스몰프로젝츠_ 케빈 마크로우

예술과 자본의 경계에서

케빈마크로우는 1988년미국오레곤대학교에서 건축학과를 졸업하고, 1991년 매사추세츠 공과대학교에서 석사 학위를 받았다. 2002년

말레이시아를 기반으로 스몰프로젝츠를 설립하여 말레이시아, 태국 등에서 활동 중이다 건물설계 뿐만 아니라

글, 조각, 강연 등을 동해 건축 작업을 이어가고 있다

케빈 마크 로우(로우): 건축에서 컨텍스트는 기본적으로 대지의 지형적 특성, 대지에 적용되는 여러 법규 사항, 인근건물과 주변상황 등을 의미한다. 나는 프로젝트를 시작할 때 주어진 대지에서 일어나는 사람들의 활동을 관찰하고 여러 활동과 관련된 구체적인, 유형(有形)의 컨텍스트를 조사하는 리서치를 진행한다. 유형의 결과물이나 물리적 표현을 하기에 앞서 최대한 냉정하고 비판적으로 주어진 조건과 상황을 파악하려고 한다. 그리고 대지의 고유한 문제나 이슈 등 무형(無形)의 컨텍스트를 이해하는 단계를 진행한다. 구체적이고 또 추상적인, 다시 말해 유형적이고 또 무형적인 컨텍스트 모두에 질문을 던지고 또 답하며 둘사이의 균형을 잡으려고 한다.

로우: 내가 하는 일은 개인적인 것과 그렇지 않는 것 사이의 균형을 잡는 것 보다는, 이미 구체적인 컨텍스트를 갖고 있는 프로젝트의 고유한 관계를 향해 적절한 질문을 던지는 것에 가깝다. 방향을 설정하고 질문을 던진 이후에는 프로젝트마다의 고유한 이슈, 문제에 대응하는 해결 방법에 따라 모든 사항들을 결정한다. 균형은 작업하면서 자연스럽게 얻어진다.

박: ‘코멘터리’ 카테고리에서 ‘콘크리트’ 에세이도 재미있게 읽었다. '‘인류에 여러 인종이 있듯이, 콘크리트는 누가 붓느냐에 따라 뚜렷하게

구분되며 상이하다”는 말에 크게 공감했다. 콘크리트는 나라마다

그 결과물이 다르게 나타나고, 또 건축가마다 사용하는 방식도 다양하다.

당신이 주목하는 콘크리트의 특징과 장점은 무엇인가?

로우: 거의 20년 전에 콘크리트에 대한 글을 썼다. 나라마다 다른 혼합비율, 거푸집이라는 유전적코드 등에 따라 형태가 결정되는 콘크리트의 본성에 대해 썼다. 여기에 주목한 이유는, 건축가가 강박적으로 노력하지 않고도 건축 작업에서 개성을 찾을 수 있는 가장 쉬운 방법 중하나가 될 수 있다고 생각했기 때문이다. 현장에서 타설될 때마다 야기되는 콘크리트의 불완전성은 컨텍스트가 동일한상황에서도 엄청난 다양성을 유발한다. 이러한 콘크리트의 본성 덕분에 아주 급진적인 노력이 없더라도 다양성을 창출할 수 있다. 거푸집을 구성하는 방식, 주조비율과 제조방식 등에 있어서 공정에 작은 변화만 주더라도 다른 결과물을 낼 수 있는 것이다.

로우: 말레이시아에서 규모에 상관없이 거의 모든 프로젝트에서 가장 가성비가 좋은 재료가 철근콘크리트다. 이러한 재료선택이, 큰 가치에의 필요성보다는 경제성에 의해 결정되어 걱정되는 부분도 있다. 나는 콘크리트를 좀더 인간적으로 사용하려고 할 뿐이다. 마감재료, 구조적 기능의 필수적인 부분으로 사용하려고 한다.

로우: 나에게 디테일은 사물과 아이디어가 만나는 친밀하고 필수적인 결합이다. 나는 도시의 건물들 간의 관계가, 하나의 건물이 기존의 컨텍스트에서 두드러지게 표현되는 것보다도 더 중요하다고 생각하는데, 디테일도 다르지 않다. 디테일은 사물과 아이디어 사이의 보다 심오한 관계를 해결하고 발전시키기 위해 존재한다. 디테일이 유일하게 단점을 가질 때에는 그 자체의 아름다움만을 위해 존재하는 경우다. 그 외의 모든 다른 측면에서 장점을 가질 수 있다. 기후와 배수, 배수와 건물, 건물과 방, 방과 화장실, 화장실과 문, 문과 손잡이, 손잡이와 손등 여러 요소들 또는 여러 아이디어들의 관계의 맥락적 흐름은 모든 디테일에서 가장 중요하다. 그리고 이 모든 관계들이 잘 지켜질 때, 가장 정제된 아름다움을 표현할 수 있다고 생각한다. 디테일을 아름답게만 표현하려는 노력은 건축가가 추구할 수 있는 가장 불필요하고 퇴행적인 감성이다. 아쉽게도, 많은 건축가들이 이런 감성에 쉽게 빠지곤 한다.

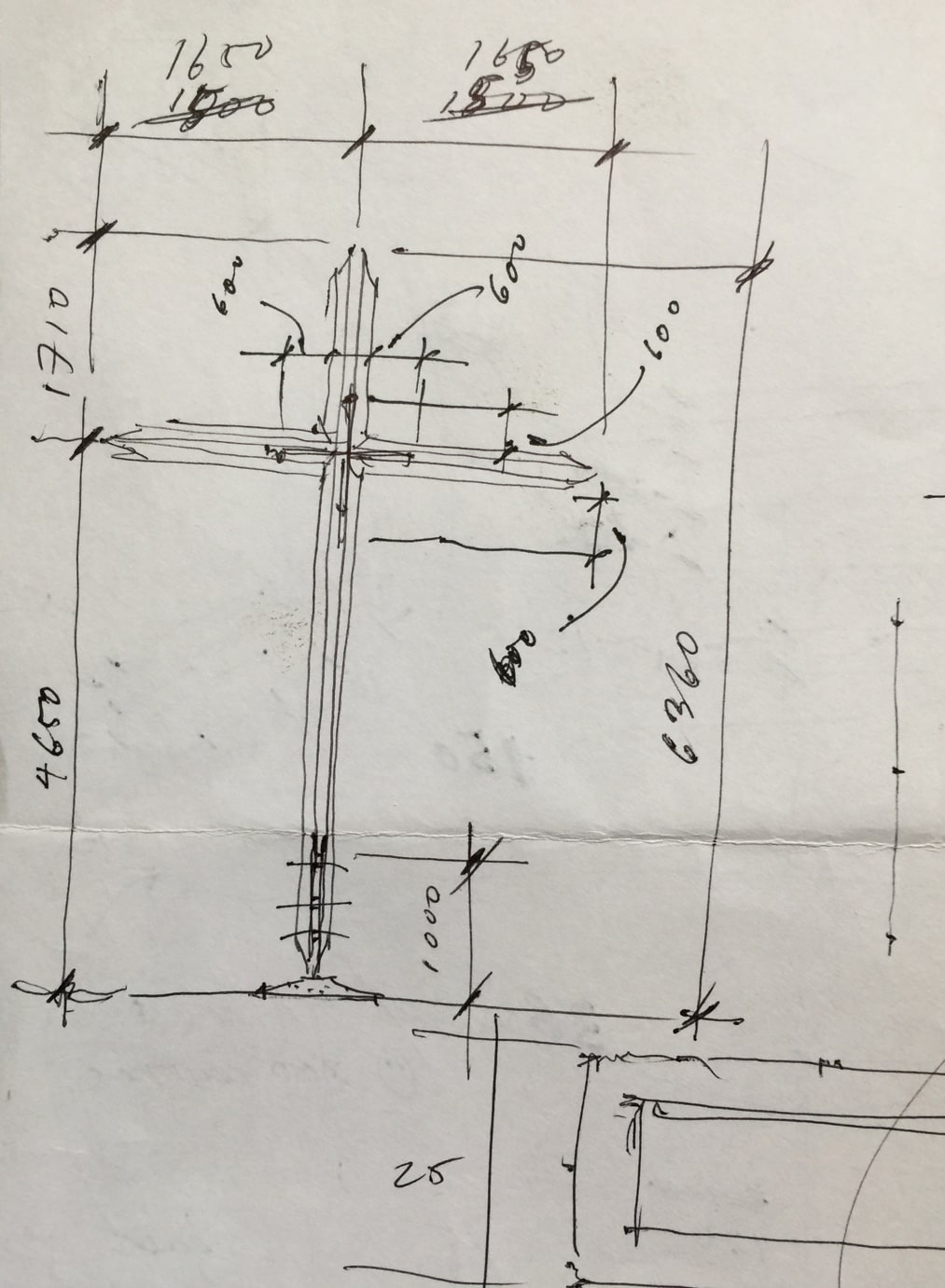

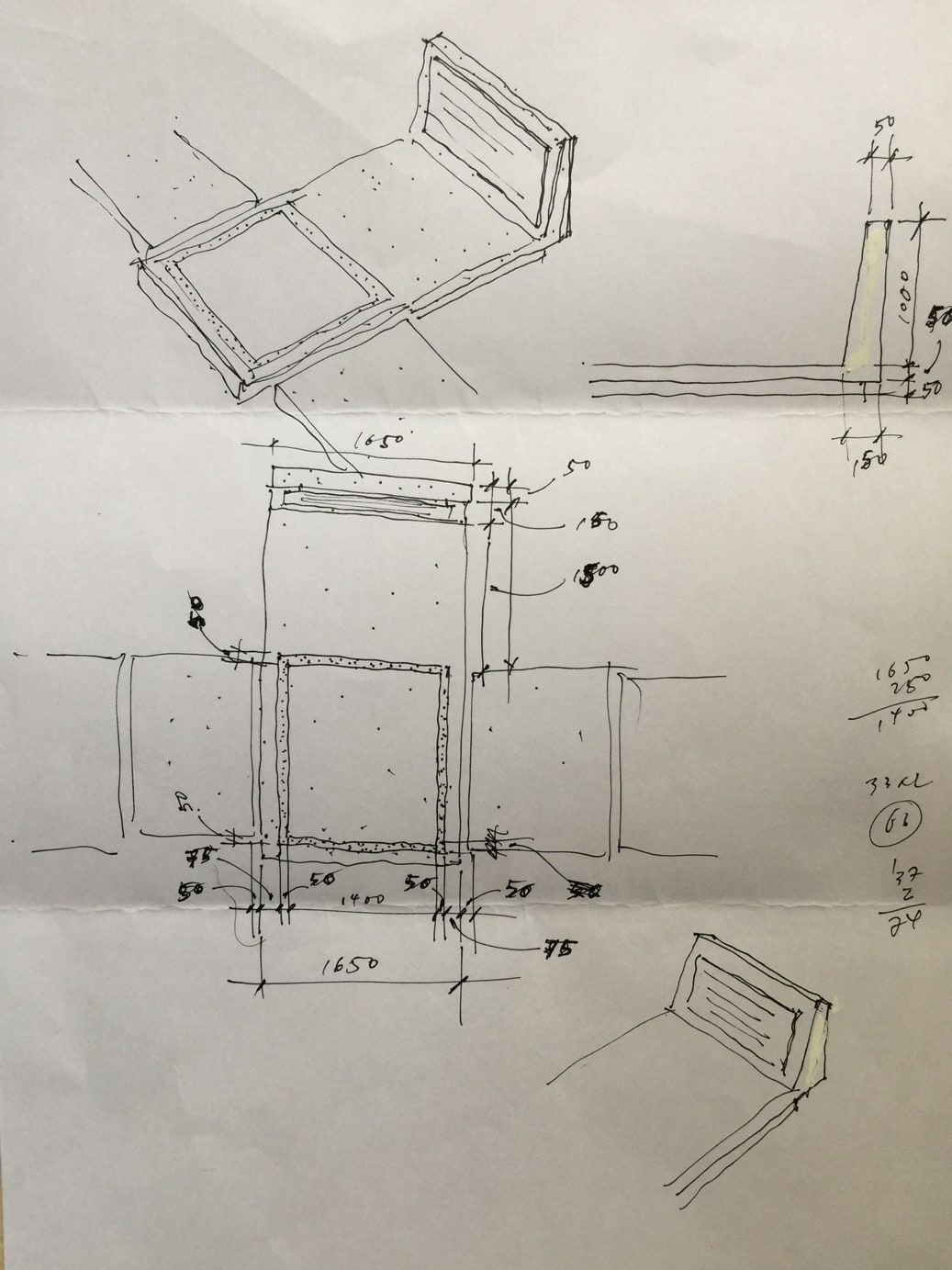

로우: 지리적으로 접근이 쉽지 않은 곳에 위치하다 보니 재료 수급에 제약이 컸다. 비포장도로로 운반할 수 있는 시멘트, 모래, 철근만 사용하기로 결심했고, 투입되는 재료의 양 자체도 절약해야 했다. 지붕을 가장 경제적인 형태인 사각형으로 만들고, 모든 수직 부재를 10mm 철근을 세우는 것으로 해결했다. 벽 시공에도 비용이 많이 들었는데, 벽 자체가 예배당에 꼭 필요한 요소는 아니라 생략했다. 철근을 이용한 구조물이 충분한 전단력을 확보할 수 있도록 중앙 공간은 원형으로 계획했고, 3~4명 단위의 소규모 모임을 위해 모서리를 열린 공간으로 만들었다.

로우: 마을 중심부에 있는 지역 교회는 최소한의 콘크리트 기둥과 보를 구조로 하고, 거칠게 못을 박은 목재와 금속 골판 지붕이 얹어진, 이음새를 만드는 데 전혀 노력을 기울이지 않은 건물이었다. 교회 건물이었지만 학교 행사부터 마을 회의, 심지어는 저장과 보관에 이르기까지 다목적 홀과 다를 바 없는 대접을 받았다. 숭배를 목적으로 한 건축물의 전례가 없었기 때문에 역사적 맥락이 그리 많지 않았다. 내가 발견한 유일한 문화적 혹은 사회적 컨텍스트는 마을의 거의 모든 구성원들이 목재로 자신들의 집을 지었지만, 공공이 함께 사용하는 건물에서는 집에 비해 노력이 부족했다는 사실이다. 농촌지역에서 공동체 의식과 유대감이 더 깊다고 생각했던 것과 반대되는, 꽤나 흥미로운 발견이었다.

로우: 사회가 건축을 이해할 때 피상적인 아름다움만 이야기하곤 한다. 사람들 사이에 맺어질 수 있는 어떤 심오한 관계보다 말이다. 심지어 건축가도 그런 경우가 있다. 이번 프로젝트의 경우에는 바레오 마을의 정착에 대한 건축적 포부, 미학과 무관하지 않은 실용성, 용도, 생존의 문제를 지향하는 것이 아닌가 하는 생각이 든다. 재료 선택은 아침 공기와 같이 흔하고 일상 같았더라도 예배당은 그들에게 미적으로 놀라움을 안겨주었을 것이다.

로우: 품위라는 단어가 이렇게 쓰여도 되는지 모르겠다. (웃음) 공사에 시간이 아주 많이 걸리진 않았다. 공사에 참여한 사람이 적고 자재 배송 지연으로 단지 예상했던 시간보다 오래 걸렸을 뿐이다. 바레오로 가는 도로에 산사태가 일어나서 자재 배송을 기다렸던 어려움은 있었다. 그리고 바레오마을 사람들이 많은 노력을 기울였다. 부활 예배당 부지의 정원을 가꾸기 위해 언덕 꼭대기 전체를 다듬고 식재를 심고 정리했다.

로우: 예배당을 이용하는 커뮤니티가 그런 느낌을 받기를 바란다. 이곳은 매주 36명 정도의 큰 모임과 개인 또는 매우 작은 모임들이 매일 진행된다고 한다. 만약 이 프로젝트가 아주 큰 공동체 교회를 위한 것이었다면 전혀 다른 디자인이 나왔을 것이다.

로우: 프로젝트의 타깃은 부유층으로 다른 사회 구성원보다 프라이버시를 우선시할 것이라 예상했다. 여기에 사교와 교류의 기회가 보편적으로 주어지는 것이 아니라 선택적으로 제공되도록 했다. 예를 들어, 필요에 따라 쉽게 제거할 수 있도록 설계된 벽을 통해 이웃 간의 만남이 이루어진다. 그렇지만 풀장, 에어로빅과 웨이트를 위한 파빌리온, 요가실, 커뮤니티 주방 겸 식사공간, 바비큐를 위한 공유 가든 등 다양한 시설이 있는 옥상에서 이웃끼리의 상호작용이 가장 활발하게 일어날 거다. 지상 1층에도 라운지, 도서관, 넓은 정원과 연결된 공유 공간이 곳곳에 있어서 개인 공간이 아님에도 불구하고 ‘내 집에 왔다’는 느낌이 있을 거라 생각한다.

로우: 환기 문제는 수십 년 동안 논의되어 왔지만, 주로 주거지와 저층건물에 관해서만 논의되었다. 커다란 변화를 불러일으킬 만한, 패러다임을 흔들 만한 큰 변화가 있지는 않았다. 윈드쉘 나라티왓은 몬순기후 지역에 위치한 50층규모의 건물에서 환기 문제를 해결하기 위한 아이디어가 다뤄진 첫 번째 경우라는 점에서 그 의미가 컸다. 어쩔 때는 궂은 날씨에 바람이 심하고, 또 때로는 기후가 정체되는 현상이 예측 불가능하게 찾아오는 곳이었다. 파악해야 할 컨텍스트가 너무나도 많았고, 심지어 그곳에 떨어지는 빛조차 내가 알던 것과는 달랐다. 그랬기에 프로젝트 처음부터 태국 전통 주거 건축이 어떻게 강한 빛, 눈부심, 그림자의 대비를 다뤄왔는지를 살펴봤다. 방콕의 오래된 목조 주택은 내외부공간의 온도, 빛 그림자를 극명하게 대비하고 있었는데, 이는 오늘날 방콕의 스카이라인을 형성하는 전형적인 주거용 고층빌딩에서는 찾아볼 수 없는, 이제는 사라진 문화적 감수성이다. 자연 채광, 바람흐름 등에 대해 새로 경험하고, 배우고 발견하고 실수하고 해결해가는 과정을 겪었다.

로우: 이 프로젝트는 클라이언트가 방콕 살라댕 지역에 있는 고급 펜트하우스보다 더 좋은 집을 찾는 것으로 시작됐다. 그는 전세계 어느 도시에서나 볼 수 있는, 세련되지만 전형적인 커튼 월 펜트하우스를 몹시 싫어했다. 그렇다고 정원이 딸린 단독주택을 짓기 위해 도심지에 막대한 돈을 쓰고 싶지는 않았다. 그래서 클라이언트 자신이 살고 싶은 단독주택을 고층으로 짓는다면 다른 사람들도 좋아할 것이라 생각하며, 자신의 집이 들어설 한 개 층의 공간을 다른 층의 판매 수익으로 충당하고자 했다. 이 프로젝트는 일반적인 2층 규모의 전원 주택이 갖춘 여러 조건들로부터 아이디어를 얻어 진행된 것이기에 ‘상품’처럼 보일 수밖에 없다. 글로벌비즈니스에서 상업적이고 투기적인 측면과 관련하여, 클라이언트와 나의 이해가 일치했기 때문에 이 프로젝트를 진행할 수 있었다. 단지 수익을 내는 데만 초점을 맞추지 않고 다양한방식으로 주거 환경을 개선하기 위해 설계했고 좋은 결과가 나왔다고 생각한다.

로우: 나는 오늘날 우리 사회에서 사회적 매개가 부족한 이유가 건축보다는 사회경제적 문제와 연관된다고 생각한다. 전 세계적으로 지역사회와 사회적 상호작용이 가장 많은 동네는 빈민가와 도시의 빈곤한정착촌이다. 그리고 이러한 동네의 주거시설은 거주자들이 부와 재산을 조금씩 더 축적해가는 과정에 있어서 점차 사라지고 ‘보호'된다. 주거시설이 근본적으로 공유공간과 사적 공간사이의 균형이라는 사실은 종종 잊혀진다. 그러나 부가 일정한 임계점을 넘어서면, 공유 공간과 사적 공간의 균형을 맞추려는 인간의 욕구에서 벗어나 축적된 부를 보호하는 쪽으로 다시 한번 근본적인 변화를 겪는다. 이는 부유한동네에서 커뮤니티 시설, 공유공간이 점점 부족해지는 현실과 관련 있다. 건축이 상품화되거나 비판적 형태를 가지는 순간은 앞선 일들이 모두발생한 이후로, 그 시점에는 사회경제적 편견에 반응하는 것밖에 할 수 있는 게 없다. 하지만 빈민가와 불법 거주자정착지에서는 그렇게 큰문제가 되지 않는다. 그곳의 구성원들이 ‘사적’이고 ‘방어 가능한' 공간을 누릴 만큼 충분히 부가 축적되면 치안이 좋은 중상위층동네로 이동하기 때문에 빈민가, 불법 거주자정착지는 특정수준을 넘어서는 큰 변화가 없다. 하지만 사람들의 소득과 사회적 지위는 점진적으로 그리고 지속적으로 높아질 것이기에, 이웃 간의 교류와 상호작용이 전체적으로 점점 더 옅어지는건 아닐까 하는 걱정이 든다.

SMALL PROJECTS_ Kevin Mark Low

ON THE BORDER BETWEEN ART AND CAPITAL

Kevin Mark Low received his

BArch in University of Oregon in 1988 and M. S. Arch in MIT in 1991. He

established small projects in 2002 based in Malaysia and has worked various

projects in Malaysia, Thailand, and other countries. He has been professionally

involved in writing, environmental sculpture, illustrating, teaching, and

copyrighting.

Kevin Mark Low (Low): Architectural context is, at a fundamental level, a site's geographical properties, the regulations it abides by, the neighboring buildings, and the surrounding environment, to name a few. I always begin research of a specific context by observing the people and the tangible activities and relationships in and around any specific site. I attempt to study them as critically and thoroughly as possible before attempting to understand the tangible outcomes or physical expression of these contextual relationships in the built form. I then try to understand the problems or issues that are unique to that context. I proceed by forming a constant dialogue between questions and answers concerning the specific and the abstract, the tangible and the intangible, to hold any understanding between the two aspects of a context in tension.

Park: How do you balance the many kinds of

context understood in architecture; background, design preferences, among

others? Are there instances in which your personal context takes precedent over

a project context?

Low: My responsibility is less towards balance than towards discovering relevant questions that address the unique relationships which already characterize a specific context. All my decisions thereafter are guided by the relevance my solution has when answering the issues or problems specific to the context of the project. One naturally arrives at balance when discovering and working with the appropriate questions.

Low: I wrote almost twenty years ago about the nature of concrete as born from the genetic code of its formwork and its unique mix from country to country. I believe it to be one of the easiest ways of locating personality in a particular work of architecture. The imperfections of poured concrete from one project to another already provides tremendous variety in character, even within the same specific context. These characteristics provide diversity within the project without any excessive effort. Just a small change in the process, to the formwork or sand mix, can create varied results.

Low: For almost all projects in Malaysia, regardless of scale, reinforced concrete is the most cost-effective material to use. I am afraid my choices have been determined more by economy than a deeper consideration of critical worth. I try to use concrete in a more humanizing fashion, as a material of finish or an integral part of its structural function.

Low: Details for me are simply the intimate and vital junctions where things and ideas meet. I argue that the relationships between buildings in any city are more important than a statement made by a single building in speaking louder than its pre-existing context: details are no different. They exist to resolve and develop more profound relationships between things and ideas. A detail has failed only if it exists for its own aesthetic impression and nothing more. A detail is an advantage in every other way because it provides a contextual flow of relationships, be it between climate and drainage, drainage, and the building, building and room, room and toilet, toilet and door, door and handle, or handle to hand. And, when all these relationships are attended to well, the detail will simply express the beauty of the relationships it had considered. The effort put into making a detail look beautiful in and of itself is the most unnecessary and regressive sensibility any architect can pursue. Unfortunately, it is also a very common pursuit in the profession.

Park: I'm curious how these themes have

been applied in your projects. What was the context behind the Chapel Project

(2019), located in the middle of a mountain in Bareo, Sarawak in Malaysia?

Low: Almost everything revolved around budgeting for the quantity of material used due to these difficult geographical conditions. We opted only for materials transportable via the dirt road, cement, sand, and reinforced bar, while also minimizing the quantities of the materials themselves. The roof would be made to fit an economical orthogonal square, and all vertical support members would be built with 10mm reinforced bars. Since walls cut into our spiraling expenses and were deemed unnecessary in the chapel, they were omitted. The central gathering space was inscribed as a circle to develop better lateral support for the structure and the corners were left open for a gathering of smaller groups of three to four people.

Low: The community church in their town center was constructed very economically with minimal concrete columns and beams, a roof of crudely y bolted and nailed timber, and walls of metal siding, with little to no effort at all put into the crafting of the joints. As a rural settlement, the structure was treated no differently from a multi-purpose hall to serve anything from a school event to a town meeting or perhaps even for use as general storage. Not having much of a precedent for their purposes of dedicated worship, there was not much of historical context to draw from. The only sense of cultural or social context I discovered came from the fact that almost every member of the community built their own residences out of timber, but all their shared community structures lacked the same pride of effort as their own personal dwellings. It was an odd discovery because one would want to believe that rural settlements have a deeper sense of community.

Low: Society, including architects, largely only understands architecture in relation to superficial beauty, rather than to the more profound relationships that can be forged between people. In the case of the architecture aspirations regarding the settlement of Bareo, I suspect that these are more directed at issues of practicality, use, and survival, rather than anything having to do with architectural ambitions or aesthetic potential. Although the choice of materials is as common and 'everyday' to them as their morning mountain air, perhaps the chapel was an aesthetic surprise.

Low: I am not sure if dignity is the right word! (laugh) The construction was not actually time-consuming. It only took longer than it could have because of the limited number of people involved in its construction and the delays in material delivery. There certainly were difficulties in waiting for delivery of the materials because of the landslide damage to the main trunk road to Bareo. Although, the people of Bareo provided a lot of assistance. They planted, trimmed, and cleared the entire hilltop garden to the simple landscape plan I developed for the project.

Low: I hope this is how the community feels when using the chapel. From what I have heard, it is used each week by larger gatherings of about 36, and by individuals or very small groups every day. It would have been a different design if the project had been for a full community church.

Low: It was felt that the target market of the project, the wealthy, would prioritize privacy over all else, for which opportunities for sociability were provided as options rather than standards. For instance, opportunities for socializing have been created by way of walls that have been designed to be easily removed if so desired. However, the greatest degree of interaction between the neighbors would be on the rooftop where the shared facilities of a lap pool, the aerobics and weights pavilion, a yoga room, a community kitchen/dining area, and a community garden for barbeques are located. The ground level also features what is called a shared living room, a large space with a library and multiple lounges that open to the ample garden, such that the arrival home need not have to be only upon entry into one's own upper floor.

Low: The issues of cross ventilation have been discussed multiple times across the decades, but primarily in relation to residences and low-rise typology and not always in terms of the greater effect and ultimate changes to dominant paradigms. What was different and vital for the Windshell Naradhiwas was that it would be first time such ideas would be addressed in a fifty-story tower in the monsoon tropics, with extreme wind loads during inclement weather and very still air during certain times of the day in the unpredictable transition months. There were so many contextual unknowns to deal with, but the quality of light was not one of them. I had known that the dwellings would be configured as a return to the traditional Thai home, particularly in relation to the strong sun rays and the glare of a typical Bangkok day. The cultural sensibilities of internal coolness, light, and deep shadows in the old timber houses were nowhere to be found in the typical residential high rises of Bangkok. It was an experience of learning anew, discovery, and considering the typical mistakes when designing to contend with natural elements such as light and wind.

Low: The project took shape as the client was absorbed in looking for a better place to live than his current upmarket penthouse in the Saladaeng neighborhood. He disliked the fashionable but typical glass curtain-walled penthouses found all over metropolitan centers of iconic global cities intensely but did not wish to spend the stratospheric amounts of money required for downtown land to build a house with a garden. So, he desired to build the sort of high rise dwelling that he knew others would also appreciate, and in doing so, afford an entire floor in the project for his own home from its profits. So, the project was seen to be less of 'product' as such, than an exploration of ideas for everything that could be found in a two-story house with a garden. In relation to the commercial and the speculative aspects of housing development in the global industry, I agreed to be involved in this project because the client aligned with my understanding of the problems in the current paradigm conceiving of a diverse and balanced environment for habitation rather than merely focusing on making profit.

Low: I think the problems regarding the lack of social agency in our communities today is less to do with architecture than with socioeconomics. Neighborhoods globally with the greatest amount of community and social interaction are slums and impoverished urban settlements. Even certain dwellings in these communities become gradually more removed and 'protected' as their occupants accumulate a little more wealth and possessions. It is often forgotten that one of the fundamental needs of any dwelling is the balance between shared and private space. But to surpass a certain threshold of accumulated wealth, the equation again undergoes a fundamental shift, from the human need for good balance of shared to private space, to that of protecting the wealth one has accumulated. This is the root of the issue, regarding the increasing lack of community, neighborliness, civic and shared domains, in any specific residential district. Architecture, either in commodified or critical form, merely responds thereafter to this socio-economic bias. It is not as much of a problem in the slums or squatter settlements, because the moment a member of such a community has accumulated sufficiently to afford more 'private' and 'defensible' space, they move to low/middle class neighborhoods of relatively greater perceived security, leaving the slum relatively unchanged beyond a certain point. But in neighborhoods from low/middle to upper class incomes and social standing, the path to upgrade and ever heightened 'removal' begins its gradual but unstoppable journey thereafter, to less and less neighborhood interaction and connection.

예술과 자본의 경계에서

케빈마크로우는 1988년미국오레곤대학교에서 건축학과를 졸업하고, 1991년 매사추세츠 공과대학교에서 석사 학위를 받았다. 2002년

말레이시아를 기반으로 스몰프로젝츠를 설립하여 말레이시아, 태국 등에서 활동 중이다 건물설계 뿐만 아니라

글, 조각, 강연 등을 동해 건축 작업을 이어가고 있다

이번에 소개할 건축가는 말레이시아의 수도 쿠알라룸푸르에 기반을 두고 있는 스몰프로젝츠다. 스몰프로젝츠의 대표 케빈 마크 로우는 미국 오레곤대학교와 매사추 세츠공과대학교에서 건축과 예술을 공부했고, 말레이시아로 돌아와 GDP아키텍츠에서 11년간 근무한 뒤, 2002년 스몰프로젝츠를 설립했다. 본인의 스튜디오를 개소한 지도 어느덧 20년이 지났지만, 여전히 건축프로젝트 뿐만 아니라 우편함 같은 작은 스케일까지 디자인하고, 꾸준히

건축 이론을 토대로한 에세이를 쓰고 있다. 글과 작업에 녹아 있는 그의 생각을 함께 짚어보자.

박창현(박): 스몰프로젝츠의 웹사이트에는 ‘코멘터리’라는 카테고리가 있다. 건축을 주제로 하는 에세이가 모여 있는데, 그 첫 번째 글이 ‘컨텍스트’를 다룬다. 에세이에서 "존재하는 모든 것은 저마다의 관계들로 촘촘하게 둘러싸여 있는데 그것을 컨텍스트라고 한다” 고 표현한바 있는데, 구체적으로 건축에서 콘덱스트란 무엇인가?

케빈 마크 로우(로우): 건축에서 컨텍스트는 기본적으로 대지의 지형적 특성, 대지에 적용되는 여러 법규 사항, 인근건물과 주변상황 등을 의미한다. 나는 프로젝트를 시작할 때 주어진 대지에서 일어나는 사람들의 활동을 관찰하고 여러 활동과 관련된 구체적인, 유형(有形)의 컨텍스트를 조사하는 리서치를 진행한다. 유형의 결과물이나 물리적 표현을 하기에 앞서 최대한 냉정하고 비판적으로 주어진 조건과 상황을 파악하려고 한다. 그리고 대지의 고유한 문제나 이슈 등 무형(無形)의 컨텍스트를 이해하는 단계를 진행한다. 구체적이고 또 추상적인, 다시 말해 유형적이고 또 무형적인 컨텍스트 모두에 질문을 던지고 또 답하며 둘사이의 균형을 잡으려고 한다.

박: 복잡한 컨텍스트, 저마다의 배경, 디자인 선호도 등 설계에 필요한 여러 요인들 사이에 어떻게 균형을 맞추는가? 의사결정을 함에 있어서 프로젝트와 관련된 컨텍스트보다 당신의 개인적 컨텍스트가 우위에 서는 경우는 없는가?

로우: 내가 하는 일은 개인적인 것과 그렇지 않는 것 사이의 균형을 잡는 것 보다는, 이미 구체적인 컨텍스트를 갖고 있는 프로젝트의 고유한 관계를 향해 적절한 질문을 던지는 것에 가깝다. 방향을 설정하고 질문을 던진 이후에는 프로젝트마다의 고유한 이슈, 문제에 대응하는 해결 방법에 따라 모든 사항들을 결정한다. 균형은 작업하면서 자연스럽게 얻어진다.

박: ‘코멘터리’ 카테고리에서 ‘콘크리트’ 에세이도 재미있게 읽었다. '‘인류에 여러 인종이 있듯이, 콘크리트는 누가 붓느냐에 따라 뚜렷하게

구분되며 상이하다”는 말에 크게 공감했다. 콘크리트는 나라마다

그 결과물이 다르게 나타나고, 또 건축가마다 사용하는 방식도 다양하다.

당신이 주목하는 콘크리트의 특징과 장점은 무엇인가?

로우: 거의 20년 전에 콘크리트에 대한 글을 썼다. 나라마다 다른 혼합비율, 거푸집이라는 유전적코드 등에 따라 형태가 결정되는 콘크리트의 본성에 대해 썼다. 여기에 주목한 이유는, 건축가가 강박적으로 노력하지 않고도 건축 작업에서 개성을 찾을 수 있는 가장 쉬운 방법 중하나가 될 수 있다고 생각했기 때문이다. 현장에서 타설될 때마다 야기되는 콘크리트의 불완전성은 컨텍스트가 동일한상황에서도 엄청난 다양성을 유발한다. 이러한 콘크리트의 본성 덕분에 아주 급진적인 노력이 없더라도 다양성을 창출할 수 있다. 거푸집을 구성하는 방식, 주조비율과 제조방식 등에 있어서 공정에 작은 변화만 주더라도 다른 결과물을 낼 수 있는 것이다.

박: 그래서인지 스몰프로젝츠의 프로젝트에 유독 콘크리트와 철이 많이 사용된다.

로우: 말레이시아에서 규모에 상관없이 거의 모든 프로젝트에서 가장 가성비가 좋은 재료가 철근콘크리트다. 이러한 재료선택이, 큰 가치에의 필요성보다는 경제성에 의해 결정되어 걱정되는 부분도 있다. 나는 콘크리트를 좀더 인간적으로 사용하려고 할 뿐이다. 마감재료, 구조적 기능의 필수적인 부분으로 사용하려고 한다.

박: 재료를 아주 섬세하게 사용하여 작은 부분까지 신경 쓴 점도 인상적이다. 디테일을 다룰 때 가장 중요하게 생각하는 점은 무엇인가?

로우: 나에게 디테일은 사물과 아이디어가 만나는 친밀하고 필수적인 결합이다. 나는 도시의 건물들 간의 관계가, 하나의 건물이 기존의 컨텍스트에서 두드러지게 표현되는 것보다도 더 중요하다고 생각하는데, 디테일도 다르지 않다. 디테일은 사물과 아이디어 사이의 보다 심오한 관계를 해결하고 발전시키기 위해 존재한다. 디테일이 유일하게 단점을 가질 때에는 그 자체의 아름다움만을 위해 존재하는 경우다. 그 외의 모든 다른 측면에서 장점을 가질 수 있다. 기후와 배수, 배수와 건물, 건물과 방, 방과 화장실, 화장실과 문, 문과 손잡이, 손잡이와 손등 여러 요소들 또는 여러 아이디어들의 관계의 맥락적 흐름은 모든 디테일에서 가장 중요하다. 그리고 이 모든 관계들이 잘 지켜질 때, 가장 정제된 아름다움을 표현할 수 있다고 생각한다. 디테일을 아름답게만 표현하려는 노력은 건축가가 추구할 수 있는 가장 불필요하고 퇴행적인 감성이다. 아쉽게도, 많은 건축가들이 이런 감성에 쉽게 빠지곤 한다.

박: 앞서 이야기 나눈 주재들이 실제 프로젝트에서는 어떻게 적용됐는지 궁금하다. 말레이시아 사라왁의 중앙 산맥에 위치한 바레오 마을에 예배당을 짓는 ‘부활 예배당’(2019)의 컨텍스트는 어떠했나?

로우: 지리적으로 접근이 쉽지 않은 곳에 위치하다 보니 재료 수급에 제약이 컸다. 비포장도로로 운반할 수 있는 시멘트, 모래, 철근만 사용하기로 결심했고, 투입되는 재료의 양 자체도 절약해야 했다. 지붕을 가장 경제적인 형태인 사각형으로 만들고, 모든 수직 부재를 10mm 철근을 세우는 것으로 해결했다. 벽 시공에도 비용이 많이 들었는데, 벽 자체가 예배당에 꼭 필요한 요소는 아니라 생략했다. 철근을 이용한 구조물이 충분한 전단력을 확보할 수 있도록 중앙 공간은 원형으로 계획했고, 3~4명 단위의 소규모 모임을 위해 모서리를 열린 공간으로 만들었다.

박: 건축은 장소의 역사적 맥락과 연결될 때 더욱 강력한 결과를 만들어낸다. 창작의 단계에서 이전의 형식으로부터 자유로워지는 것이 쉽지만은 않았을 텐데, 새로운 형식과 공간을 찾아가는 과정은 당신에게 어떤 의미가 있었나?

로우: 마을 중심부에 있는 지역 교회는 최소한의 콘크리트 기둥과 보를 구조로 하고, 거칠게 못을 박은 목재와 금속 골판 지붕이 얹어진, 이음새를 만드는 데 전혀 노력을 기울이지 않은 건물이었다. 교회 건물이었지만 학교 행사부터 마을 회의, 심지어는 저장과 보관에 이르기까지 다목적 홀과 다를 바 없는 대접을 받았다. 숭배를 목적으로 한 건축물의 전례가 없었기 때문에 역사적 맥락이 그리 많지 않았다. 내가 발견한 유일한 문화적 혹은 사회적 컨텍스트는 마을의 거의 모든 구성원들이 목재로 자신들의 집을 지었지만, 공공이 함께 사용하는 건물에서는 집에 비해 노력이 부족했다는 사실이다. 농촌지역에서 공동체 의식과 유대감이 더 깊다고 생각했던 것과 반대되는, 꽤나 흥미로운 발견이었다.

박: 사람들에게 건축의 형식은 어떤 의미를 가진다고 생각하는가?

로우: 사회가 건축을 이해할 때 피상적인 아름다움만 이야기하곤 한다. 사람들 사이에 맺어질 수 있는 어떤 심오한 관계보다 말이다. 심지어 건축가도 그런 경우가 있다. 이번 프로젝트의 경우에는 바레오 마을의 정착에 대한 건축적 포부, 미학과 무관하지 않은 실용성, 용도, 생존의 문제를 지향하는 것이 아닌가 하는 생각이 든다. 재료 선택은 아침 공기와 같이 흔하고 일상 같았더라도 예배당은 그들에게 미적으로 놀라움을 안겨주었을 것이다.

박: 조건과 환경이 쉽지 않았음에도 불구하고 시간과 노력을 기울여 품위 있는 결과가 나왔다고 생각한다. 시공에서 어려움은 없었는가?

로우: 품위라는 단어가 이렇게 쓰여도 되는지 모르겠다. (웃음) 공사에 시간이 아주 많이 걸리진 않았다. 공사에 참여한 사람이 적고 자재 배송 지연으로 단지 예상했던 시간보다 오래 걸렸을 뿐이다. 바레오로 가는 도로에 산사태가 일어나서 자재 배송을 기다렸던 어려움은 있었다. 그리고 바레오마을 사람들이 많은 노력을 기울였다. 부활 예배당 부지의 정원을 가꾸기 위해 언덕 꼭대기 전체를 다듬고 식재를 심고 정리했다.

박: 자연을 거스르지 않고 바람과 빛과 대지를 받아들이며 건축하는 방식에서 당신의 감각이 전달된다.

로우: 예배당을 이용하는 커뮤니티가 그런 느낌을 받기를 바란다. 이곳은 매주 36명 정도의 큰 모임과 개인 또는 매우 작은 모임들이 매일 진행된다고 한다. 만약 이 프로젝트가 아주 큰 공동체 교회를 위한 것이었다면 전혀 다른 디자인이 나왔을 것이다.

박: 또 궁금했던 프로젝트는 태국남부에 위치한 대규모 집합주택 ‘윈드쉘 나라티왓’(2019) 이다. 다수의 가구가 모여 사는 형식이라 각 집들 간의 관계를 고민하며 설계했을 것 같다.

로우: 프로젝트의 타깃은 부유층으로 다른 사회 구성원보다 프라이버시를 우선시할 것이라 예상했다. 여기에 사교와 교류의 기회가 보편적으로 주어지는 것이 아니라 선택적으로 제공되도록 했다. 예를 들어, 필요에 따라 쉽게 제거할 수 있도록 설계된 벽을 통해 이웃 간의 만남이 이루어진다. 그렇지만 풀장, 에어로빅과 웨이트를 위한 파빌리온, 요가실, 커뮤니티 주방 겸 식사공간, 바비큐를 위한 공유 가든 등 다양한 시설이 있는 옥상에서 이웃끼리의 상호작용이 가장 활발하게 일어날 거다. 지상 1층에도 라운지, 도서관, 넓은 정원과 연결된 공유 공간이 곳곳에 있어서 개인 공간이 아님에도 불구하고 ‘내 집에 왔다’는 느낌이 있을 거라 생각한다.

박: 윈드쉘 나라티왓에는 기후와 환경에 대한 고민도 드러난다. 공기의 흐름, 빛의 유입 등 중요하게 생각한 환경은 무엇이었나?

로우: 환기 문제는 수십 년 동안 논의되어 왔지만, 주로 주거지와 저층건물에 관해서만 논의되었다. 커다란 변화를 불러일으킬 만한, 패러다임을 흔들 만한 큰 변화가 있지는 않았다. 윈드쉘 나라티왓은 몬순기후 지역에 위치한 50층규모의 건물에서 환기 문제를 해결하기 위한 아이디어가 다뤄진 첫 번째 경우라는 점에서 그 의미가 컸다. 어쩔 때는 궂은 날씨에 바람이 심하고, 또 때로는 기후가 정체되는 현상이 예측 불가능하게 찾아오는 곳이었다. 파악해야 할 컨텍스트가 너무나도 많았고, 심지어 그곳에 떨어지는 빛조차 내가 알던 것과는 달랐다. 그랬기에 프로젝트 처음부터 태국 전통 주거 건축이 어떻게 강한 빛, 눈부심, 그림자의 대비를 다뤄왔는지를 살펴봤다. 방콕의 오래된 목조 주택은 내외부공간의 온도, 빛 그림자를 극명하게 대비하고 있었는데, 이는 오늘날 방콕의 스카이라인을 형성하는 전형적인 주거용 고층빌딩에서는 찾아볼 수 없는, 이제는 사라진 문화적 감수성이다. 자연 채광, 바람흐름 등에 대해 새로 경험하고, 배우고 발견하고 실수하고 해결해가는 과정을 겪었다.

박: 윈드쉘 나라티왓을 설명해 놓은 글을 보면, 내용이나 관점에 있어서 지극히 주거를 상품으로 바라본 시선이 느껴졌다. 주거를 재화로 바라보는 것에 대해 어떻게 생각하는가?

로우: 이 프로젝트는 클라이언트가 방콕 살라댕 지역에 있는 고급 펜트하우스보다 더 좋은 집을 찾는 것으로 시작됐다. 그는 전세계 어느 도시에서나 볼 수 있는, 세련되지만 전형적인 커튼 월 펜트하우스를 몹시 싫어했다. 그렇다고 정원이 딸린 단독주택을 짓기 위해 도심지에 막대한 돈을 쓰고 싶지는 않았다. 그래서 클라이언트 자신이 살고 싶은 단독주택을 고층으로 짓는다면 다른 사람들도 좋아할 것이라 생각하며, 자신의 집이 들어설 한 개 층의 공간을 다른 층의 판매 수익으로 충당하고자 했다. 이 프로젝트는 일반적인 2층 규모의 전원 주택이 갖춘 여러 조건들로부터 아이디어를 얻어 진행된 것이기에 ‘상품’처럼 보일 수밖에 없다. 글로벌비즈니스에서 상업적이고 투기적인 측면과 관련하여, 클라이언트와 나의 이해가 일치했기 때문에 이 프로젝트를 진행할 수 있었다. 단지 수익을 내는 데만 초점을 맞추지 않고 다양한방식으로 주거 환경을 개선하기 위해 설계했고 좋은 결과가 나왔다고 생각한다.

박: 집이 지나치게 상품화되면 여러 사회적 문제가 일어난다. 현재 한국은 고독사, 충간소음, 이웃의 부재, 물리적 접점의 문제 등을 겪고 있는데, 방콕과 말레이시아에서 프로젝트를 진행하고 있는 당신은 이러한 상황에 대해 어떻게 생각하는지 궁금하다.

로우: 나는 오늘날 우리 사회에서 사회적 매개가 부족한 이유가 건축보다는 사회경제적 문제와 연관된다고 생각한다. 전 세계적으로 지역사회와 사회적 상호작용이 가장 많은 동네는 빈민가와 도시의 빈곤한정착촌이다. 그리고 이러한 동네의 주거시설은 거주자들이 부와 재산을 조금씩 더 축적해가는 과정에 있어서 점차 사라지고 ‘보호'된다. 주거시설이 근본적으로 공유공간과 사적 공간사이의 균형이라는 사실은 종종 잊혀진다. 그러나 부가 일정한 임계점을 넘어서면, 공유 공간과 사적 공간의 균형을 맞추려는 인간의 욕구에서 벗어나 축적된 부를 보호하는 쪽으로 다시 한번 근본적인 변화를 겪는다. 이는 부유한동네에서 커뮤니티 시설, 공유공간이 점점 부족해지는 현실과 관련 있다. 건축이 상품화되거나 비판적 형태를 가지는 순간은 앞선 일들이 모두발생한 이후로, 그 시점에는 사회경제적 편견에 반응하는 것밖에 할 수 있는 게 없다. 하지만 빈민가와 불법 거주자정착지에서는 그렇게 큰문제가 되지 않는다. 그곳의 구성원들이 ‘사적’이고 ‘방어 가능한' 공간을 누릴 만큼 충분히 부가 축적되면 치안이 좋은 중상위층동네로 이동하기 때문에 빈민가, 불법 거주자정착지는 특정수준을 넘어서는 큰 변화가 없다. 하지만 사람들의 소득과 사회적 지위는 점진적으로 그리고 지속적으로 높아질 것이기에, 이웃 간의 교류와 상호작용이 전체적으로 점점 더 옅어지는건 아닐까 하는 걱정이 든다.

SMALL PROJECTS_ Kevin Mark Low

ON THE BORDER BETWEEN ART AND CAPITAL

Kevin Mark Low received his

BArch in University of Oregon in 1988 and M. S. Arch in MIT in 1991. He

established small projects in 2002 based in Malaysia and has worked various

projects in Malaysia, Thailand, and other countries. He has been professionally

involved in writing, environmental sculpture, illustrating, teaching, and

copyrighting.

Introduced here are small

projects, a team based in Malaysia's capital city, Kuala Lumpur. The principal

of small projects, Kevin Mark Low, studied architecture and fine art at the

University of Oregon and MIT, before returning to Malaysia to work for GDP

Architects for 11 years before establishing small projects in 2002. Today, 20

years after he opened the studio, he continues to take on design projects of

every scale, from mailboxes to architectural projects, while also contemplating

key architectural theories in his writing. Let's immerse ourselves in the

thinking embedded in his writing and his works.

Park Changhyun (Park): I've noticed the 'commentary' category on the small projects' website. This tab leads to a curated list of essays on architectural ideas, the first being 'context'. You've noted that 'Every single thing in existence is shrink wrapped in its unique dense weave of relationships that we call its context'. What is an architectural context more specifically?

Kevin Mark Low (Low): Architectural context is, at a fundamental level, a site's geographical properties, the regulations it abides by, the neighboring buildings, and the surrounding environment, to name a few. I always begin research of a specific context by observing the people and the tangible activities and relationships in and around any specific site. I attempt to study them as critically and thoroughly as possible before attempting to understand the tangible outcomes or physical expression of these contextual relationships in the built form. I then try to understand the problems or issues that are unique to that context. I proceed by forming a constant dialogue between questions and answers concerning the specific and the abstract, the tangible and the intangible, to hold any understanding between the two aspects of a context in tension.

Park: How do you balance the many kinds of

context understood in architecture; background, design preferences, among

others? Are there instances in which your personal context takes precedent over

a project context?

Low: My responsibility is less towards balance than towards discovering relevant questions that address the unique relationships which already characterize a specific context. All my decisions thereafter are guided by the relevance my solution has when answering the issues or problems specific to the context of the project. One naturally arrives at balance when discovering and working with the appropriate questions.

Park: I also very much enjoyed the essay on 'dog concrete' in the 'commentary' category. I agreed with your suggestion that 'Concrete can be as distinct and variable, one pour to the next, as the races of the human species'. Concrete varies depending on the country it was formed, and how the architect uses said material. What are the qualities of concrete and the advantages you hope to emphasize?

Low: I wrote almost twenty years ago about the nature of concrete as born from the genetic code of its formwork and its unique mix from country to country. I believe it to be one of the easiest ways of locating personality in a particular work of architecture. The imperfections of poured concrete from one project to another already provides tremendous variety in character, even within the same specific context. These characteristics provide diversity within the project without any excessive effort. Just a small change in the process, to the formwork or sand mix, can create varied results.

Park: It seems like this may be the reason why small projects' work uses concrete and steel so often?

Low: For almost all projects in Malaysia, regardless of scale, reinforced concrete is the most cost-effective material to use. I am afraid my choices have been determined more by economy than a deeper consideration of critical worth. I try to use concrete in a more humanizing fashion, as a material of finish or an integral part of its structural function.

Park: I appreciate your meticulous use of materials even in the smaller moments. What is your primary concern when working with details?

Low: Details for me are simply the intimate and vital junctions where things and ideas meet. I argue that the relationships between buildings in any city are more important than a statement made by a single building in speaking louder than its pre-existing context: details are no different. They exist to resolve and develop more profound relationships between things and ideas. A detail has failed only if it exists for its own aesthetic impression and nothing more. A detail is an advantage in every other way because it provides a contextual flow of relationships, be it between climate and drainage, drainage, and the building, building and room, room and toilet, toilet and door, door and handle, or handle to hand. And, when all these relationships are attended to well, the detail will simply express the beauty of the relationships it had considered. The effort put into making a detail look beautiful in and of itself is the most unnecessary and regressive sensibility any architect can pursue. Unfortunately, it is also a very common pursuit in the profession.

Park: I'm curious how these themes have

been applied in your projects. What was the context behind the Chapel Project

(2019), located in the middle of a mountain in Bareo, Sarawak in Malaysia?

Low: Almost everything revolved around budgeting for the quantity of material used due to these difficult geographical conditions. We opted only for materials transportable via the dirt road, cement, sand, and reinforced bar, while also minimizing the quantities of the materials themselves. The roof would be made to fit an economical orthogonal square, and all vertical support members would be built with 10mm reinforced bars. Since walls cut into our spiraling expenses and were deemed unnecessary in the chapel, they were omitted. The central gathering space was inscribed as a circle to develop better lateral support for the structure and the corners were left open for a gathering of smaller groups of three to four people.

Park: Architecture produces more profound results when it connects to its historical context. Can you outline the process behind finding a new structure and space, as they must be difficult to liberate from existing formal qualities?

Low: The community church in their town center was constructed very economically with minimal concrete columns and beams, a roof of crudely y bolted and nailed timber, and walls of metal siding, with little to no effort at all put into the crafting of the joints. As a rural settlement, the structure was treated no differently from a multi-purpose hall to serve anything from a school event to a town meeting or perhaps even for use as general storage. Not having much of a precedent for their purposes of dedicated worship, there was not much of historical context to draw from. The only sense of cultural or social context I discovered came from the fact that almost every member of the community built their own residences out of timber, but all their shared community structures lacked the same pride of effort as their own personal dwellings. It was an odd discovery because one would want to believe that rural settlements have a deeper sense of community.

Park: So, what do you think is the primary value of form in architecture for people?

Low: Society, including architects, largely only understands architecture in relation to superficial beauty, rather than to the more profound relationships that can be forged between people. In the case of the architecture aspirations regarding the settlement of Bareo, I suspect that these are more directed at issues of practicality, use, and survival, rather than anything having to do with architectural ambitions or aesthetic potential. Although the choice of materials is as common and 'everyday' to them as their morning mountain air, perhaps the chapel was an aesthetic surprise.

Park: Despite the harsh conditions, the time and effort allotted produced a dignified result. Were there any difficulties during construction?

Low: I am not sure if dignity is the right word! (laugh) The construction was not actually time-consuming. It only took longer than it could have because of the limited number of people involved in its construction and the delays in material delivery. There certainly were difficulties in waiting for delivery of the materials because of the landslide damage to the main trunk road to Bareo. Although, the people of Bareo provided a lot of assistance. They planted, trimmed, and cleared the entire hilltop garden to the simple landscape plan I developed for the project.

Park: The architectural methodology used was to construct in harmony with wind, light, and the landscape, and not against the natural elements-this reveals your sensibilities.

Low: I hope this is how the community feels when using the chapel. From what I have heard, it is used each week by larger gatherings of about 36, and by individuals or very small groups every day. It would have been a different design if the project had been for a full community church.

Park: Another project I want to discuss is the Windshell Naradhiwas (2019), a large apartment complex located in southern Thailand. As it is a multiunit model, you must have considered the relationships between each house?

Low: It was felt that the target market of the project, the wealthy, would prioritize privacy over all else, for which opportunities for sociability were provided as options rather than standards. For instance, opportunities for socializing have been created by way of walls that have been designed to be easily removed if so desired. However, the greatest degree of interaction between the neighbors would be on the rooftop where the shared facilities of a lap pool, the aerobics and weights pavilion, a yoga room, a community kitchen/dining area, and a community garden for barbeques are located. The ground level also features what is called a shared living room, a large space with a library and multiple lounges that open to the ample garden, such that the arrival home need not have to be only upon entry into one's own upper floor.

Park: The consideration of climate conditions is also evident in Windshell Naradhiwas. What environmental factors such as airflow and light were important in the formation of the project?

Low: The issues of cross ventilation have been discussed multiple times across the decades, but primarily in relation to residences and low-rise typology and not always in terms of the greater effect and ultimate changes to dominant paradigms. What was different and vital for the Windshell Naradhiwas was that it would be first time such ideas would be addressed in a fifty-story tower in the monsoon tropics, with extreme wind loads during inclement weather and very still air during certain times of the day in the unpredictable transition months. There were so many contextual unknowns to deal with, but the quality of light was not one of them. I had known that the dwellings would be configured as a return to the traditional Thai home, particularly in relation to the strong sun rays and the glare of a typical Bangkok day. The cultural sensibilities of internal coolness, light, and deep shadows in the old timber houses were nowhere to be found in the typical residential high rises of Bangkok. It was an experience of learning anew, discovery, and considering the typical mistakes when designing to contend with natural elements such as light and wind.

Park: Reading the description of the project gives an insight into the notion that you may view it as commodity. What are your thoughts on looking at houses as commercial products?

Low: The project took shape as the client was absorbed in looking for a better place to live than his current upmarket penthouse in the Saladaeng neighborhood. He disliked the fashionable but typical glass curtain-walled penthouses found all over metropolitan centers of iconic global cities intensely but did not wish to spend the stratospheric amounts of money required for downtown land to build a house with a garden. So, he desired to build the sort of high rise dwelling that he knew others would also appreciate, and in doing so, afford an entire floor in the project for his own home from its profits. So, the project was seen to be less of 'product' as such, than an exploration of ideas for everything that could be found in a two-story house with a garden. In relation to the commercial and the speculative aspects of housing development in the global industry, I agreed to be involved in this project because the client aligned with my understanding of the problems in the current paradigm conceiving of a diverse and balanced environment for habitation rather than merely focusing on making profit.

Park: The over-commodification of housing presents several social issues. Korea currently faces the problems of solitude, noise between floors, absence and distancing of neighbors and physical contact, and various other social complications. What do you think about this phenomenon as someone who currently has ongoing projects in Bangkok and Malaysia?

Low: I think the problems regarding the lack of social agency in our communities today is less to do with architecture than with socioeconomics. Neighborhoods globally with the greatest amount of community and social interaction are slums and impoverished urban settlements. Even certain dwellings in these communities become gradually more removed and 'protected' as their occupants accumulate a little more wealth and possessions. It is often forgotten that one of the fundamental needs of any dwelling is the balance between shared and private space. But to surpass a certain threshold of accumulated wealth, the equation again undergoes a fundamental shift, from the human need for good balance of shared to private space, to that of protecting the wealth one has accumulated. This is the root of the issue, regarding the increasing lack of community, neighborliness, civic and shared domains, in any specific residential district. Architecture, either in commodified or critical form, merely responds thereafter to this socio-economic bias. It is not as much of a problem in the slums or squatter settlements, because the moment a member of such a community has accumulated sufficiently to afford more 'private' and 'defensible' space, they move to low/middle class neighborhoods of relatively greater perceived security, leaving the slum relatively unchanged beyond a certain point. But in neighborhoods from low/middle to upper class incomes and social standing, the path to upgrade and ever heightened 'removal' begins its gradual but unstoppable journey thereafter, to less and less neighborhood interaction and connection.