앤디라흐만 아키텍트_ 라흐만 아프릴리안토

누산타라 건축과 현대건축의 연결

앤디 라흐만아프릴리안토(라흐만): 2000년대 이전에 인도네시아는 고유의 건축적 정체성을 잃어버리는 위기를 겪었다. 그러나 지난 10년 동안 인도네시아의 젊은 건축가들은 정체성의 중요성을 깨달으며 지역의 건축을 탐구하고 발전시켜왔다. 이러한 자각은 인도네시아가 ‘누산타라(Nusantara) 건축’이라는 서양 건축에 필적하는 독창적인 건축 역사를 가지고 있다는 사실에 근거한다. 우리는 이를 바탕으로 현재와 미래의 문제에 답하기 위해 누산타라 건축을 끊임없이 연구하고 있다.

라흐만: 우리는 아시아가 문화와 건축에서 굉장히 강한 역사적, 철학적 뿌리를 가지고 있다고 생각한다. 이것이 서구권, 특히 유럽이나 미국과 다른 점이다. 나의 스승인 요세프 프리조토모(Josef Prijotomo)는 "누산타라 건축은 철학, 과학, 건축 지식을 기초로 하며, 또 여기에서 유래한 일종의 ‘지식으로서의 건축’이라고 했다. 또한 전통건축은 보다 앞선 시기부터 존재해왔던 인류학이나 민속학 같은 문화적 지식에 근거하는 반면, 누산타라 건축은 건축적 지식(건축적 시스템과 발전)에 기반하기 때문에 단순한 전통건축과는 개념적으로 차이가 있다고 설명했다. 누산타라 건축은 상호 협력적인 시스템이자, 건축물인 동시에 환경과 사회 그 자체를 일컬으며 인도네시아 기후의 특성을 반영한다. 바람이 통하는 벽 (실내에 적절한 공기 순환을 유도하는 벽)과 같은 기술적인 콘셉트의 적용 등을 예로 들 수 있다. 우리는 특히 디자인적으로 누산타라 건축을 탐구하고 발전시켜왔다. 건축의 디자인과 외형은 현대적인 맥락을 따르는 동시에 정체성과 관련해서 여전히 누산타라 건축의 강력한 DNA를 작품 활동에 적용하고 있다.

라흐만: 나는 인도네시아 수라바야 스풀루 노웸버 공과대학교에서 건축을 전공했다. 2004년에 졸업한 이후에는 수라바야에서, 현재는 수라바야 남쪽에 위치한 인구 200만 명의 도시인 시도아르조(Sidoatjo)에서 활동하고 있다. 대학 교육은 나의 사고와 학습 프로세스에 굉장히 큰 영향을 미쳤다. 특히 누산타라 건축의 현대화에 앞장선 이론가 중 한 명인 프리조토모 밑에서 공부하면서 큰 영향을 받았다. 그는 현대적인 누산타라 건축에 대한 지원과 지식 전수에 힘써왔다.

라흐만: 수라바야에는 주로 통용되는 자바어인 아 렉 수로보요(Arek Suroboyo)나 캉크루칸(Cangkrukan)이라는, 지역 내에서 통용되는 일상적이면서도 독특한 문화가 있다고 느꼈다. 자카르타는 인구가 많다 보니 타인을 만날 때 약간 폐쇄적인 경계의식이 있는데 수라바야는 인간관계나 사회적 연결을 위해 서로 대면하는 일이 훨씬 수월하다.

박: 인도네시아 건축대학에서 누산타라 건축을 가르치는 부분은 한국에도

시사하는 바가 크다. 사실 누산타라 건축의 현대화는 기술 발전과 함께 세계화의 영향 중 하나라고 생각한다. 아시아 대부분의 국가들에서 타국의 건축을 쉽게 접할 수 있다 보니 전 세계적으로 서로가 서로를 복제하는 ‘건축의 계열화(integration of architecture)’가

더 빨라지는 느낌이다. 그러다 보니 아시아 국가들은 자신만의 정체성에 관심을 가질 수밖에 없다. 이런 맥락에서 누산타라의 발전과 함께 건축적으로 고민하는 최근 이슈는 무엇인가?

라흐만: 인도네시아의 건축 경향은 모던한 스타일을 구사하는 다른 아시아 건축과 크게 다르지 않다. 하지만 최근 주거 건축의 디자인 방식은 변화하기 시작했고, 나라별로 문화와 역사, 재료와 관련한 지역적 가치를 향해 다시 회귀하고 있다. 이러한 관점에서 인도네시아 건축은 우수한 지역적 정체성을 이끌어 나가기 시작했다. 이는 누산타라 건축을 현대적으로 발전시키려는 우리 사무소의 비전과도 결을 같이한다. 우리 팀은 건축 과정에서 설계 인력과 현장에서 작업하는 장인 모두가 이익을 얻을 수 있도록 수공예적 협력 관계를 맺는다. 일련의 과정은 우리 땅에서 누산타라 건축이 얼마나 소중하고 가치 있는지 중요성을 일깨워주며, 궁극적으로 건축을 통해 ‘신의 발자취를 따른다’는 강한 종교적 신념을 불어넣는다.

라흐만: 보토주택의 건축주는 시도아르조의 건설 사업가다. 그는 먼저 인도네시아의 여러 건축가들에 대해 조사한 다음 최종적으로 우리에게 작업을 의뢰했다. 당시 건축주는 벽돌을 사용해 집을 리노베이션 하길 원했다. 우리가 벽돌을 사용해 지었던 자바 동부 지역의 프로젝트를 보고 흥미를느꼈고, 건물 외형에 벽돌을 그대로 노출하겠다는 큰 기대를 가지고 있었다. 또한 어떻게 하면 인도네시아의 색깔을 집에 녹여낼 수 있을지 고민하고 있었다. 우리는 그의 열정과 생각이, 현대적인 디자인과 조화를 이루는 인도네시아적인 건축을 탐구하고 발전시키고자 하는 우리의 비전과 맞닿아 있다고 느꼈다. 그래서인지 이 집을 보는 사람들마다 인도네시아적인 집이라고 이야기한다.

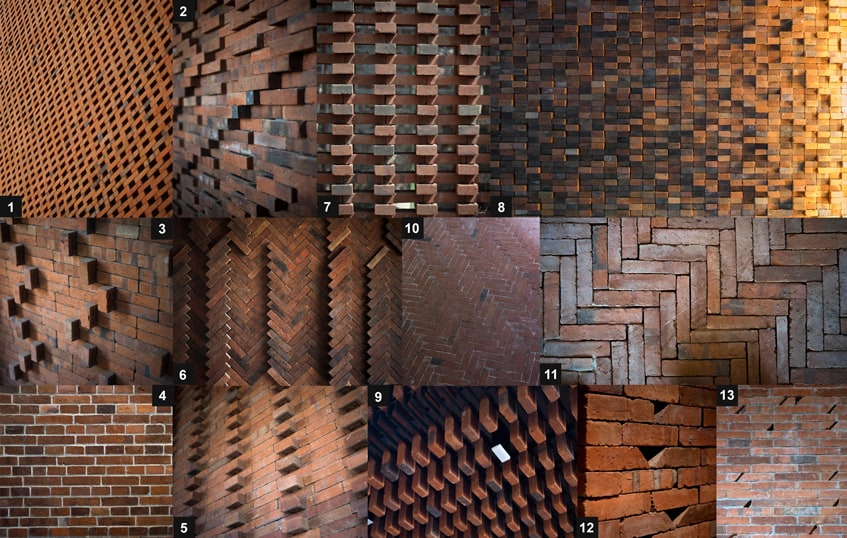

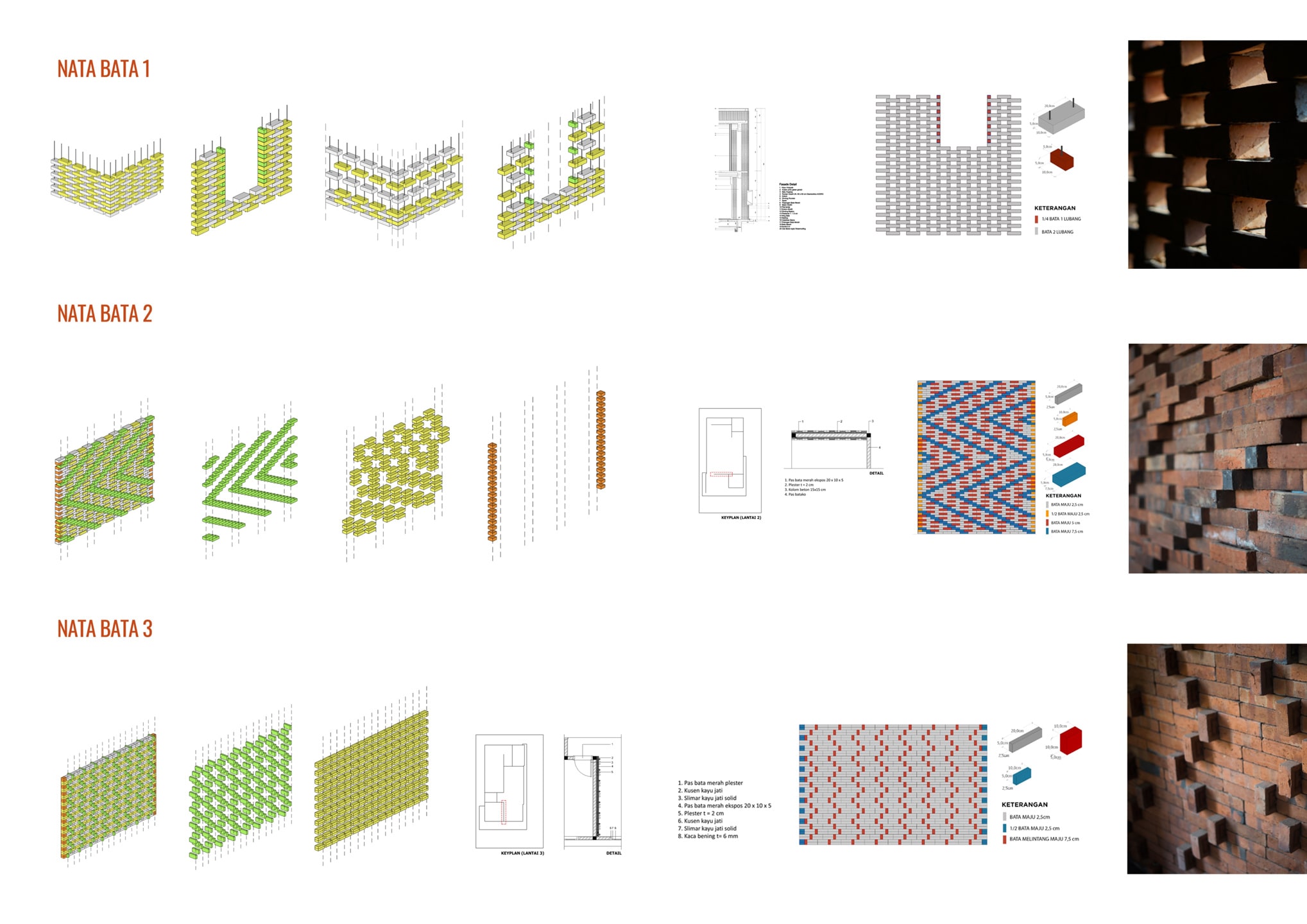

라흐만: 우리는 벽돌의 형태를 표현하는 방법으로 사각형의 단순한 매스 디자인을 선택했고, 벽돌은 보토 주택의 DNA라 할 수 있다. 또한 게덱(Gedek, 대나무 짜임벽)이라는 인도네시아 전통가옥의 요소를 차용해 숨 쉬는 개념의 벽을 만들었다. 게덱은 집의 프라이버시를 보호하고 실내 온·습도를 낮추고 공기 순환과 채광을 조절한다. 우리는 이러한 게덱의 특성을 보토주택 외피에 적용했다. 단, 차이점은 재료다. 대나무가 아닌 벽돌로 짜임벽을 만든 것이다. 보토주택이 전형적인 지중해식 양식의 이웃집들 사이에서 개성 있는 독창적인 미를 갖는 이유다. 이 집은 주변 환경을 잘 이해하고 분석하여 인도네시아의 기후와 문화적인 맥락에 대한 답을 제시한다.

라흐만: 벽돌 조적 방식 외에도 게뵥(Gebyok)과 게덱과 같이 인도네시아인, 특히 자바인 주택의 특징적인 몇몇 요소들도 현대적으로 변환하여 사용했다. 게뵥은 자바 지역 고유의 가구로, 대개 고품질의 티크에 자바의 조각 방식을 적용해 만든 실내 파티션이다. 게복의 역사는 16세기 칼리냐맛 여왕 시절로 거슬러 올라간다. 그가 통치한 시기에 탄생한 게뵥은 복잡하고 아름다운 조각으로, 심미적이고 윤리적인 사상과 감성을 담은 하나의 완결된 작품이다. 게복은 사용자들에게 영적인 메시지를 전달한다. 게뵥의 조각은 인간 삶의 목적을 의미하는 ‘상칸파라닝 두만디’(삶의 기원과목적), 조화, 번영과 평화를 묘사한다. 특히 게뵥의 조화는 자연과 조화를 이루는 삶의 중요성을 의미한다. 게뵥은 엄선된 재료와 전문가의 기술을 필요로 하기 때문에 이를 갖춘 집은 평범한집이 아니라 특정한 목적을 위해 만들어진 집이라 할 수 있다. 또 다른 방식인 게덱은 일종의 대나무 짜임벽으로 주택의 벽, 벽 마감, 천장 등에 흔히 사용된다. 게덱의 디자인을 활용해 가방이나 샌들, 모자를 만들기도 한다. 흥미롭고 개성 넘치는 디자인을 지닌 게덱은 대나무를 엮는 기술과 집중력이 필요하다. 이 또한 지속가능한 건축 재료라고 생각한다.

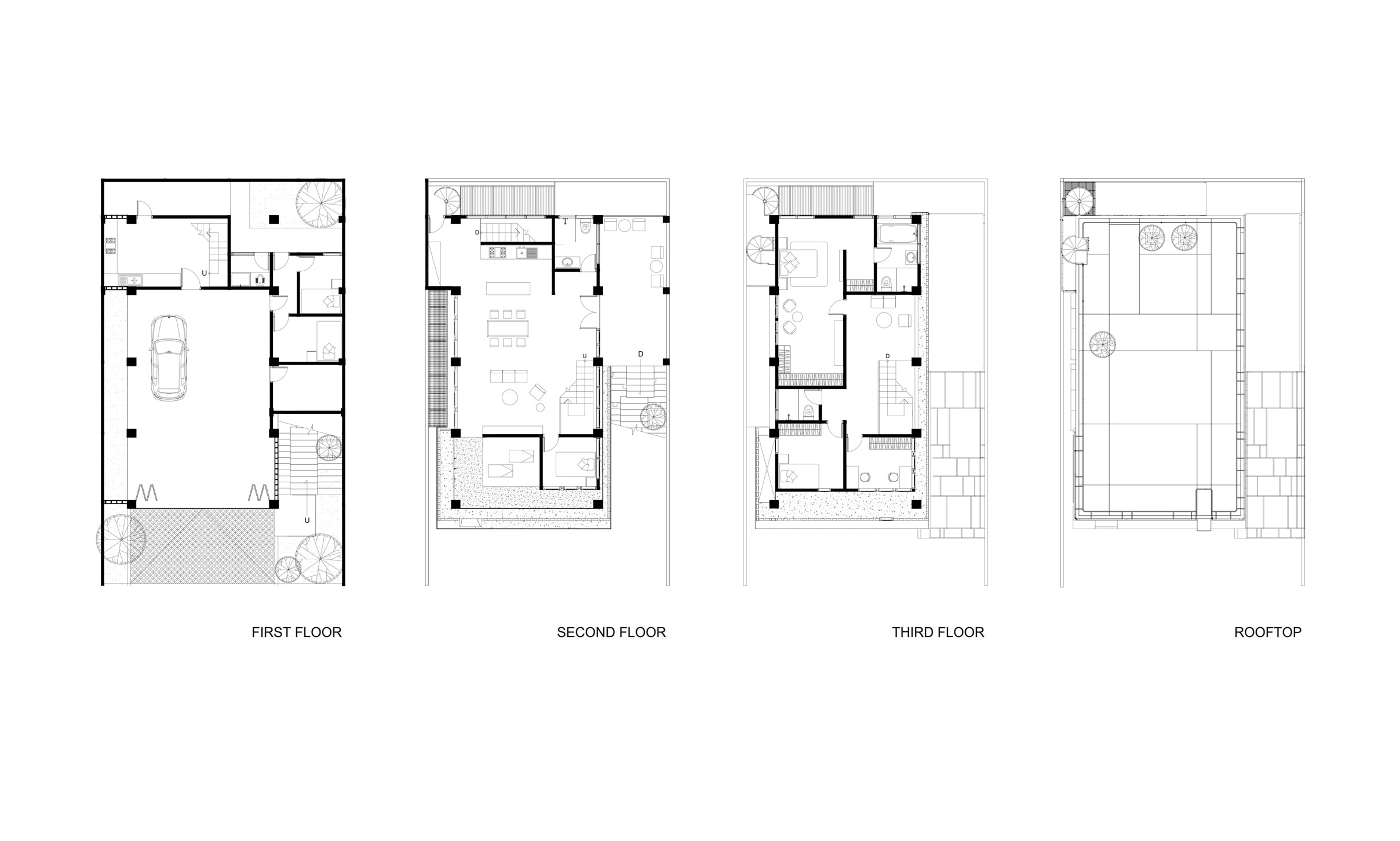

박: 보토 주택 내부로 들어가면 가장 먼저 1층의 넓은 현관을 마주하게 된다. 한국 주택에서는 이러한 공간을

주차장용도 외에는 거의 볼 수 없다. 어떤 용도의 공간인가? 이곳과

연결된 1층의 여러 실들은 외부 공간과 어떤 관계가 있는지 궁금하다.

라흐만: 현관의 야외 공간은 건축주가 100명 이상의 사람들이 모여 정기적으로 코란을 낭독하는 공간이 필요하다고 해서 만든 것이다. 공용 실과 차고 역할도 겸하며 공용 실과 연결된 창고에 낭독에 필요한 장비들을 수납한다. 가정부들이 쉴 수 있도록 뒷마당 쪽으로 창을 낸 가정부 전용 실들이 있다. 1층의 주방은 공용실, 가정부 전용실과 하나의 영역으로 연결된다. 인도네시아 인구의 대부분이 무슬림이라 집 안에 기도실은 필수적이다. 이 주택에서는 단순한 기도실 외에도 대중교육 목적을 겸하기 때문에 굉장히 중요한 공간이라 할 수 있다.

라흐만: 2층에는 손님맞이를 위한 반외부 테라스가 있는데, 손님들은 이곳을 통해서만 집으로 들어갈 수 있다. 팬데믹 상황과 뉴노멀 시대에 매우 적절한 공간이라고 할 수 있다. 가족실, 부엌, 일하는 공간, 기도실과 같은 덜 사적인 영역은 2층에, 침실 같은 사적인 공간은 3층에 배치했다. 평면구성에서 보토 주택은 개방된 공용 응접실인 펜도포(pendopo), 공적 공간과 사적 공간 사이의 전이 공간인 프링지탄(pringgitan),사적인 휴게실인 오마 달렘(omah dalem)과 같은 전통가옥의 공간 위계에서 영감을 받아 디자인했다. 제한된 부지 안에서 복잡한 요구에 맞춰 공간적 타이폴로지의 위계를 그대로 유지하기 위해 이를 수평적인 것에서 수직적인 것으로 치환한 것이다

라흐만: 우리가 보토 주택에서 보여주고 싶었던 또다른 주제는 방금 말한 수공예의 장인정신과 벽돌이라는 재료 자체였다. 우리는 우리의 프로젝트와 사무소가 위치한 자바 동부 지역에서 14세기 마자파 힛(Majapahit) 시대부터 사용되어온 전통적인 조적 건축을 보전하려 했다. 자바 동부의 벽돌 품질은 이미 세계적으로도 잘 알려져 있다. 보토 주택은 마자파 힛 시대에 지어진 사원들과 가까운 곳에 위치하며, 수무르 사원(SumurTemple)과 파리 사원(Pari Temple)은 불과 4km 정도 거 리에 있다. 우리는 이 두 사원의 조적 방식에 대해 연구했다. 그러면서 열세 가지의 새로운 조적 방식을 고안했고 보토주택에 이를 적용하고 싶다는 우리 의견에 건축주도 동의했다. 주택에 사용된 장식은 벽돌, 나무, 엮은 대나무, 시멘트 타일과 같이 모두 전통적인 재료들을 이용해 만들어졌다. 우리는 궁극적으로 현대에 이르러서 점차 사라져가고 있는 수공예가들의 장인정신을 다시금 끌어올리고 지역 장인들의 명맥이 유지되도록 돕고자 했다.

라흐만: 우리는 건축가의 전문성이 장인들보다 더 뛰어나다고는 생각하지 않는다. 그래서 장인들과 파트너십을 구축하고 서로에게 유익이 있도록 협업한다. 건축가들은 기술적인 부분과 이를 현장에서 어떻게 적용할지 장인에게서 배우며, 장인들 또한 경험해보지 못했던 디자인 방식을 우리를 통해 접할 기회를 갖는다. 이러한 협력적인 관계는 서로를 평등하게 존중하는 누산타라인들의 사고방식에서 기인한다.

라흐만: 보토주택은 우리가 섭외한장인과 건축주 쪽에서 섭외한 장인들이 함께 작업한 결과물이다. 건축주쪽의 장인들은 구조적인 부분들을, 우리 쪽의 장인들은 건축 디자인적 부분과 재료의 디테일한 적용을 담당했다. 이 프로젝트에서뿐만 아니라, 자바동부 이외의 지역에서도 그 지역의 장인들과 협업한다. 우리의 비전은 지속가능한 건축으로서 장인들이 꾸준히 존경받을 수 있게 전통적인 수공예에 대한 지식을 육성하고 현지 재료를 탐구하는 것이다. 이러한 논리를 위해서는 공사 기간 동안 발생하는 에너지와 비용을 최소화할 수 있도록 프로젝트가 진행되는 지역에 따라 장인이라는 인적 자원과 현지 재료라는 물적 자원이 뒷받침되어야 한다.

라흐만: 우리는 선조들이 구축한 누산타라 건축의 정신을 이어받아, 프로젝트마다 각지역의 특성과 문화적 뿌리에서 추출한 각기 다른 성격을 적용했다. 인도네시아는 사방(Sabang)에서 머라우케(Merauke)까지 수백 가지 유형의 전통가옥을 아우르는 풍부한 건축유산을 가지고 있다. 보토 주택은 재료사용, 문화적 특성, 기후에 대응하는 지역 맥락을 고려하여 설계되었고, 이러한 특이점들이 다양성을 발현시켜 여느 건축물들과는 다른 모습을 가지게 했다. 이러한 ‘다양성의 건축’이야말로 누산타라 건축의 핵심이다.

Andyrahman Architect_ Andy Rahman Aprillianto

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN NUSANTARA ARCHITECTURE AND CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE

Andy Rahman Aprillianto graduated from

Institut Teknologi Sepuluh November Surabaya (ITS). After graduation, he, and

Abdi Manaffounded Andyrahman Architect in 2006 and has long been influential

upon the Indonesian architecture community. He is actively participating in

various architectural events and exhibitions, such as the Indonesian

Architecture Public Exhibition in Japan and the Netherlands, and Omah Boto,

which he designed, was selected as one of the 50 Best Architectural Projects

and The 50 Best Houses of 2019 by Archdaily.

Park Changhyun (Park): Southeast Asian

architects have begun to speak with greater urgency about locality and

originality in response to globalization. What, do you think, is the foremost

focus of young Indonesian architects?

Andy Rahman Aprillianto (Rahman): Before 2000, Indonesia experienced a crisis where we lost our own architectural identity. However, with the passing of the last decade, the younger generation of Indonesian architects has begun to try to realize the importance of architecture that has an identity, by exploring and developing the local architecture of our own nation. This awareness begins with the understanding that Indonesia is a nation that has a distinctive architectural history equivalent to that found in western architecture, Nusantara architecture. This awareness is what prompts us to continue exploring the legacy of Nusantara architecture to be able to address present and future problems.

Rahman: We study history from the understanding that Asian people have strong historical and philosophical roots in terms of their culture and architecture, one that is very different from the West, especially Europe and America, and asserting that we possess a different architectural genealogy to them. Based on the statement made by Josef Prijotomo in 2002, 'Nusantara architecture is architecture as a knowledge based on and derived from philosophy, science and architectural knowledge'. He also stated that Nusantara architecture is not traditional architecture'2, it exists in the realm of architectural knowledge (architectural systems and development) while traditional architecture refers to cultural knowledge (anthropology and ethnology). Nusantara architecture is a system of cooperation: not only formed of buildings but also of environmental and societal concerns.'3 Nusantara architecture has an architectural character that responds to a climate characterized by two seasons in Indonesia, evidenced by the application of one technical concept in the form of a breathing wall (a wall that is able to create a good circulation system in a room). In terms of identity, they continue to apply the strong DNA of Nusantara architecture, but the designs and visuals are sensitive to our contemporary context.

Rahman: As a graduate I majored in architecture at institute Teknologi Sepuluh November Surabaya. After I graduated in 2004, I began practicing architecture in Surabaya and now in Sidoarjo, a city located south of Surabaya with a population of two million. My education at the university greatly influenced my thinking, ways of learning and problem-solving process, especially thanks to one of the professors, Josef Prijotomo, who focuses on the development of Nusantara architecture. He is also committed to supporting the knowledge base related to contemporary Nusantara architecture.

Rahman: In my opinion, there are some unique everyday things in the city of Surabaya, such as the typical Javanese language of Arek Suroboyo, and a very popular social culture, namely Cangkrukan-the culture of hanging out with friends, relatives, or anyone through random conversation topics regardless of standing or shared experiences. In this city, it is much easier to greet each other, and we are encouraged to broaden our sphere of acquaintance and connections compared to that in a city like Jakarta, with its larger population and boundaries to socializing with other people.

Rahman: The general tendency of Indonesian architectural styles is almost the same as architecture in other Asian countries, where most houses adopt distinct modem architectural styles. However, in recent years the development of home design has begun to change, returning to regional values of the material, culture and history that exist in each of these countries. Indonesian architecture has also begun to lead to architecture of a local Indonesian identity. This is in accordance with the vision of our architectural studio to develop contemporary Nusantara architecture. In architectural practice, we work with architectural craftmanship in which through the design and construction process we create mutually beneficial cooperation between us as a team of architects and craftsmen as executors in the field. That is what makes us aware of the importance of Nusantara architecture as a worthy architectural form on our terrain, Indonesia. This identity ultimately expresses the spiritual conviction, 'Architecture as a Way to Return to the Path of God’.

Park: We would like to know more about the

background to Omah Boto. What did you discuss with the client when embarking

upon the project?

Rahman: The client of Omah Boto is a construction entrepreneur in Sidoarjo. Before hiring us, he had studied many architects in Indonesia, and finally selected me as the architect to design his house. We happen to live in the same city, Sidoarjo. At that time, the client wanted to renovate his house using bricks as the primary material. He had high expectations that the brick material would be exposed, because he had admired our projects in East Java that use bricks. During the design discussion process, the owner expressed a desire to present Indonesian architecture through modem and contemporary designs. Based on these discussions, we know that he is driven by the same passion as our own to explore and develop architectural designs that represent the character of Indonesian architecture, but through a modem and contemporary perspective. Therefore, every single person who visits this house tends to assume that it is a typical Indonesian house.

Rahman: We took a simple box design to represent the shape of a brick. Bricks are used as the cells and DNA in Omah Boto. In addition, we took the principle of a breathing wall from the many examples in traditional houses of Indonesia, namely the Gedek (a woven bamboo wall). Gedekfunctions to maintain privacy of activities taking place in the house and to circulate air and sunlight so that the room is not hot and humid. We applied Gedekto Omah Boto's skin. The difference is that we didn't use woven bamboo, but woven bricks. This is what makes Omah Boto look 'extraordinary' in comparison to the neighboring houses of classical and Mediterranean architectural styles. Omah Boto could be thought to criticize its surrounding context, while also built in answer to local climate conditions and the cultural context.

Rahman: Apart from the knowledge of brick tectonics, Omah Boto also has other elements familiar to the homes of many Indonesians, especially the Javanese, namely Gebyok and Gedek. Gebyokis a typical piece of Javanese furniture in the form of a room partition which generally features Javanese carvings and is made of high-quality teak wood. The history of Gebyok can be traced back to the life of Queen Kalinyamat, the third king of the sixteenth-century Demak Sultanate. During the reign of Queen Kalinyamat, the Gebyok was invented and was swiftly understood as a masterpiece with its intricate and beautiful carvings. Gebyok reflects aesthetic and ethical thoughts and feelings. The carvings on the Gebyokdescribe the purpose of human life, Sangkan Paraning Dumadi (origin and purpose of life), harmony, prosperity, and peace. The harmony of the design of theGebyok reveals the importance of living in harmony with nature. A house that uses a Gebyok may not be an ordinary house but a preferred house, because to create a Gebyok requires selected wood and the best experts of its time. Gedek is a woven bamboo technique commonly used in house walls, wall coverings, and ceilings, and throughout its evolution Gedekalso also been used to make many things from bags, sandals, to caps. Making works from Gedek requires skill and concentration to weave bamboo into interesting and unique motifs. The presence of the Gedek is that of a sustainable building material.

Rahman: The first floor at Omah Boto functions as a garage and communal room that accommodates the client's needs, such as routine recitation activities with a capacity of more than 100 people. Then there is a warehouse as a storage area for recitation equipment connected to the communal room, and a housemaid's room that has a window facing the back garden, to make this space as comfortable as possible. The kitchen on the first floor is connected to a common room and a private room for the housemaid. Prayer rooms are essential at home because most of Indonesia's population is Muslim. In addition to the simple prayer room, this house is a very important space because it serves both public educational purposes. On the second floor there is a semi-outdoor terrace for guests, where guests can only reach their spaces through this area. Therefore, it is very well suited to the demands of the 'new normal' in the age of the Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19). The second floor also contains semi-private rooms such as the family room, a dining room, a work room, and a prayer room. The third floor contains private rooms, such as the master bedroom and several other bedrooms. In the plan composition, Omah Boto developed from the established hierarchy of a traditional Javanese house layout, namely the pendopo room (public space for receiving guests, communal spaces), pringgitan (transitional room between public and private spaces) and omah dalem (private space for resting). The need for complex spaces and the restrictions incurred by the size of the site resulted in a spatial typology that runs from horizontal to vertical, but hierarchically remains the same.

Rahman: Another theme that we want to explore at Omah Boto is the artisan spirit of handicraft and the nature of the materials, here primarily the bricks. We tried to preserve the existing tradition of brick architecture in East Java, a method cultivated since the fourteenth century Majapahit era in the eastern Java region, where our projects and studios are located. The bricks in East Java are known worldwide for their high quality. Omah Boto is located close to temples built during the Majapahit era and Sumur Temple and Pari Temple are only about 4km away. We studied the method of steering the two temples. In the meantime, we came up with 13 new methods of manufacture, and the architect agreed with our suggestion that they should have applied them to the Omah Boto project. The ornaments used from Omah Boto are traditional materials, bricks, wood, woven bamboo, and cement tiles. We wanted to lift the spirit of craftmanship and to support local material craftsmen survive at a time in which their industry is increasingly fading from view.

Rahman: Professionally speaking, we don't think the expertise of architects is better than craftsmen. Therefore, we build partnerships with artisans and collaborate to benefit each other. All we as a team of architects can do is learn about technical things and how to solve them in the field. Likewise, through us craftsmen can learn the means and methods of design never experienced. This cooperative relationship stems from the mindset of the Nusantar people which focuses on mutual respect.

Rahman: Omah Boto is the result of the collaboration between the craftsmen from us and the client. Architectural craftsmen were responsible for structural parts, and our craftsmen were responsible for architectural design and detailed application of materials. In addition to this project, we collaborate with local craftsmen outside of East Java. Our vision is to foster knowledge of traditional handicrafts and explore local materials so that craftsmen can be constantly respected as sustainable architecture. This logic requires the support of human resources as craftsmen and physical resources as local materials, depending on the region where the project is being carried out to minimize energy and costs generated during the construction period.

Rahman: We inherited the spirit of Nusantara architecture built by our ancestors and applied the characteristics of each region and elements extracted from cultural roots in each project. Indonesia has a rich architectural heritage spanning hundreds of traditional houses, from Sabangto the region of Merauke. Omah Boto was designed to consider the local context of material use, cultural characteristics, and climate, and these peculiarities expressed diversity, giving it a different unique disposition to that of other buildings. This 'diverse building' is now at the heart of Nusantara architecture.

누산타라 건축과 현대건축의 연결

앤디라흐만 아프릴리안토는 인도네시아 수라바야의 스풀루 노웸버 공과대학교를 졸업하고 2006년 앤디라흐만 아키텍트를 설립했다. 이후 꾸준히 작업하며 인도네시아

건축계에서 영향력 있는 활동을 펼치고 있다. 그는 일본과 네덜란드 등에서 열린 인도네시아 공공건축 전시회와

같은 다양한 건축행사와 전시에도 참여했다. 보토 주택은 2019년에

아키데일리 '올해의 건축물 50’과 올해의 주택 50’에 선정되었다.

자앤디라흐만 아키텍트는 2006년부터 활동한 인도네시아의 젊은 건축가

그룹으로 자국의 문화 정체성에 관심을 두고 지속적으로 작업해왔다. 그들은 인도네시아의 기후와 찬란했던

중세 인도네시아 문화인 누산타라 건축을 현대화하고 발전시켜 고유한 언어를 구축하고 있다. 이들의 관심이

건축적으로 구현되는 과정에 대해 앤디 라흐만 아프릴리안토와 서면으로 이야기를 나눴다.

박창현(박): 동남아시아 건축가들은 이제 세계화에 대응해 지역성과 독창성을 이야기하기 시작했다. 당신이 생각하는 인도네시아 젊은 건축가들의 관심은 무엇인가?

앤디 라흐만아프릴리안토(라흐만): 2000년대 이전에 인도네시아는 고유의 건축적 정체성을 잃어버리는 위기를 겪었다. 그러나 지난 10년 동안 인도네시아의 젊은 건축가들은 정체성의 중요성을 깨달으며 지역의 건축을 탐구하고 발전시켜왔다. 이러한 자각은 인도네시아가 ‘누산타라(Nusantara) 건축’이라는 서양 건축에 필적하는 독창적인 건축 역사를 가지고 있다는 사실에 근거한다. 우리는 이를 바탕으로 현재와 미래의 문제에 답하기 위해 누산타라 건축을 끊임없이 연구하고 있다.

박: 누산타라 건축은 구체적으로 어떤 것인가? 인도네시아의 젊은 건축가들은 누산타라 건축을 어떻게 받아들이고 전개해 나가고 있는가?

라흐만: 우리는 아시아가 문화와 건축에서 굉장히 강한 역사적, 철학적 뿌리를 가지고 있다고 생각한다. 이것이 서구권, 특히 유럽이나 미국과 다른 점이다. 나의 스승인 요세프 프리조토모(Josef Prijotomo)는 "누산타라 건축은 철학, 과학, 건축 지식을 기초로 하며, 또 여기에서 유래한 일종의 ‘지식으로서의 건축’이라고 했다. 또한 전통건축은 보다 앞선 시기부터 존재해왔던 인류학이나 민속학 같은 문화적 지식에 근거하는 반면, 누산타라 건축은 건축적 지식(건축적 시스템과 발전)에 기반하기 때문에 단순한 전통건축과는 개념적으로 차이가 있다고 설명했다. 누산타라 건축은 상호 협력적인 시스템이자, 건축물인 동시에 환경과 사회 그 자체를 일컬으며 인도네시아 기후의 특성을 반영한다. 바람이 통하는 벽 (실내에 적절한 공기 순환을 유도하는 벽)과 같은 기술적인 콘셉트의 적용 등을 예로 들 수 있다. 우리는 특히 디자인적으로 누산타라 건축을 탐구하고 발전시켜왔다. 건축의 디자인과 외형은 현대적인 맥락을 따르는 동시에 정체성과 관련해서 여전히 누산타라 건축의 강력한 DNA를 작품 활동에 적용하고 있다.

박: 한국의 젊은 건축가들에게도 한국성이나 전통건축을 개인의 작업으로 연결하는 과정은 쉽지 않은 문제이다. 누산타라 건축에 관심을 가지게 된 계기는 무엇인가?

라흐만: 나는 인도네시아 수라바야 스풀루 노웸버 공과대학교에서 건축을 전공했다. 2004년에 졸업한 이후에는 수라바야에서, 현재는 수라바야 남쪽에 위치한 인구 200만 명의 도시인 시도아르조(Sidoatjo)에서 활동하고 있다. 대학 교육은 나의 사고와 학습 프로세스에 굉장히 큰 영향을 미쳤다. 특히 누산타라 건축의 현대화에 앞장선 이론가 중 한 명인 프리조토모 밑에서 공부하면서 큰 영향을 받았다. 그는 현대적인 누산타라 건축에 대한 지원과 지식 전수에 힘써왔다.

박: 수라바야는 인도네시아의 수도인 자카르타와 어떻게 다른가?

라흐만: 수라바야에는 주로 통용되는 자바어인 아 렉 수로보요(Arek Suroboyo)나 캉크루칸(Cangkrukan)이라는, 지역 내에서 통용되는 일상적이면서도 독특한 문화가 있다고 느꼈다. 자카르타는 인구가 많다 보니 타인을 만날 때 약간 폐쇄적인 경계의식이 있는데 수라바야는 인간관계나 사회적 연결을 위해 서로 대면하는 일이 훨씬 수월하다.

박: 인도네시아 건축대학에서 누산타라 건축을 가르치는 부분은 한국에도

시사하는 바가 크다. 사실 누산타라 건축의 현대화는 기술 발전과 함께 세계화의 영향 중 하나라고 생각한다. 아시아 대부분의 국가들에서 타국의 건축을 쉽게 접할 수 있다 보니 전 세계적으로 서로가 서로를 복제하는 ‘건축의 계열화(integration of architecture)’가

더 빨라지는 느낌이다. 그러다 보니 아시아 국가들은 자신만의 정체성에 관심을 가질 수밖에 없다. 이런 맥락에서 누산타라의 발전과 함께 건축적으로 고민하는 최근 이슈는 무엇인가?

라흐만: 인도네시아의 건축 경향은 모던한 스타일을 구사하는 다른 아시아 건축과 크게 다르지 않다. 하지만 최근 주거 건축의 디자인 방식은 변화하기 시작했고, 나라별로 문화와 역사, 재료와 관련한 지역적 가치를 향해 다시 회귀하고 있다. 이러한 관점에서 인도네시아 건축은 우수한 지역적 정체성을 이끌어 나가기 시작했다. 이는 누산타라 건축을 현대적으로 발전시키려는 우리 사무소의 비전과도 결을 같이한다. 우리 팀은 건축 과정에서 설계 인력과 현장에서 작업하는 장인 모두가 이익을 얻을 수 있도록 수공예적 협력 관계를 맺는다. 일련의 과정은 우리 땅에서 누산타라 건축이 얼마나 소중하고 가치 있는지 중요성을 일깨워주며, 궁극적으로 건축을 통해 ‘신의 발자취를 따른다’는 강한 종교적 신념을 불어넣는다.

박: 보토 주택 (Omah Boto)의 배경에 대한 간략한 설명을 부탁한다. 어떻게 시작된 프로젝트인가? 건축주의 요구 사항은 무엇이었나?

라흐만: 보토주택의 건축주는 시도아르조의 건설 사업가다. 그는 먼저 인도네시아의 여러 건축가들에 대해 조사한 다음 최종적으로 우리에게 작업을 의뢰했다. 당시 건축주는 벽돌을 사용해 집을 리노베이션 하길 원했다. 우리가 벽돌을 사용해 지었던 자바 동부 지역의 프로젝트를 보고 흥미를느꼈고, 건물 외형에 벽돌을 그대로 노출하겠다는 큰 기대를 가지고 있었다. 또한 어떻게 하면 인도네시아의 색깔을 집에 녹여낼 수 있을지 고민하고 있었다. 우리는 그의 열정과 생각이, 현대적인 디자인과 조화를 이루는 인도네시아적인 건축을 탐구하고 발전시키고자 하는 우리의 비전과 맞닿아 있다고 느꼈다. 그래서인지 이 집을 보는 사람들마다 인도네시아적인 집이라고 이야기한다.

박: 이 집의 인상을 결정하는 것은 벽돌 입면이다. 벽돌을 일정한 간격으로 띄워서 표현한 다공성은 인도네시아에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 방식인가? 건물 앞 도로나 옆집들과 관계를 비롯해 기후적인 특성도 고려했으리라 짐작되는데 여기에는 어떤 의도가 있었나?

라흐만: 우리는 벽돌의 형태를 표현하는 방법으로 사각형의 단순한 매스 디자인을 선택했고, 벽돌은 보토 주택의 DNA라 할 수 있다. 또한 게덱(Gedek, 대나무 짜임벽)이라는 인도네시아 전통가옥의 요소를 차용해 숨 쉬는 개념의 벽을 만들었다. 게덱은 집의 프라이버시를 보호하고 실내 온·습도를 낮추고 공기 순환과 채광을 조절한다. 우리는 이러한 게덱의 특성을 보토주택 외피에 적용했다. 단, 차이점은 재료다. 대나무가 아닌 벽돌로 짜임벽을 만든 것이다. 보토주택이 전형적인 지중해식 양식의 이웃집들 사이에서 개성 있는 독창적인 미를 갖는 이유다. 이 집은 주변 환경을 잘 이해하고 분석하여 인도네시아의 기후와 문화적인 맥락에 대한 답을 제시한다.

박: 게 덱에 대해 더 구체적으로 설명 부탁하고, 또 게 덱 외에 다른 전통적인 방식을 사용한 부분은 없나?

라흐만: 벽돌 조적 방식 외에도 게뵥(Gebyok)과 게덱과 같이 인도네시아인, 특히 자바인 주택의 특징적인 몇몇 요소들도 현대적으로 변환하여 사용했다. 게뵥은 자바 지역 고유의 가구로, 대개 고품질의 티크에 자바의 조각 방식을 적용해 만든 실내 파티션이다. 게복의 역사는 16세기 칼리냐맛 여왕 시절로 거슬러 올라간다. 그가 통치한 시기에 탄생한 게뵥은 복잡하고 아름다운 조각으로, 심미적이고 윤리적인 사상과 감성을 담은 하나의 완결된 작품이다. 게복은 사용자들에게 영적인 메시지를 전달한다. 게뵥의 조각은 인간 삶의 목적을 의미하는 ‘상칸파라닝 두만디’(삶의 기원과목적), 조화, 번영과 평화를 묘사한다. 특히 게뵥의 조화는 자연과 조화를 이루는 삶의 중요성을 의미한다. 게뵥은 엄선된 재료와 전문가의 기술을 필요로 하기 때문에 이를 갖춘 집은 평범한집이 아니라 특정한 목적을 위해 만들어진 집이라 할 수 있다. 또 다른 방식인 게덱은 일종의 대나무 짜임벽으로 주택의 벽, 벽 마감, 천장 등에 흔히 사용된다. 게덱의 디자인을 활용해 가방이나 샌들, 모자를 만들기도 한다. 흥미롭고 개성 넘치는 디자인을 지닌 게덱은 대나무를 엮는 기술과 집중력이 필요하다. 이 또한 지속가능한 건축 재료라고 생각한다.

박: 보토 주택 내부로 들어가면 가장 먼저 1층의 넓은 현관을 마주하게 된다. 한국 주택에서는 이러한 공간을

주차장용도 외에는 거의 볼 수 없다. 어떤 용도의 공간인가? 이곳과

연결된 1층의 여러 실들은 외부 공간과 어떤 관계가 있는지 궁금하다.

라흐만: 현관의 야외 공간은 건축주가 100명 이상의 사람들이 모여 정기적으로 코란을 낭독하는 공간이 필요하다고 해서 만든 것이다. 공용 실과 차고 역할도 겸하며 공용 실과 연결된 창고에 낭독에 필요한 장비들을 수납한다. 가정부들이 쉴 수 있도록 뒷마당 쪽으로 창을 낸 가정부 전용 실들이 있다. 1층의 주방은 공용실, 가정부 전용실과 하나의 영역으로 연결된다. 인도네시아 인구의 대부분이 무슬림이라 집 안에 기도실은 필수적이다. 이 주택에서는 단순한 기도실 외에도 대중교육 목적을 겸하기 때문에 굉장히 중요한 공간이라 할 수 있다.

박: 코로나바이러스감염증-19 시대에 대응하기 위한 다양한 방식의 공간들이 세계적으로 만들어지고 있고, 특히 주택에서는 공용공간과 거주자들 사이에 커뮤니티의 중요성이 대두되고 있다. 보토주택 평면을 보면 게덱이 설치된 2층 외부에 비어 있는 공간이 보인다. 이러한 곳들은 오히려 지금 시대를 반영하는 반외부 공간으로 보인다. 인도네시아, 특히 자바 지역의 전통가옥의 공간에서 영감을 받았다고 했는데 전통가옥의 평면적 특성을 수직적으로 배치한 이유는 무엇인가?

라흐만: 2층에는 손님맞이를 위한 반외부 테라스가 있는데, 손님들은 이곳을 통해서만 집으로 들어갈 수 있다. 팬데믹 상황과 뉴노멀 시대에 매우 적절한 공간이라고 할 수 있다. 가족실, 부엌, 일하는 공간, 기도실과 같은 덜 사적인 영역은 2층에, 침실 같은 사적인 공간은 3층에 배치했다. 평면구성에서 보토 주택은 개방된 공용 응접실인 펜도포(pendopo), 공적 공간과 사적 공간 사이의 전이 공간인 프링지탄(pringgitan),사적인 휴게실인 오마 달렘(omah dalem)과 같은 전통가옥의 공간 위계에서 영감을 받아 디자인했다. 제한된 부지 안에서 복잡한 요구에 맞춰 공간적 타이폴로지의 위계를 그대로 유지하기 위해 이를 수평적인 것에서 수직적인 것으로 치환한 것이다

박: 이 집의 주된 내용은 단연 ‘수공예'라는 생각이 든다. 집 곳곳에서 다양한 방식의 벽돌 조적과 타일패턴 등과 같이 지역색과 장인정신이 드러난다. 어떤 공간에 어떤 재료를 사용할지를 결정한 과정이 궁금하다. 각각의 구축 방식은 무엇에 착안을 했고, 어떤 발전 과정을 거쳤나?

라흐만: 우리가 보토 주택에서 보여주고 싶었던 또다른 주제는 방금 말한 수공예의 장인정신과 벽돌이라는 재료 자체였다. 우리는 우리의 프로젝트와 사무소가 위치한 자바 동부 지역에서 14세기 마자파 힛(Majapahit) 시대부터 사용되어온 전통적인 조적 건축을 보전하려 했다. 자바 동부의 벽돌 품질은 이미 세계적으로도 잘 알려져 있다. 보토 주택은 마자파 힛 시대에 지어진 사원들과 가까운 곳에 위치하며, 수무르 사원(SumurTemple)과 파리 사원(Pari Temple)은 불과 4km 정도 거 리에 있다. 우리는 이 두 사원의 조적 방식에 대해 연구했다. 그러면서 열세 가지의 새로운 조적 방식을 고안했고 보토주택에 이를 적용하고 싶다는 우리 의견에 건축주도 동의했다. 주택에 사용된 장식은 벽돌, 나무, 엮은 대나무, 시멘트 타일과 같이 모두 전통적인 재료들을 이용해 만들어졌다. 우리는 궁극적으로 현대에 이르러서 점차 사라져가고 있는 수공예가들의 장인정신을 다시금 끌어올리고 지역 장인들의 명맥이 유지되도록 돕고자 했다.

박: 설계사무소는 기술장인들과 어떤 관계를 맺고 있나? 수공예적 디테일을 통해서 전달하고 싶은 메시지는 무엇인가?

라흐만: 우리는 건축가의 전문성이 장인들보다 더 뛰어나다고는 생각하지 않는다. 그래서 장인들과 파트너십을 구축하고 서로에게 유익이 있도록 협업한다. 건축가들은 기술적인 부분과 이를 현장에서 어떻게 적용할지 장인에게서 배우며, 장인들 또한 경험해보지 못했던 디자인 방식을 우리를 통해 접할 기회를 갖는다. 이러한 협력적인 관계는 서로를 평등하게 존중하는 누산타라인들의 사고방식에서 기인한다.

박: 사무소의 다른 주택 프로젝트에서도 이러한 특성들이 보인다. 프로젝트마다 해당 지 역의 숙련공들과 협업하나? 그들과 어떤 방식으로 관계를 맺는지 궁금하다.

라흐만: 보토주택은 우리가 섭외한장인과 건축주 쪽에서 섭외한 장인들이 함께 작업한 결과물이다. 건축주쪽의 장인들은 구조적인 부분들을, 우리 쪽의 장인들은 건축 디자인적 부분과 재료의 디테일한 적용을 담당했다. 이 프로젝트에서뿐만 아니라, 자바동부 이외의 지역에서도 그 지역의 장인들과 협업한다. 우리의 비전은 지속가능한 건축으로서 장인들이 꾸준히 존경받을 수 있게 전통적인 수공예에 대한 지식을 육성하고 현지 재료를 탐구하는 것이다. 이러한 논리를 위해서는 공사 기간 동안 발생하는 에너지와 비용을 최소화할 수 있도록 프로젝트가 진행되는 지역에 따라 장인이라는 인적 자원과 현지 재료라는 물적 자원이 뒷받침되어야 한다.

박: 궁극적으로 당신이 주거 건축을 통해 말하고 싶은 바는 무엇인가?

라흐만: 우리는 선조들이 구축한 누산타라 건축의 정신을 이어받아, 프로젝트마다 각지역의 특성과 문화적 뿌리에서 추출한 각기 다른 성격을 적용했다. 인도네시아는 사방(Sabang)에서 머라우케(Merauke)까지 수백 가지 유형의 전통가옥을 아우르는 풍부한 건축유산을 가지고 있다. 보토 주택은 재료사용, 문화적 특성, 기후에 대응하는 지역 맥락을 고려하여 설계되었고, 이러한 특이점들이 다양성을 발현시켜 여느 건축물들과는 다른 모습을 가지게 했다. 이러한 ‘다양성의 건축’이야말로 누산타라 건축의 핵심이다.

Andyrahman Architect_ Andy Rahman Aprillianto

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN NUSANTARA ARCHITECTURE AND CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE

Andy Rahman Aprillianto graduated from

Institut Teknologi Sepuluh November Surabaya (ITS). After graduation, he, and

Abdi Manaffounded Andyrahman Architect in 2006 and has long been influential

upon the Indonesian architecture community. He is actively participating in

various architectural events and exhibitions, such as the Indonesian

Architecture Public Exhibition in Japan and the Netherlands, and Omah Boto,

which he designed, was selected as one of the 50 Best Architectural Projects

and The 50 Best Houses of 2019 by Archdaily.

Of young Indonesian architects, Andyrahman

Architect has long been interested in the cultural identity of his country and

sought opportunities to develop his understanding through his practice. Andy

Rahman Aprillianto, the principal of Andyrahman Architect, is an architect who

has modernized and expanded Nusantara architecture, a medieval design culture

that flourished in the Indonesian climate. I would like to hear the story of

how such interest came to be demonstrated in an architectural sense.

Park Changhyun (Park): Southeast Asian

architects have begun to speak with greater urgency about locality and

originality in response to globalization. What, do you think, is the foremost

focus of young Indonesian architects?

Andy Rahman Aprillianto (Rahman): Before 2000, Indonesia experienced a crisis where we lost our own architectural identity. However, with the passing of the last decade, the younger generation of Indonesian architects has begun to try to realize the importance of architecture that has an identity, by exploring and developing the local architecture of our own nation. This awareness begins with the understanding that Indonesia is a nation that has a distinctive architectural history equivalent to that found in western architecture, Nusantara architecture. This awareness is what prompts us to continue exploring the legacy of Nusantara architecture to be able to address present and future problems.

Park: What is Nusantara architecture? And how have young Indonesian architects accepted and developed Nusantara architecture in their own ways?

Rahman: We study history from the understanding that Asian people have strong historical and philosophical roots in terms of their culture and architecture, one that is very different from the West, especially Europe and America, and asserting that we possess a different architectural genealogy to them. Based on the statement made by Josef Prijotomo in 2002, 'Nusantara architecture is architecture as a knowledge based on and derived from philosophy, science and architectural knowledge'. He also stated that Nusantara architecture is not traditional architecture'2, it exists in the realm of architectural knowledge (architectural systems and development) while traditional architecture refers to cultural knowledge (anthropology and ethnology). Nusantara architecture is a system of cooperation: not only formed of buildings but also of environmental and societal concerns.'3 Nusantara architecture has an architectural character that responds to a climate characterized by two seasons in Indonesia, evidenced by the application of one technical concept in the form of a breathing wall (a wall that is able to create a good circulation system in a room). In terms of identity, they continue to apply the strong DNA of Nusantara architecture, but the designs and visuals are sensitive to our contemporary context.

Park: Even for young Korean architects, the process of linking Korean characteristics or traditional architectural style to individual designs is not easy. What prompted your interest in Nusantara architecture?

Rahman: As a graduate I majored in architecture at institute Teknologi Sepuluh November Surabaya. After I graduated in 2004, I began practicing architecture in Surabaya and now in Sidoarjo, a city located south of Surabaya with a population of two million. My education at the university greatly influenced my thinking, ways of learning and problem-solving process, especially thanks to one of the professors, Josef Prijotomo, who focuses on the development of Nusantara architecture. He is also committed to supporting the knowledge base related to contemporary Nusantara architecture.

Park: What is Surabaya different from Jakarta, the capital of your country?

Rahman: In my opinion, there are some unique everyday things in the city of Surabaya, such as the typical Javanese language of Arek Suroboyo, and a very popular social culture, namely Cangkrukan-the culture of hanging out with friends, relatives, or anyone through random conversation topics regardless of standing or shared experiences. In this city, it is much easier to greet each other, and we are encouraged to broaden our sphere of acquaintance and connections compared to that in a city like Jakarta, with its larger population and boundaries to socializing with other people.

Park: The part that teaches modernization of Nusantara architecture at the University of Architecture in Indonesia has much to suggest to Korea. In fact, I think the modernization of traditional Nusantara architecture is one of the influences of globalization along with technological development. As architecture of other countries is easily accessible in most Asian countries, I feel that the 'integration of architecture' is accelerating around the world, which replicates each other. As a result, Asian countries are bound to be interested in their own identity. In this context, what is the latest issue that is architecturally agonizing with the development of Nusantara?

Rahman: The general tendency of Indonesian architectural styles is almost the same as architecture in other Asian countries, where most houses adopt distinct modem architectural styles. However, in recent years the development of home design has begun to change, returning to regional values of the material, culture and history that exist in each of these countries. Indonesian architecture has also begun to lead to architecture of a local Indonesian identity. This is in accordance with the vision of our architectural studio to develop contemporary Nusantara architecture. In architectural practice, we work with architectural craftmanship in which through the design and construction process we create mutually beneficial cooperation between us as a team of architects and craftsmen as executors in the field. That is what makes us aware of the importance of Nusantara architecture as a worthy architectural form on our terrain, Indonesia. This identity ultimately expresses the spiritual conviction, 'Architecture as a Way to Return to the Path of God’.

Park: We would like to know more about the

background to Omah Boto. What did you discuss with the client when embarking

upon the project?

Rahman: The client of Omah Boto is a construction entrepreneur in Sidoarjo. Before hiring us, he had studied many architects in Indonesia, and finally selected me as the architect to design his house. We happen to live in the same city, Sidoarjo. At that time, the client wanted to renovate his house using bricks as the primary material. He had high expectations that the brick material would be exposed, because he had admired our projects in East Java that use bricks. During the design discussion process, the owner expressed a desire to present Indonesian architecture through modem and contemporary designs. Based on these discussions, we know that he is driven by the same passion as our own to explore and develop architectural designs that represent the character of Indonesian architecture, but through a modem and contemporary perspective. Therefore, every single person who visits this house tends to assume that it is a typical Indonesian house.

Park: What makes the impression left by this house distinct is its brick façade. Is this porous façade, composed of bricks that are laid at given distances, common in Indonesia? It looks like it has been the result of contemplating climate conditions as well as the structures relationships with its neighbors. What did you consider on light and ventilation?

Rahman: We took a simple box design to represent the shape of a brick. Bricks are used as the cells and DNA in Omah Boto. In addition, we took the principle of a breathing wall from the many examples in traditional houses of Indonesia, namely the Gedek (a woven bamboo wall). Gedekfunctions to maintain privacy of activities taking place in the house and to circulate air and sunlight so that the room is not hot and humid. We applied Gedekto Omah Boto's skin. The difference is that we didn't use woven bamboo, but woven bricks. This is what makes Omah Boto look 'extraordinary' in comparison to the neighboring houses of classical and Mediterranean architectural styles. Omah Boto could be thought to criticize its surrounding context, while also built in answer to local climate conditions and the cultural context.

Park: Could you please introduce Gedekin more detail? How is it made and how was it applied to traditional houses? Are there any other traditional methods or materials besides Gedek?

Rahman: Apart from the knowledge of brick tectonics, Omah Boto also has other elements familiar to the homes of many Indonesians, especially the Javanese, namely Gebyok and Gedek. Gebyokis a typical piece of Javanese furniture in the form of a room partition which generally features Javanese carvings and is made of high-quality teak wood. The history of Gebyok can be traced back to the life of Queen Kalinyamat, the third king of the sixteenth-century Demak Sultanate. During the reign of Queen Kalinyamat, the Gebyok was invented and was swiftly understood as a masterpiece with its intricate and beautiful carvings. Gebyok reflects aesthetic and ethical thoughts and feelings. The carvings on the Gebyokdescribe the purpose of human life, Sangkan Paraning Dumadi (origin and purpose of life), harmony, prosperity, and peace. The harmony of the design of theGebyok reveals the importance of living in harmony with nature. A house that uses a Gebyok may not be an ordinary house but a preferred house, because to create a Gebyok requires selected wood and the best experts of its time. Gedek is a woven bamboo technique commonly used in house walls, wall coverings, and ceilings, and throughout its evolution Gedekalso also been used to make many things from bags, sandals, to caps. Making works from Gedek requires skill and concentration to weave bamboo into interesting and unique motifs. The presence of the Gedek is that of a sustainable building material.

Park: Upon entering Omah Boto, one first faces a wide porch on the first floor. In Korean homes, these spaces are rarely seen except for if used as parking lots. What kind of space is this and what is its purpose? How are the various threads that run throughout the first floor to lead to this space connected to the spaces outside?

Rahman: The first floor at Omah Boto functions as a garage and communal room that accommodates the client's needs, such as routine recitation activities with a capacity of more than 100 people. Then there is a warehouse as a storage area for recitation equipment connected to the communal room, and a housemaid's room that has a window facing the back garden, to make this space as comfortable as possible. The kitchen on the first floor is connected to a common room and a private room for the housemaid. Prayer rooms are essential at home because most of Indonesia's population is Muslim. In addition to the simple prayer room, this house is a very important space because it serves both public educational purposes. On the second floor there is a semi-outdoor terrace for guests, where guests can only reach their spaces through this area. Therefore, it is very well suited to the demands of the 'new normal' in the age of the Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19). The second floor also contains semi-private rooms such as the family room, a dining room, a work room, and a prayer room. The third floor contains private rooms, such as the master bedroom and several other bedrooms. In the plan composition, Omah Boto developed from the established hierarchy of a traditional Javanese house layout, namely the pendopo room (public space for receiving guests, communal spaces), pringgitan (transitional room between public and private spaces) and omah dalem (private space for resting). The need for complex spaces and the restrictions incurred by the size of the site resulted in a spatial typology that runs from horizontal to vertical, but hierarchically remains the same.

Park: I think the main content point of this house is ‘handicraft’. Local colors and craftsmanship are revealed throughout the house, such as various types of brick masonry and tile patterning. I'm curious about your decision process when deciding which materials to use in which space: what was the idea behind each implementation and how were they developed?

Rahman: Another theme that we want to explore at Omah Boto is the artisan spirit of handicraft and the nature of the materials, here primarily the bricks. We tried to preserve the existing tradition of brick architecture in East Java, a method cultivated since the fourteenth century Majapahit era in the eastern Java region, where our projects and studios are located. The bricks in East Java are known worldwide for their high quality. Omah Boto is located close to temples built during the Majapahit era and Sumur Temple and Pari Temple are only about 4km away. We studied the method of steering the two temples. In the meantime, we came up with 13 new methods of manufacture, and the architect agreed with our suggestion that they should have applied them to the Omah Boto project. The ornaments used from Omah Boto are traditional materials, bricks, wood, woven bamboo, and cement tiles. We wanted to lift the spirit of craftmanship and to support local material craftsmen survive at a time in which their industry is increasingly fading from view.

Park: How does the design office communicate with the technology craftsmen? And what message do you hope to convey through these handcrafted details?

Rahman: Professionally speaking, we don't think the expertise of architects is better than craftsmen. Therefore, we build partnerships with artisans and collaborate to benefit each other. All we as a team of architects can do is learn about technical things and how to solve them in the field. Likewise, through us craftsmen can learn the means and methods of design never experienced. This cooperative relationship stems from the mindset of the Nusantar people which focuses on mutual respect.

Park: These characteristics are also witnessed in other housing projects displayed in your office. Do you collaborate with local skilled workers for each project? I wonder how they relate to each other.

Rahman: Omah Boto is the result of the collaboration between the craftsmen from us and the client. Architectural craftsmen were responsible for structural parts, and our craftsmen were responsible for architectural design and detailed application of materials. In addition to this project, we collaborate with local craftsmen outside of East Java. Our vision is to foster knowledge of traditional handicrafts and explore local materials so that craftsmen can be constantly respected as sustainable architecture. This logic requires the support of human resources as craftsmen and physical resources as local materials, depending on the region where the project is being carried out to minimize energy and costs generated during the construction period.

Park: Ultimately, what would you like to say through your residential architecture?

Rahman: We inherited the spirit of Nusantara architecture built by our ancestors and applied the characteristics of each region and elements extracted from cultural roots in each project. Indonesia has a rich architectural heritage spanning hundreds of traditional houses, from Sabangto the region of Merauke. Omah Boto was designed to consider the local context of material use, cultural characteristics, and climate, and these peculiarities expressed diversity, giving it a different unique disposition to that of other buildings. This 'diverse building' is now at the heart of Nusantara architecture.