의 나무 세 그루가 남쪽 건물을 에워싸고 있어 미시 기후에 어울리는 쾌적한 환경 조성에 초점을 맞춰 설계했다. 구하에서도 같은 의도가 반영되었다. 야생식물에서 선별한 잡초, 프란지파니 나무, 풀 등 관리하기 쉬운 식재로 조경을 구성했다. 최대한 단순하게 녹지를 만들어 겉치레가 아닌 진짜 ‘미시기후'를 구현하기 위해서다. 주위 온도를 낮추면서도 아름다운 환경을 만들어보겠다는 일종의 실험이었다. 시간이 흐르면서 단열 역할을 하는 덩굴과 그늘을 만드는 여러 식물을 도입하게 되었다. 점차 길드는 숲처럼 변해 작은 연못까지 갖추게 되었고, 나중에 있을 공공도서관의 점진적인 변화도 수용할 수 있도록 했다.

리얼리치: 중요한 부분을 잘 지적했다. 언급한 요소들의 형태는 케라왕(Kerawang)에 있는 바투자야(Batujaya) 사원과 보로부두르(Borobudur) 사원 같은 오래된 석재 구조에서 영감을 얻었다. 이 구조물들은 세 가지 측면에서 매력적이다. 첫째, 오래된 창의적인 기술이 빚은 일종의 건축적 표현이다. 둘째, 작품의 구조가 정체성을 찾기 위한 대담한 표현의 결과이다. 셋째, 역설적으로 이 작품들은 스스로 주변과 조화롭게 하는 다중해석적 담론을 제기하며 그 경계를 확장하는 특징을 지녔다. 이런 특성을 살려 프로젝트에 대입하는 과정에서 우리의 현실과 상황에 맞게 형태를 변형하여 적용하면서 반복적인 형태들이 포함되었다. 건물 안으로 자연광을 들이고 바람길을 만들자는 구상이었다. 원시적 형태의 디자인 요소들이 실험적이기도 하지만, 리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍을 대중과 연결해 주리라 생각했다. 단순하고 원형적인 모든 형태는 구조 문법, 물성을 다루는 것, 내가 느끼는 것을 만들고 내가 만든 것을 느끼는 것으로, 지역의 전통문화와 기후에서 기인한다.

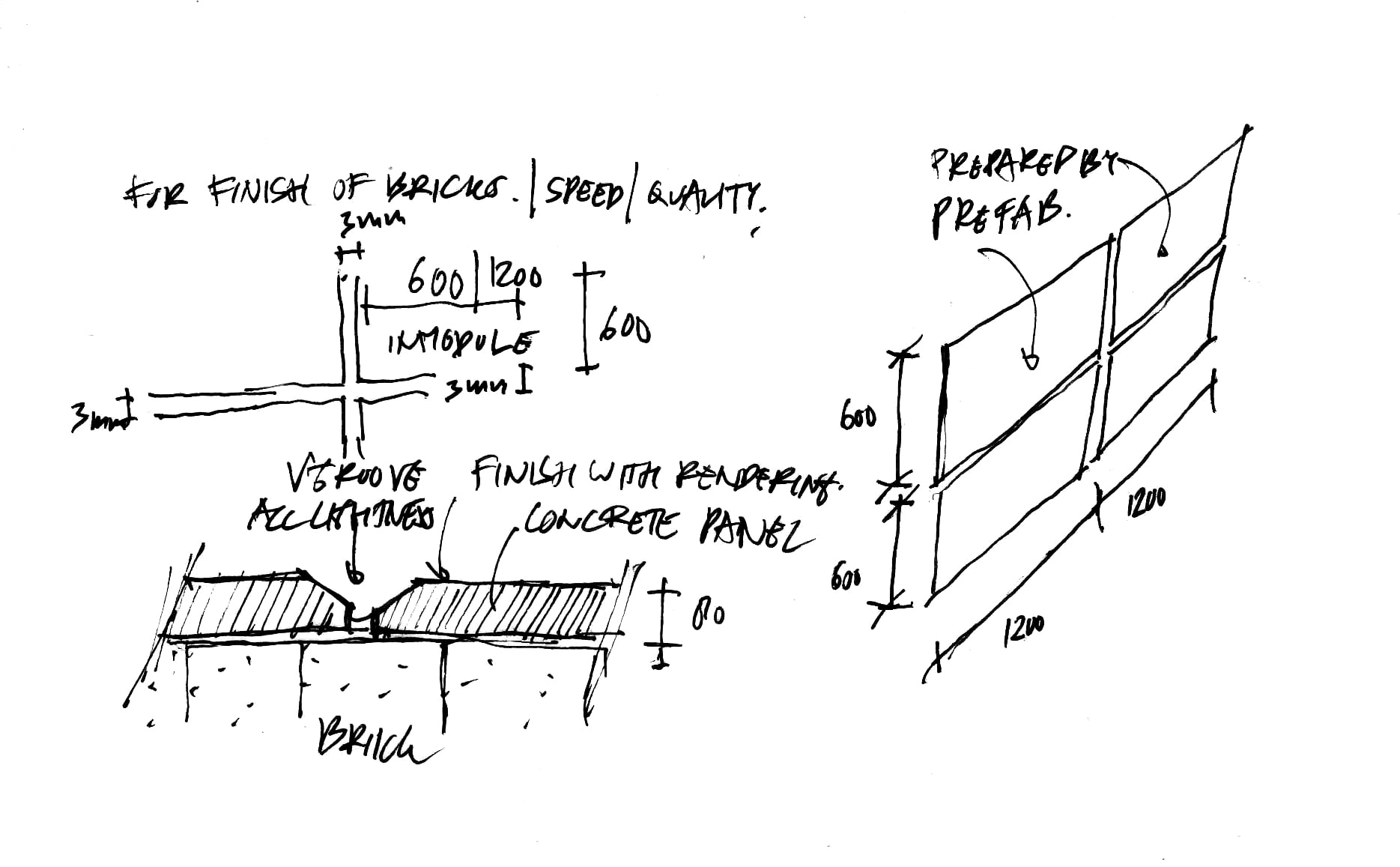

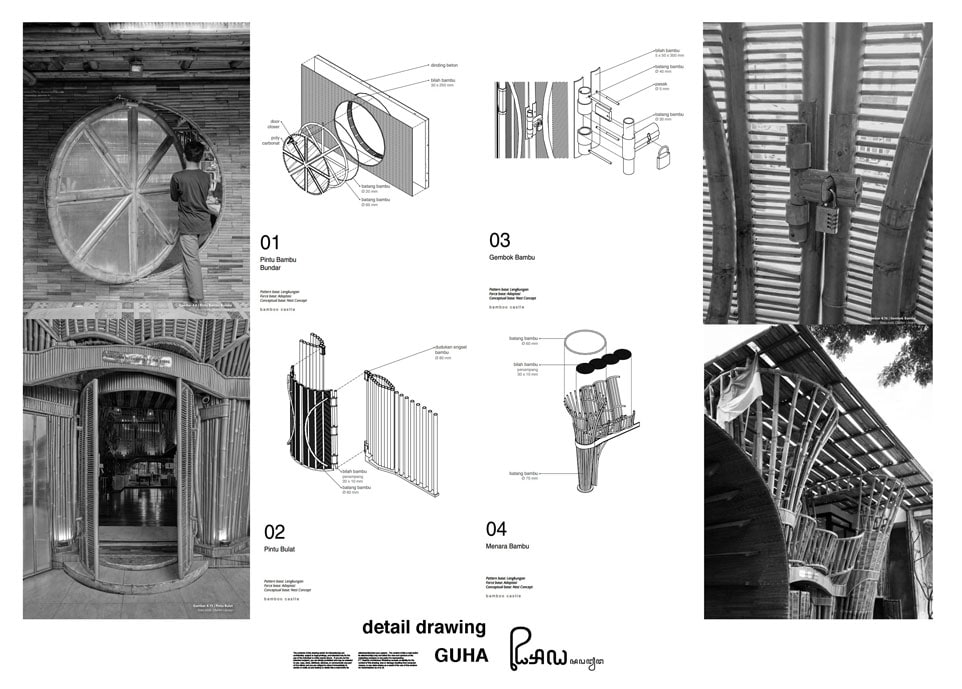

리얼리치: 효율과 미학을 고려해 디자인한 문을 크기별로 만들지 않고, 하나를 복제해 프로젝트 전체에 사용했다. 우리는 도면을 수집, 검토하고, 세부사항을 익히는 방식으로 연구를 진행한다. 프로젝트가 완료되는 시점까지 그리고 다음 단계의 프로젝트로 이어질 과정 속에서 끊임없이 디테일을 결정해가는 방식이다. 틀을 잡는 과정에서 패턴, 힘, 개념 등 세 가지 매개변수를 바탕으로 디테일을 선정하는 몇 가지 기준이 있었다. 이 작품에는 콘크리트, 돌, 나무, 벽돌, 플라스틱, 유리, 금속, 대나무 등 여덟 가지 재료가 쓰였다. 재료마다 다른 성격을 가지고 있어, 재료별로 디테일 작업 범주에 대한 추가적인 개념을 만드는 것이 작업의 목표였다. 우리는 최적의 설계로 건축의 다양성을 보여주는 동시에 기후와 문화를 지속가능한 건축으로 연결하기 위해 현지에서 구할 수 있는 재료를 사용했다.

리얼리치: 텍토그램(tectogram)은 우리의 여러 경험과 시행착오를 집약하여 정리한 시적 언어다. 앞서 말한 ‘지우 케톡’은 텍토그램의 접점으로 귀결되면서 만들어진 개념이다. 언급했던 전통 사원들을 찾아갈 때면 나는 구축된 결과물들이 초기 계획에 부합하는지 어떻게, 왜 그런 지를 거듭 자문한다. 이는 설계 방법론과 설계 구현이라는 두 단어로 집약되는데 사실 두 가지 모두를 발전시키려면 이들을 지속적으로 개발해서 변형할 수 있어야 한다. 둘 다 표준화, 계획화 등 재평가해야 할 요소들이며 실현은 텍토그램의 세계, 방법론은 메소드그램(methodgram)의 세계로 펼쳐진다.

오마도서

박: 여러 공간 중 ‘오마도서관’에 관해 묻고 싶다. 교육 목적의 다양한 프로그램이 진행되고 있는데, 이 건물에서도 중요한 내용일 것 같다. 이런 프로그램은 누구를 대상으로

어떻게 시작되었나?

리얼리치: 수라바야국립공과대학교에서 건축과 학생들의 최종 평가를 마친 뒤에 갑자기 20명 정도 학생 이 우리 사무실에서 인턴십을 하고 싶다고 지원했다. 다 받아주고 싶었지만 그러기엔 공간이 부족했다. 이런 고민을 부모님과 의논하고 비어있던 정원 한쪽에 파빌리온 짓는 것을 허락받았다. 이곳에서 학생 인턴들과 토론하고 건축적인 경험을 공유하면서 서로 많은 것을 배울 수 있었다. 학생들이 학교로 돌아간 뒤 오마도서관을 세우기로 마음먹었다. 도서관으로 사용하는 파빌리온 문을 열고 더 많은 동네 사람들이 이용하게 되었다. 나는 내가 살고 있는 이곳을 아름다운 장소로 발전시키고 싶다. 이곳을 통해 건축의 소중함을 이해하고 논쟁할 수 있는 친구가 생겼으면 한다.

리얼리치: 나는 시대의 변화를 반영하기 위해 이 현상을 예의주시하고 있다. 그리고 팬데믹 상황이 가져올 영향을 연구하고 세 가지로 예측했는데 첫째, 건축프로젝트의 진행 속도가 매우 느려질 것이고, 둘째, 분산형 스튜디오 팀과 프로덕션 팀의 통합이며, 셋째, 뉴노멀(new normal)에 도달하고 이를 평가할 때라는 점이다. 보다 건강한 환경을 조성하려면 실질적인 삶의 질을 향상시키는 프로젝트가 많아져야 한다. 고층, 고밀도 도시 생활 사이의 중간지대를 찾는 프로젝트들이다. 새로운 밀도 개념의 시대, 새로운 도시환경에서 우리 도시의 발전을 모색하는 것에 대해 건축가들이 목소리를 낼 필요가 있다고 생각한다.

리얼리치: 정체성은 인도네시아 건축가들에게도 여전한 문제다. 많은 젊은 건축가들이 장식을 통해 개성을 만들려고 하는데, 낮은 차원의 얕은 생각에서 깊은 사색적 고민에 이르는 과정이라고 생각한다. 건축비평가인 유숩 빌야르타 만군위자야(Yusuf Bilyarta Mangunwijaya, 1929~1999)는 1990년대 ‘인도네시아의 젊은 건축가포럼(AMI)’에 대해 총체적인 개념 없이 형태만 가지고 유희성에 탐닉할 뿐 사회주택의 필요성 등 사회적 문제는 다루지 않는다고 비판하기도 했다. 현재 인도네시아는 개발이 급격히 확산되고 있다. 공공주택과 주택소유에 대한 요구가 늘어나면서 건설, 건축산업 또한 꾸준히 성장하는 추세다. 이러한 수요에 맞춰 2017년에는 새 건축법이 제정되었고, 2018년 기준 등록된 공인건축가는 1만 8,000여 명으로 전해보다 7,000명이나 늘었다. 새롭게 입문한 많은 신생 건축가들이 지역사회 안에서 건전한 산업생태계를 구축하도록 이끄는 것이 숙제이지 않을까?

리얼리치: 인도네시아 대학 학부에서는 건축의 기술적인 스킬을 중점적으로 교육한다. 하지만 해외 건축사무소에서는 비판적 사고를 통해 건축을 생산하는 방법과 이론을 제안하는 창의력을 요구했다. 해외 유학과 실무 경험은 이런 비판적 사고와 창의성을 토대로 우리의 전통과 역사를 새롭게 바라보는 계기가 되었다. 우리는 침략 이전 시대, 식민지 시대를 거쳐 식민지 이후의 시대를 살고 있다. 인도네시아는 300여 개의 부족이 쌓아온 풍요로운 문화와 현대적인 삶이 조화를 이룬 다양성을 가진 나라다. 먼 미래에는 산업 자체의 논리에 따라, 인도네시아 건축에서 새로운 기술과 전통적인 장인정신을 연결하는 것이 그다지 중요하지 않을 수도 있다. 그러나 리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍은 문화를 형성하는 것은 ‘인간’이라고 생각한다. 문화와 건축가라는 사람 사이에서 독특한 무언가가 만들어질 것이다. 나는 건축기술과 장인정신을 통합할 때 어떻게 해야 비판적인 동시에 창의적일 수 있는지 오래 고민해왔다. 그래서 우리의 역할을 ‘영감을 주는 재료에 대한 실험을 전통으로 연결하는 통로(rahayu meaning being bridge)’로서 다시 정의하게 되었다. 현재 인도네시아 건축 흐름에서 디자인 문제를 정의하거나 출발점을 찾을 때 맥락을 이해하는 방법이 가장 핵심적인 문제일 것이다. 과거의 사고방식에서 벗어나, 보다 자유로운 생각을 통해 전통을 잃지 않고 혁신하는 것이 우리의 과제다. 이를 해결하는 기본은 기후와 문화가 될 것이다. 다원적인 접근이 이뤄질 미래를 바라보며, 기술과 건축을 어떻게 통합할지 어떤 접근법을 사용할지 지금도 고민하고 있다.

Realrich Architecture Workshop_ Realrich Sjarief

EXPLORING THE CONNECTIONS BETWEEN TRADITION AND TECHNOLOGY

After establishing his Realrich

Architecture Workshop in 2011, Realrich Sjarief is currently involved in

architectural activities that emphasizes locality and handcraft. He graduated

from the Institute Technology of Bandung in Indonesia, did his masters at the

University of New South Wales in Australia, and built his career at Foster +

Partners in the UK and DP Architects in Singapore. He was also awarded the

Jakarta Award from the Indonesian Institute of Architects in 2017. As an artist

and educator, he is working to contribute to society via architecture through

his OMAH Library.

Realrich Sjarief (Realrich): Guild is the renovation project I oversaw, rehasping my personal residence to convert the space into a residence and office. This was then renovated again in 2020 with a new bamboo-structure building added to its eastern side under the name Guha. Guha originates from a Sanskrit word that means 'cave', but it also alludes to the war-god Kartikeya. Guild consists of the OMAH Library, the dental clinic run by my wife, and the residence, while 'Guha' consists of a studio known as Guha Bambu that I use as the studio office. This final element ofthe project is a manifestation of my personal desire to endlessly explore form and ideas. In this building, I have experimented with tectonics since 2015 to create its 'grammar', and this was completed over the course of multiple phases. In each phase - from concrete, wood, metal, masonry, and bamboo - there is a structural grammar that matches with each respective material. When I was performing these steps, I tried to resolve any problems by integrating form, space, and the architectural system while also ensuring consideration of other possibilities in terms of architectural formation.

Realrich: Like other architects, I was inspired by artwork. There are three figures from twentieth-century Indonesian art here that provided the greatest influence: the artist Sindu Sudjojono (1913 -1986), who approached art as a discourse; the realist painter Basuki Abdullah (1915 -1993), who set his technical knowledge as a background to his work, and the artist Koesoema Affandi (1907 -1990), who focused on the gestures of the body and expressions of beauty. I believe that the point at which the ideologies of these three masters meet cuts across any perceived boundaries between art and architecture. This is what Sudjojono meant by his concept 'Jiwo Ketok'. This concept, which refers to the idea of a visible soul, proceeds from something massive to something minute in architecture, and develops through the perfecting of working details throughout the entire design process. These details are the result of lengthy experience; one learns by encountering numerous failures and experiments. My father once told me to 'go back to the basics' when I was lost and unable to find a solution to a design problem. What he said helped me to realize where one is, and how one must build a stable foothold. By gathering, the means of overcoming such h experiences, I was able to establish my tectonic grammar. With this as background, I worked on the residential and office building while considering its variability and flexibility for future renovations and expansions.

Realrich: The building is in a residential district that was developed in the 1990s. Towards the south, rows of functionally- designed houses with the odd glimmer of Mediterranean design can be found, while towards the north, there is a mosque, single-floor boarding houses, cafes made of temporary structures, street kiosks, and food catering businesses that can be accessed via a narrow road. Other than the differences caused by the gap in the conditions between the north and the south, there is also an inclined slope of about 2m towards the south. The western area, where an access road is located, is also prone to flooding when it rains for more than 15 minutes.

Realrich: The positioning can be largely divided into two areas. Since the workspace is on the lobby floor, the residential space was placed upstairs. There is a small terrace at the western main entrance. Across this space for receiving guests, two doors can be found. One door leads to the office and the living room, while the other leads to the library and the central courtyard. The library, of an elongated shape alongside the western wall, is connected to the interior corridor that connects the pond to the courtyard, as well as to the pantry and dining hall for the staff on the first floor. The pantry and dining hall for the family, however, is on the second floor, while a circular window that covers the entire wall is focused on the pond and the courtyard. The circulations of the working area and the residential area are kept separated thanks to the terrace at the main entrance, but they are all also linked through the courtyard.

Realrich: There is a street at about 200m away from the building, and the descent to the water channel is too small. Moreover, its level is lower than the other streets in the area, and water cannot flow out of it. Because of this, the design for the Guild was conducted according to a focus upon the prevention of local flooding due to its wet climate. Also. in response to the three 12m-high trees surrounding the southern building, I designed the building with the aim of creating an environment that suits its given micro-climate. The same intention was replicated in Guha. Selected wild plants, frangipani trees, and grass -plants that are easy to manage -were chosen to organize the landscape. This was not merely to create a green space for aesthetic appreciation, but to realize an actual 'micro-climate'. It was a kind of an experiment to create a beautiful environment while trying to reduce the surrounding temperature. As time passed, various plants such as vines that produce shade and block the heat were also introduced. Gradually, the Guild turned into a forest, a pond was introduced, and its public library was designed to cater to further gradual modifications.

Realrich: This is an important question. The forms of these elements that you mention were inspired by ancient masonry structures such as the Batujaya temple in Kerawang and the Borobudur temple. These structures are mesmerizing for three reasons: first, the architectural expression in the ancient creative technique; second, the bold expression that results from the structure's pursuit for its unique identity; third, these works propose a multi-directional discourse that paradoxically creates harmony between themselves and their surroundings while expanding their boundaries. Such properties were reformed and reapplied to repetitive forms that fit our given situation during the project design stage. Natural light was drawn into the building, and wind paths were introduced. While ancient design elements can be experimental, I assumed that it would nonetheless help to connect Realrich Architecture with its wider public. All simple and circular forms -a tectonic grammar, as adapted material properties, and as things that I feel and make and make and feel in reverse -are derived from the region's traditional culture and climate.

Realrich: We didn't create doors of different sizes designed for efficiency and aesthetics, choosing instead to insist upon the same design throughout the entire project. We conduct our research by first observing and reviewing the floorplan and familiarizing ourselves with its details. Through this method, we make decisions continuously regarding these details during and after the project itself. When deciding on the frame, there were some criteria given in terms of choosing the details under the three parameters of pattern, force, and concept. In this work, eight materials consisting of concrete, masonry, wood, bricks, plastic, glass, metal, and bamboo were used. As each material possesses its own unique properties, the aim of the project was to create a new concept regarding the detail work category for each material. We decided to use local materials to reveal the diversity of architecture via optimized design while connecting the local climate and culture with sustainable architecture.

Park: Six long years have passed since you

began studying the various contents of this site and finally completing the

project. I assume that there are various attempts and thoughts that you've

showcased in other projects that got mixed in somewhere -if there is a concise

summary of what you've conceptualized or contemplated thus far, could you

please shed light on it?

Realrich: 'Tectogram' is a poetic language that we derived by compiling all our experiences of architectural success and failure. Jiwo Ketok, which I mentioned earlier, is a concept that we developed from the tectogram. When I visit the traditional temples to which I referred earlier, I repeatedly ask myself how and why the resulting construction fulfills its initial design ambitions. This could also be summarized in two expressions: 'design methodology' and 'design implementation'. For to evolve, the two must undergo transformations. via continuous development. Both are elements that need to be standardized, planned, and reevaluated. Implementation expands into the world of tectograms, and methodology leads one into the world of methodgrams.

Realrich: After finishing the final evaluation at the architecture department of lnstitut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, about 20 students approached me and applied for internships at our office. I wanted to take them all, but there was not enough space. I brought up this concern with my parents, and we decided to build a pavilion at one unused corner in the garden. Here, we could discuss and share architectural experiences and knowledge with the interns. After the students returned to the institute, I decided to build the OMAH Library. As I moved the pavilion to the adjacent site and built a library within the building, more locals came to use the facility. I want to develop my neighborhood and nurture it into a beautiful place. I want to make friends with whom I can debate and share a common understanding in the importance of architecture.

Realrich: I'm keeping an eye on the phenomenon with the long-term changes to our era in mind. I researched the impact that the pandemic situation might bring about and have come up with three possibilities: first, that architectural projects would be greatly slowed down; second, that there might be integration between decentralized studio teams and production teams; third, a new normal would be reached and there would be a need to evaluate its culture and conditions. To create a healthier environment, there needs to be more projects that improve actual quality of life―and by that, I mean the projects that seek a middle ground between the high-rise and high-density urban life of our cities. Regarding the search for urban development within an era of a new density concept and a new urban environment, there is a need for architects to step up and make their voices heard.

Realrich: Identity is also an issue that remains pertinent to Indonesian architects. Many young architects try to define their unique aspect through ornamentation, and I think this represents a process that leads from shallower thinking to deep and profound contemplation. An architecture critic YusufBilyarta Mangunwijaya (1929 -1999) once commented of the Young Indonesian Architects Forum in the 1990s that it lacked a holistic concept and was merely interested in playing with forms without dealing with the needs of social residences or social issues. Presently, Indonesia is rapidly growing in terms of its development. There is a high demand for public and private residences, and with this there is a sustained growth in the construction and architectural industries. A new architectural law was implemented in 2017 to respond to this rising demand, and the number of registered architects has increased by 7,000 from 18,000 in 2018. The task is then to guide these new architects to build a healthier industrial ecosystem in their regional societies.

Realrich: The undergraduate programs in Indonesian universities mainly focus on the technical skills behind architectural design. At the architectural offices overseas, however, they ask for critical thinking and creativity to propose new methods and innovative theories for producing architecture. This training, in critical thinking and creativity, during my overseas education and work experience led me to view my home traditions and history in a new way. The postcolonial period in which we live now was preceded by the colonial period and the pre-colonial period. Indonesia is a country with a rich cultural diversity of approximately 300 different tribes that now exist in harmony with the more modern aspects of life. Perhaps in the industrial standards established in a distant future, it might not be as important to connect new technologies with traditional artisanship. However, here at Realrich Architecture, we believe that it is 'humans' who form culture. There will be something unique created between culture and the architect as a human being. I have always contemplated how to be both critical and creative when integrating architectural techniques with artisanship. As such, we came to redefine our roles as a 'rahayu' (bridges) that connect experiments with inspirational materials to tradition. Contemporary architectural trends in Indonesia are characterized by a core problem in the way one understands the context when defining the design issue or locating a starting point. Our task is to go beyond the old critical methods and to revolutionize with freer means of thinking without losing touch with our tradition. The fundamental solution for this would be a focus on climate and culture. As we now face a future of pluralistic approaches, we constantly think about how to integrate technique and architecture, and what approaches we should employ.

전통과 기술의 접점을 탐구하다

리얼리치 샤리프는 2011년 리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍을 설립하여 지역성과

수공예를 강조하는 건축 활동을 이어가고 있다, 인도네시아 반둥 공과대학교를 졸업하고, 호주 뉴사우스웨일스 대학교에서 건축학석사 학위를 받았다, 이후 영국

포스터 앤드 파트너스와 싱가포르 디피아키텍츠에서 실무경력을 쌓았다, 2017년인도네시아 건축가협회 자카르타

어워드를 수상했으며, 직접 설립한 오마도서관을 통해 작가와 교육자로서 건축의 사회적 가치 실현에도 힘쓰고

있다.

리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍은 인도네시아 자카르타에서 활동하는 젊은 건축가그룹이다.

재료에 대한 실험을 통해 현대건축과 전통기술의 접점을 모색하며 다양한 활동을 펼치고 있다. 리얼리치

아키텍처 워크숍의 대표이자 3세대 건축가인 리얼리치 샤리프와 인도네시아의 건축상황과 동시대 건축가의

고민에 대해 서면으로 이야기를 나눴다.

박창현(박): 리얼리치

아키텍처 워크숍의 대표작인 ‘구하(Guba)’는 두 번의

리노베이션으로 완성된 프로젝트로, 시간이 지날수록 다양하게 바뀌어서 흥미롭다. 주택가 건물을 개조한 첫 번째 작업을 ‘길드(Guild)', 중개축한 두 번째 작업을 ‘구하’라고 이름 붙였다.

리얼리치 샤리프(리얼리치): 이 프로젝트는 기존주택 건물을 나의 가족이 살 집이자 사무실로 2016년 개조한 길드에 2020년 대나무 구조의 건물을 신축하여 구하’라는 이름으로 완성했다. 구하는 동굴을 뜻하는 산스크리트어에서 유래했으며 ‘카르티케야(Kartikeya)’라는 전쟁의 신을 의미하기도 한다. 건물은 길드 영역으로 오마(OM사1)도서관, 치과, 주택, 그리고 사무실로 쓰고 있는 ‘구하 밤부(Guha Bambu)’라는 스튜디오로 이루어져 있는데, 끊임없이 탐구하고 싶은 개인적인 소망을 실현한 프로젝트다. 2015년부터 이 건물에서 ‘문법’을 형성하기 위한 텍토닉을 실험했고 이것이 여러 단계에 걸쳐 완성됐다. 각 단계별로 콘크리트, 나무, 철, 돌, 대나무에 이르기까지 재료에 적합한 구조적 문법을 보여준다. 단계를 진행할 때마다 나는 형태와 공간, 건축적 시스템을 통합하여 문제를 해결하고 건축을 형성하는 다른 방법들이 있음을 이해하며 작업했다.

박: 설계의 시작 단계나 발전 과정에는 항상 어려움이 있다. 그런 상황에서 건축 외적으로 영감이나 영향을 받은 것은 무엇이었나?

리얼리치: 다른 건축가들처럼 예술가들의 작업에 영향을 반기도 했다. 인도네시아를 대표하는 예술가로 세 명의 거장이 있다. 예술 자체를 담론으로 삼은화가 신두 수조요노(Sindu Soedjojono,1913~1986), 전문적인 기술 지식을 바탕으로 작업한 리얼리즘화가 바수키 압둘라(Basoeki Abdullah, 1915~1993), 육체와 미각을 표현하는 화가 구수마 아판디(Koesoema Affandi, 1907~1990)이다. 나는 이들의 사상이 만나는 지점이 예술과 건축의 경계를 관통한다고 믿는다. 이는 곧 수조요노가 주창한 ‘지우 케톡(Jiwo Ketok)'개념이댜 인도네시아어로 눈에 보이는 영혼을 뜻하는 이 개념은 건축에서는 거대한 것에서 작은 것으로, 적절한 디테일을 완성해가는 전체적 인 설계 프로세스를 거치며 발전된다. 이러한 디테일은 많은 실패와 실험을 포함하는 학습과정에서 얻어지는 경험의 산물이다. 내가 답을 찾지 못하고 헤맬 때 아버지는"기본으로 돌아가라”고 말했다. 이 말은 우리가 어디에 있는지, 어떻게 확고한 기반을 다져야 하는지 알려주었다. 이런 경험을 통해 얻은 해법들을 모아 구축한 것이 구조 문법 (tectonic grammar) 이다. 이를 바탕으로 나는 주거와 업무 영역이 가변성을 가지고 미래에 대응할 수 있게 개축과 증축을 고려하며 작업했다.

박: 지금 말한 내용이 길드와 구하에 그대로 들어있다고 생각한다. 프로젝트는 자카르타의 한적한 주거지에 지어졌는데 주변은 어떤 특징을 가진 동네인가?

리얼리치: 건물은1990년대 전후에 개발된 주택단지에 위치한다. 남쪽에는 기능적으로 지어진 지중해 양식이 혼합된 집들이 즐비하며 북쪽에는 좁은 길로 접근가능한 모스크와 단층 하숙집, 가선물로 만든 커피숍, 거리 가판대, 급식소등이 있다. 남북의 주변 여건 차이로 생기는 특징 외에, 남쪽으로는 2m 정도 경사가 있고 진입로인 서쪽은 15분 이상 비가 오면 침수되는 열악한 지역이다.

박: 길드에서는 집과 설계사무실이 한 건물에 있는데 주거와 업무 기능은

어떻게 구분하고 연결했나? 외부인에게 열린 작업실 은 1층에

있는데 입구와 도서관, 야외 연못과 수영장이 혼재되어 보인다.

리얼리치: 배치는 크게 두 영역으로 나뉘는데, 업무 공간이 1층에 있기 때문에 주거는 위층에 두었다. 서쪽 주출입구로 들어서면 작은 테라스가 나온다. 사람들을 맞이하는 이 공간을 지나면 두 개의 문이 보인다. 하나는 사무실과 거실로 연결되며, 다른 하나는 도서관과 중정으로 연결된다. 서쪽 담을 따라 긴 형태로 만들어진 도서관은 연못과 중정으로 가는 실내 통로로 이어지고 1층에는 직원용 팬트리와 식당이 있다. 2층에는 가족만 사용하는 팬트리와 식당이 있고, 벽면을 가득 채운 원형 창을 통해 연못과 중정으로 바로 연결된다. 직원들의 업무 영역과 주거 영역의 동선은 현관의 테라스에서 나뉘지만, 중정을 통해 모두 이어지는 구조다.

박: 중정이 프로그램의 연결을 도모한다고 이야기했는데, 인도네시아 건축에서 자주 보이는 외부와 내부의 연결은 기후 영향이 크다고 생각한다. 더불어 내부에서 바라보는 야외 조경이 상당히 계획적이다. 어떤 의도와

고민을 배경으로 만들어졌는지 궁금하다.

리얼리치: 건물에서 200m 정도 떨어진 곳에 도로가 있는데 길의 수로 쪽에 경사가 약했다. 단지 내 다른 도로에 비해 레벨이 낮고 물이 빠져나갈 자체 수로도 없었다. 따라서 길드의 설계는 기본적으로 기후에 따른 국지성 침수 예방에 초점을 맞춰 진행되었다. 집 주변에 높이 12m의 나무 세 그루가 남쪽 건물을 에워싸고 있어 미시 기후에 어울리는 쾌적한 환경 조성에 초점을 맞춰 설계했다. 구하에서도 같은 의도가 반영되었다. 야생식물에서 선별한 잡초, 프란지파니 나무, 풀 등 관리하기 쉬운 식재로 조경을 구성했다. 최대한 단순하게 녹지를 만들어 겉치레가 아닌 진짜 ‘미시기후'를 구현하기 위해서다. 주위 온도를 낮추면서도 아름다운 환경을 만들어보겠다는 일종의 실험이었다. 시간이 흐르면서 단열 역할을 하는 덩굴과 그늘을 만드는 여러 식물을 도입하게 되었다. 점차 길드는 숲처럼 변해 작은 연못까지 갖추게 되었고, 나중에 있을 공공도서관의 점진적인 변화도 수용할 수 있도록 했다.

박: 중정이나 입면의 창, 천창 등의 형태는 인도네시아 특유의 디자인으로 아주 인상적이다. 구조적으로도 많은 스터디를 거친 결과로 보이는데 어떻게 도출된 형태인가?

리얼리치: 중요한 부분을 잘 지적했다. 언급한 요소들의 형태는 케라왕(Kerawang)에 있는 바투자야(Batujaya) 사원과 보로부두르(Borobudur) 사원 같은 오래된 석재 구조에서 영감을 얻었다. 이 구조물들은 세 가지 측면에서 매력적이다. 첫째, 오래된 창의적인 기술이 빚은 일종의 건축적 표현이다. 둘째, 작품의 구조가 정체성을 찾기 위한 대담한 표현의 결과이다. 셋째, 역설적으로 이 작품들은 스스로 주변과 조화롭게 하는 다중해석적 담론을 제기하며 그 경계를 확장하는 특징을 지녔다. 이런 특성을 살려 프로젝트에 대입하는 과정에서 우리의 현실과 상황에 맞게 형태를 변형하여 적용하면서 반복적인 형태들이 포함되었다. 건물 안으로 자연광을 들이고 바람길을 만들자는 구상이었다. 원시적 형태의 디자인 요소들이 실험적이기도 하지만, 리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍을 대중과 연결해 주리라 생각했다. 단순하고 원형적인 모든 형태는 구조 문법, 물성을 다루는 것, 내가 느끼는 것을 만들고 내가 만든 것을 느끼는 것으로, 지역의 전통문화와 기후에서 기인한다.

박: 천창뿐만 아니라 건물 곳곳에 실험적인 요소들이 많이 보인다. 각요소들의 역할은 무엇이며, 어떤 의도로 주거와 업무 공간에 적용되었나?

리얼리치: 효율과 미학을 고려해 디자인한 문을 크기별로 만들지 않고, 하나를 복제해 프로젝트 전체에 사용했다. 우리는 도면을 수집, 검토하고, 세부사항을 익히는 방식으로 연구를 진행한다. 프로젝트가 완료되는 시점까지 그리고 다음 단계의 프로젝트로 이어질 과정 속에서 끊임없이 디테일을 결정해가는 방식이다. 틀을 잡는 과정에서 패턴, 힘, 개념 등 세 가지 매개변수를 바탕으로 디테일을 선정하는 몇 가지 기준이 있었다. 이 작품에는 콘크리트, 돌, 나무, 벽돌, 플라스틱, 유리, 금속, 대나무 등 여덟 가지 재료가 쓰였다. 재료마다 다른 성격을 가지고 있어, 재료별로 디테일 작업 범주에 대한 추가적인 개념을 만드는 것이 작업의 목표였다. 우리는 최적의 설계로 건축의 다양성을 보여주는 동시에 기후와 문화를 지속가능한 건축으로 연결하기 위해 현지에서 구할 수 있는 재료를 사용했다.

박: 다양한 내용을 스터디하며 진행해서인지 전체 프로젝트를 완성하는 데 6년이라는 긴 시간이 걸렸다. 그간 작업한 다른 프로젝트들에서 선보인 다양한 시도와 생각들이 겹쳐 있을 것이라 생각되는데, 이를 통해 정리된 개념이나 내용이 있다면 소개해 달라.

리얼리치: 텍토그램(tectogram)은 우리의 여러 경험과 시행착오를 집약하여 정리한 시적 언어다. 앞서 말한 ‘지우 케톡’은 텍토그램의 접점으로 귀결되면서 만들어진 개념이다. 언급했던 전통 사원들을 찾아갈 때면 나는 구축된 결과물들이 초기 계획에 부합하는지 어떻게, 왜 그런 지를 거듭 자문한다. 이는 설계 방법론과 설계 구현이라는 두 단어로 집약되는데 사실 두 가지 모두를 발전시키려면 이들을 지속적으로 개발해서 변형할 수 있어야 한다. 둘 다 표준화, 계획화 등 재평가해야 할 요소들이며 실현은 텍토그램의 세계, 방법론은 메소드그램(methodgram)의 세계로 펼쳐진다.

오마도서

박: 여러 공간 중 ‘오마도서관’에 관해 묻고 싶다. 교육 목적의 다양한 프로그램이 진행되고 있는데, 이 건물에서도 중요한 내용일 것 같다. 이런 프로그램은 누구를 대상으로

어떻게 시작되었나?

리얼리치: 수라바야국립공과대학교에서 건축과 학생들의 최종 평가를 마친 뒤에 갑자기 20명 정도 학생 이 우리 사무실에서 인턴십을 하고 싶다고 지원했다. 다 받아주고 싶었지만 그러기엔 공간이 부족했다. 이런 고민을 부모님과 의논하고 비어있던 정원 한쪽에 파빌리온 짓는 것을 허락받았다. 이곳에서 학생 인턴들과 토론하고 건축적인 경험을 공유하면서 서로 많은 것을 배울 수 있었다. 학생들이 학교로 돌아간 뒤 오마도서관을 세우기로 마음먹었다. 도서관으로 사용하는 파빌리온 문을 열고 더 많은 동네 사람들이 이용하게 되었다. 나는 내가 살고 있는 이곳을 아름다운 장소로 발전시키고 싶다. 이곳을 통해 건축의 소중함을 이해하고 논쟁할 수 있는 친구가 생겼으면 한다.

박: 펜데믹 상황은 세계인의 삶을 바꾸고 있다. 생활방식이나 인간관계도 변화하고 있는데, 특히 코로나바이러스감염증-19(코로나19)에 의한 감염률과 사망률이 높은 인도네시아에서는 어떤 변화가 일어나고 있나? 건축계에서는 어떻게 대응하고 있나?

리얼리치: 나는 시대의 변화를 반영하기 위해 이 현상을 예의주시하고 있다. 그리고 팬데믹 상황이 가져올 영향을 연구하고 세 가지로 예측했는데 첫째, 건축프로젝트의 진행 속도가 매우 느려질 것이고, 둘째, 분산형 스튜디오 팀과 프로덕션 팀의 통합이며, 셋째, 뉴노멀(new normal)에 도달하고 이를 평가할 때라는 점이다. 보다 건강한 환경을 조성하려면 실질적인 삶의 질을 향상시키는 프로젝트가 많아져야 한다. 고층, 고밀도 도시 생활 사이의 중간지대를 찾는 프로젝트들이다. 새로운 밀도 개념의 시대, 새로운 도시환경에서 우리 도시의 발전을 모색하는 것에 대해 건축가들이 목소리를 낼 필요가 있다고 생각한다.

박: 한국의 현대건축은 1920~1930년대에 태어난 1세대 건축가를 시작으로 1940~1950년대에 태어난 2세대 건축가를 거쳐, 지금은 1970~1980년대에 출생한 3세대 건축가의 활동으로 이어지고 있다. 각 세대마다 정체성에 대한 논의는 역사적 흐름 위에 있었다. 지금은 점차 역사성이라는 인식의 무게에서 살짝 벗어나, 다양한 접근으로 건축술 자체에 관심을 가지며 보다 사물적 관점에 건축을 바라보는 경향으로 바뀌고 있다.

리얼리치: 정체성은 인도네시아 건축가들에게도 여전한 문제다. 많은 젊은 건축가들이 장식을 통해 개성을 만들려고 하는데, 낮은 차원의 얕은 생각에서 깊은 사색적 고민에 이르는 과정이라고 생각한다. 건축비평가인 유숩 빌야르타 만군위자야(Yusuf Bilyarta Mangunwijaya, 1929~1999)는 1990년대 ‘인도네시아의 젊은 건축가포럼(AMI)’에 대해 총체적인 개념 없이 형태만 가지고 유희성에 탐닉할 뿐 사회주택의 필요성 등 사회적 문제는 다루지 않는다고 비판하기도 했다. 현재 인도네시아는 개발이 급격히 확산되고 있다. 공공주택과 주택소유에 대한 요구가 늘어나면서 건설, 건축산업 또한 꾸준히 성장하는 추세다. 이러한 수요에 맞춰 2017년에는 새 건축법이 제정되었고, 2018년 기준 등록된 공인건축가는 1만 8,000여 명으로 전해보다 7,000명이나 늘었다. 새롭게 입문한 많은 신생 건축가들이 지역사회 안에서 건전한 산업생태계를 구축하도록 이끄는 것이 숙제이지 않을까?

박: 세계 건축의 흐름은 여전히 유럽이나 미국중심으로 흐르고 있지만 문화의 변화는 아시아로 이동하는 추세다. 아시아가 쌓아온 역사와 문화적 토대가 그 바탕이라고 생각한다. 이런 상황에서 인도네시아 건축가로서 어떠한 문제의식을 느끼는가? 호주, 영국, 싱가포르에서의 경험은 개인의 작업에 어떤 영향을 미쳤나?

리얼리치: 인도네시아 대학 학부에서는 건축의 기술적인 스킬을 중점적으로 교육한다. 하지만 해외 건축사무소에서는 비판적 사고를 통해 건축을 생산하는 방법과 이론을 제안하는 창의력을 요구했다. 해외 유학과 실무 경험은 이런 비판적 사고와 창의성을 토대로 우리의 전통과 역사를 새롭게 바라보는 계기가 되었다. 우리는 침략 이전 시대, 식민지 시대를 거쳐 식민지 이후의 시대를 살고 있다. 인도네시아는 300여 개의 부족이 쌓아온 풍요로운 문화와 현대적인 삶이 조화를 이룬 다양성을 가진 나라다. 먼 미래에는 산업 자체의 논리에 따라, 인도네시아 건축에서 새로운 기술과 전통적인 장인정신을 연결하는 것이 그다지 중요하지 않을 수도 있다. 그러나 리얼리치 아키텍처 워크숍은 문화를 형성하는 것은 ‘인간’이라고 생각한다. 문화와 건축가라는 사람 사이에서 독특한 무언가가 만들어질 것이다. 나는 건축기술과 장인정신을 통합할 때 어떻게 해야 비판적인 동시에 창의적일 수 있는지 오래 고민해왔다. 그래서 우리의 역할을 ‘영감을 주는 재료에 대한 실험을 전통으로 연결하는 통로(rahayu meaning being bridge)’로서 다시 정의하게 되었다. 현재 인도네시아 건축 흐름에서 디자인 문제를 정의하거나 출발점을 찾을 때 맥락을 이해하는 방법이 가장 핵심적인 문제일 것이다. 과거의 사고방식에서 벗어나, 보다 자유로운 생각을 통해 전통을 잃지 않고 혁신하는 것이 우리의 과제다. 이를 해결하는 기본은 기후와 문화가 될 것이다. 다원적인 접근이 이뤄질 미래를 바라보며, 기술과 건축을 어떻게 통합할지 어떤 접근법을 사용할지 지금도 고민하고 있다.

Realrich Architecture Workshop_ Realrich Sjarief

EXPLORING THE CONNECTIONS BETWEEN TRADITION AND TECHNOLOGY

After establishing his Realrich

Architecture Workshop in 2011, Realrich Sjarief is currently involved in

architectural activities that emphasizes locality and handcraft. He graduated

from the Institute Technology of Bandung in Indonesia, did his masters at the

University of New South Wales in Australia, and built his career at Foster +

Partners in the UK and DP Architects in Singapore. He was also awarded the

Jakarta Award from the Indonesian Institute of Architects in 2017. As an artist

and educator, he is working to contribute to society via architecture through

his OMAH Library.

Realrich Architecture Workshop (hereinafter

Realrich Architecture) comprises a group of young architects based in Jakarta,

Indonesia. Through a range of experiments with materials, the team explores the

perceived connections between contemporary architecture and traditional

technologies, following these investigations up with various activities. I was

given the chance to interview.

(Via email) Realrich Sjarief- a

third-generation architect and the principal at Realrich Architecture - about

the nature of the architectural scene in Indonesia and his thoughts on working as

a contemporary architect.

Park Changhyun (Park): The primary highlight of Realrich Architecture, 'Guha', which is a project that underwent two renovations, is fascinating in that it has evolved over time so strikingly in terms of its appearance. The residential building was named as 'Guild' during its first renovation, but it was then renamed 'Guha' following the second renovation.

Realrich Sjarief (Realrich): Guild is the renovation project I oversaw, rehasping my personal residence to convert the space into a residence and office. This was then renovated again in 2020 with a new bamboo-structure building added to its eastern side under the name Guha. Guha originates from a Sanskrit word that means 'cave', but it also alludes to the war-god Kartikeya. Guild consists of the OMAH Library, the dental clinic run by my wife, and the residence, while 'Guha' consists of a studio known as Guha Bambu that I use as the studio office. This final element ofthe project is a manifestation of my personal desire to endlessly explore form and ideas. In this building, I have experimented with tectonics since 2015 to create its 'grammar', and this was completed over the course of multiple phases. In each phase - from concrete, wood, metal, masonry, and bamboo - there is a structural grammar that matches with each respective material. When I was performing these steps, I tried to resolve any problems by integrating form, space, and the architectural system while also ensuring consideration of other possibilities in terms of architectural formation.

Park: Difficulties always arise during the initial design conception and its subsequent development. What ignited your inspiration here or led you to create this architectural form?

Realrich: Like other architects, I was inspired by artwork. There are three figures from twentieth-century Indonesian art here that provided the greatest influence: the artist Sindu Sudjojono (1913 -1986), who approached art as a discourse; the realist painter Basuki Abdullah (1915 -1993), who set his technical knowledge as a background to his work, and the artist Koesoema Affandi (1907 -1990), who focused on the gestures of the body and expressions of beauty. I believe that the point at which the ideologies of these three masters meet cuts across any perceived boundaries between art and architecture. This is what Sudjojono meant by his concept 'Jiwo Ketok'. This concept, which refers to the idea of a visible soul, proceeds from something massive to something minute in architecture, and develops through the perfecting of working details throughout the entire design process. These details are the result of lengthy experience; one learns by encountering numerous failures and experiments. My father once told me to 'go back to the basics' when I was lost and unable to find a solution to a design problem. What he said helped me to realize where one is, and how one must build a stable foothold. By gathering, the means of overcoming such h experiences, I was able to establish my tectonic grammar. With this as background, I worked on the residential and office building while considering its variability and flexibility for future renovations and expansions.

Park: I think the elements you just noted are so accurate and so visible in Guild and Guha. The project was built in a remote residential area in Jakarta. What are the characteristics of this neighborhood and its surroundings?

Realrich: The building is in a residential district that was developed in the 1990s. Towards the south, rows of functionally- designed houses with the odd glimmer of Mediterranean design can be found, while towards the north, there is a mosque, single-floor boarding houses, cafes made of temporary structures, street kiosks, and food catering businesses that can be accessed via a narrow road. Other than the differences caused by the gap in the conditions between the north and the south, there is also an inclined slope of about 2m towards the south. The western area, where an access road is located, is also prone to flooding when it rains for more than 15 minutes.

Park: The residence and the office are located at the same building in the Guild. How did you separate and connect the functions required of the residential and office spaces? Moreover, the public workroom in the lobby appears to merge with the entrance, library, exterior pond, and swimming pool, etc.

Realrich: The positioning can be largely divided into two areas. Since the workspace is on the lobby floor, the residential space was placed upstairs. There is a small terrace at the western main entrance. Across this space for receiving guests, two doors can be found. One door leads to the office and the living room, while the other leads to the library and the central courtyard. The library, of an elongated shape alongside the western wall, is connected to the interior corridor that connects the pond to the courtyard, as well as to the pantry and dining hall for the staff on the first floor. The pantry and dining hall for the family, however, is on the second floor, while a circular window that covers the entire wall is focused on the pond and the courtyard. The circulations of the working area and the residential area are kept separated thanks to the terrace at the main entrance, but they are all also linked through the courtyard.

Park: In reference to what you said about the courtyard as the connecting hub for the programs-it seems to me that the connection between the exterior and interior that often appears in Indonesian architecture is greatly affected by the climate conditions. Along with the matter of climate the exterior view from the interior is quite deliberate. What were your intentions and your thoughts behind this in relation to the specific climate conditions?

Realrich: There is a street at about 200m away from the building, and the descent to the water channel is too small. Moreover, its level is lower than the other streets in the area, and water cannot flow out of it. Because of this, the design for the Guild was conducted according to a focus upon the prevention of local flooding due to its wet climate. Also. in response to the three 12m-high trees surrounding the southern building, I designed the building with the aim of creating an environment that suits its given micro-climate. The same intention was replicated in Guha. Selected wild plants, frangipani trees, and grass -plants that are easy to manage -were chosen to organize the landscape. This was not merely to create a green space for aesthetic appreciation, but to realize an actual 'micro-climate'. It was a kind of an experiment to create a beautiful environment while trying to reduce the surrounding temperature. As time passed, various plants such as vines that produce shade and block the heat were also introduced. Gradually, the Guild turned into a forest, a pond was introduced, and its public library was designed to cater to further gradual modifications.

Park: The Indonesian design of the courtyard, with the window at the façade and the form of the skylight, is very impressive. It seems like there is a lot of research behind these features in terms of structure-how were they developed?

Realrich: This is an important question. The forms of these elements that you mention were inspired by ancient masonry structures such as the Batujaya temple in Kerawang and the Borobudur temple. These structures are mesmerizing for three reasons: first, the architectural expression in the ancient creative technique; second, the bold expression that results from the structure's pursuit for its unique identity; third, these works propose a multi-directional discourse that paradoxically creates harmony between themselves and their surroundings while expanding their boundaries. Such properties were reformed and reapplied to repetitive forms that fit our given situation during the project design stage. Natural light was drawn into the building, and wind paths were introduced. While ancient design elements can be experimental, I assumed that it would nonetheless help to connect Realrich Architecture with its wider public. All simple and circular forms -a tectonic grammar, as adapted material properties, and as things that I feel and make and make and feel in reverse -are derived from the region's traditional culture and climate.

Park: Not only the skylight, but also the many experimental elements around the building add to this sense. What roles do each of these elements play, and for what purpose were they applied to the residential and working spaces?

Realrich: We didn't create doors of different sizes designed for efficiency and aesthetics, choosing instead to insist upon the same design throughout the entire project. We conduct our research by first observing and reviewing the floorplan and familiarizing ourselves with its details. Through this method, we make decisions continuously regarding these details during and after the project itself. When deciding on the frame, there were some criteria given in terms of choosing the details under the three parameters of pattern, force, and concept. In this work, eight materials consisting of concrete, masonry, wood, bricks, plastic, glass, metal, and bamboo were used. As each material possesses its own unique properties, the aim of the project was to create a new concept regarding the detail work category for each material. We decided to use local materials to reveal the diversity of architecture via optimized design while connecting the local climate and culture with sustainable architecture.

Park: Six long years have passed since you

began studying the various contents of this site and finally completing the

project. I assume that there are various attempts and thoughts that you've

showcased in other projects that got mixed in somewhere -if there is a concise

summary of what you've conceptualized or contemplated thus far, could you

please shed light on it?

Realrich: 'Tectogram' is a poetic language that we derived by compiling all our experiences of architectural success and failure. Jiwo Ketok, which I mentioned earlier, is a concept that we developed from the tectogram. When I visit the traditional temples to which I referred earlier, I repeatedly ask myself how and why the resulting construction fulfills its initial design ambitions. This could also be summarized in two expressions: 'design methodology' and 'design implementation'. For to evolve, the two must undergo transformations. via continuous development. Both are elements that need to be standardized, planned, and reevaluated. Implementation expands into the world of tectograms, and methodology leads one into the world of methodgrams.

Park: I'd like to ask you about the OMAH Library. Various educational programs are being held, and I suppose this also applies to this building. Who was the intended target audience of these programs?

Realrich: After finishing the final evaluation at the architecture department of lnstitut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, about 20 students approached me and applied for internships at our office. I wanted to take them all, but there was not enough space. I brought up this concern with my parents, and we decided to build a pavilion at one unused corner in the garden. Here, we could discuss and share architectural experiences and knowledge with the interns. After the students returned to the institute, I decided to build the OMAH Library. As I moved the pavilion to the adjacent site and built a library within the building, more locals came to use the facility. I want to develop my neighborhood and nurture it into a beautiful place. I want to make friends with whom I can debate and share a common understanding in the importance of architecture.

Park: The pandemic situation is changing the lives of people worldwide. There have been many changes to life patterns and human relationships. What kind of changes have taken place in Indonesia, particularly given its high rate of infection and death from Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19)? How is the architectural scene responding to this?

Realrich: I'm keeping an eye on the phenomenon with the long-term changes to our era in mind. I researched the impact that the pandemic situation might bring about and have come up with three possibilities: first, that architectural projects would be greatly slowed down; second, that there might be integration between decentralized studio teams and production teams; third, a new normal would be reached and there would be a need to evaluate its culture and conditions. To create a healthier environment, there needs to be more projects that improve actual quality of life―and by that, I mean the projects that seek a middle ground between the high-rise and high-density urban life of our cities. Regarding the search for urban development within an era of a new density concept and a new urban environment, there is a need for architects to step up and make their voices heard.

Park: With its first-generation architects born in the 1920 -1930s, and its second-generation architects born in the 1940 -1950s. Korean contemporary architecture is now furthered by activities of third-generation architects born in the 1970 -1980s. Historically, the question regarding identity and style has always been the matter of debate for each generation. Stepping aside from this philosophically heavy question regarding perception and historicity, however, there is now an interest or trend formulating towards architectural techniques themselves and the various approaches to view architecture as object.

Realrich: Identity is also an issue that remains pertinent to Indonesian architects. Many young architects try to define their unique aspect through ornamentation, and I think this represents a process that leads from shallower thinking to deep and profound contemplation. An architecture critic YusufBilyarta Mangunwijaya (1929 -1999) once commented of the Young Indonesian Architects Forum in the 1990s that it lacked a holistic concept and was merely interested in playing with forms without dealing with the needs of social residences or social issues. Presently, Indonesia is rapidly growing in terms of its development. There is a high demand for public and private residences, and with this there is a sustained growth in the construction and architectural industries. A new architectural law was implemented in 2017 to respond to this rising demand, and the number of registered architects has increased by 7,000 from 18,000 in 2018. The task is then to guide these new architects to build a healthier industrial ecosystem in their regional societies.

Park: The world architecture trends are still considered to emanate from Europe or the US, but cultural change means that there is a migration towards Asia. I think that the historical and cultural foundations of Asia are the reason for this growing trend. As an architect in Indonesia, what problems remain to be tackled considering this challenge? How have your experiences in Australia, England, and Singapore affected you and your works?

Realrich: The undergraduate programs in Indonesian universities mainly focus on the technical skills behind architectural design. At the architectural offices overseas, however, they ask for critical thinking and creativity to propose new methods and innovative theories for producing architecture. This training, in critical thinking and creativity, during my overseas education and work experience led me to view my home traditions and history in a new way. The postcolonial period in which we live now was preceded by the colonial period and the pre-colonial period. Indonesia is a country with a rich cultural diversity of approximately 300 different tribes that now exist in harmony with the more modern aspects of life. Perhaps in the industrial standards established in a distant future, it might not be as important to connect new technologies with traditional artisanship. However, here at Realrich Architecture, we believe that it is 'humans' who form culture. There will be something unique created between culture and the architect as a human being. I have always contemplated how to be both critical and creative when integrating architectural techniques with artisanship. As such, we came to redefine our roles as a 'rahayu' (bridges) that connect experiments with inspirational materials to tradition. Contemporary architectural trends in Indonesia are characterized by a core problem in the way one understands the context when defining the design issue or locating a starting point. Our task is to go beyond the old critical methods and to revolutionize with freer means of thinking without losing touch with our tradition. The fundamental solution for this would be a focus on climate and culture. As we now face a future of pluralistic approaches, we constantly think about how to integrate technique and architecture, and what approaches we should employ.